Cilicia is the ancient Roman name for the southeastern region of Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey). It is referenced in the biblical books of Acts and Galatians, was the birthplace of Saint Paul, and the site of his early evangelical missions. The territory was first inhabited in the Neolithic Period c. 8th millennium BCE.

It was under Hittite control by the 2nd millennium BCE before passing to the Assyrians, gaining its independence after the fall of the Assyrian Empire in 612 BCE, and was then taken by the Persians before the conquest of Alexander the Great in 333 BCE. After Alexander, the region became Hellenized and politically aligned with Syria which is why some major Cilician cities such as Tarsus are often identified as Syrian in ancient texts.

After Alexander's death, the region was divided between the Ptolemaic and Seleucid empires. As the Seleucids began to lose power and influence over their part of the territory c. 110 BCE, the famous Cilician pirates emerged to fill the vacuum and exerted ever increasing control until c. 78-74 BCE when Rome intervened, conquering western Cilicia.

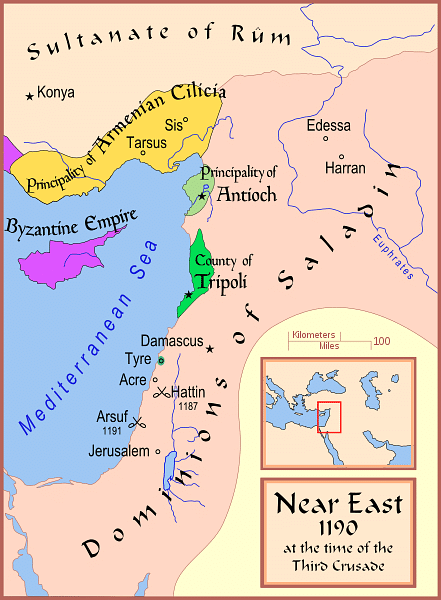

Pompey the Great defeated and resettled the Cilician pirates by 67 BCE, and the region remained a province of the Roman Republic, Roman Empire, and Byzantine Empire until the early 8th century CE when it was taken by invading Muslim forces. The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia flourished in the region between 1080-1375 CE before it fell to the Mamluks and was later incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1453 CE.

Because of its geography and location, Cilicia was among the most important regions of the classical world. The Cilician Gates, the only pass through the Taurus Mountains between the plains of Cilicia and the Anatolian Plateau, featured regularly in numerous military campaigns and, according to the Bible, was also used by Saint Paul and Barnabas on their evangelical missions in Asia Minor. The contributions to world culture of the native Cilicians and later Armenians encompass innovations in a number of disciplines including masonry, agriculture, and theology, most notably Christian theology as exemplified in the works of Saint Paul.

Early History & the Hittites

From the earliest mention in historical records, Cilicia has been referenced as comprising two interconnected regions: a fertile plain and the rugged mountains. In the Roman period, these were known as Cilicia Pedias (“smooth Cilicia” of the plains toward the Mediterranean Sea) and Cilicia Trachea (“rough Cilicia” of the foothills of the Taurus Mountains down to the rocky shore and inlets of the sea). Earlier references note the geological differences of the region by other names with the same connotation of “flat and fertile” and “rough and rugged”.

Sometime between 2700-2400 BCE, a people known as the Hatti either migrated into upper Anatolia or were natives of the region who only began making their presence known to the historical record at that time. Simultaneously or shortly afterward, a people known as the Luwians enter the record, but little is known of them except for their language which was related to but distinct from Hittite. The Hatti were an agrarian people who spoke a language called Hattic but wrote using Mesopotamian cuneiform (as did the Hittites). They established their central city, Hattusa, north of Cilicia in c. 2500 BCE and were a powerful force in the region, able to repulse invasion by the formidable Sargon of Akkad (also known as Sargon the Great, r. 2334-2279 BCE) who, failing to take Hattusa, claimed the southern coast line of Cilicia.

Cilicia was held, loosely, by the Akkadian Empire until its collapse c. 2083 BCE at which time the Hatti were able to completely reassert their control (although it is likely they had already done so long before). The Hatti controlled the ports along Cilicia's coast until the Hittite king Anitta of the Kingdom of Kussara invaded in 1700 BCE, destroyed Hattusa and established the so-called Old Hittite Kingdom (1700-1500 BCE). Still, some political autonomy seems to have survived as evidenced by a series of kings, beginning with Isputahsu (c. 15th century BCE), entering into treaties with the Hittites and Mitanni.

Under the Hittites

Between 1500-1400 BCE, the Old Kingdom declined but a new Hittite political entity was then established which is now known as the New Kingdom or the Hittite Empire (1400-1200 BCE). Any semblance of an autonomous Cilicia vanished as it became a vassal state of the Hittites. The greatest Hittite king of this period was Suppiluliuma I (r. c. 1344-1322 BCE) who expanded his territory and improved the kingdom's infrastructure. The city of Tarsus, a settlement already ancient by this time, was given its name by the Hittites. It was previously known as Tarsisi by the Akkadians, but the Hittites changed it to Tarsa in honor of one of their gods. The neighboring city of Adana (known as Uru Adaniyya) was also improved upon at this time.

Cilicia was known as Kizzuwatna (also given as Kizzuwadna) under the Hittites. Tarsa was the capital city and Suppiluliuma I, through a series of campaigns and shrewd manipulations, consolidated Hittite control of a vast region stretching across Anatolia, up into Mesopotamia, and down toward Egypt. Suppiluliuma I died of the plague in 1322 BCE and was succeeded by his son Mursilli II (r. 1321-1295 BCE) who continued his father's policies. His successor, Muwatalli II (r. 1295-1272 BCE), did the same and is best known for his engagement with Ramesses II of Egypt at the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE. At this time, the Hittite Empire was among the most powerful of the ancient world, but the Assyrians were growing stronger and finally challenged Hittite authority, defeating them at the Battle of Nihriya c. 1245 BCE. After this engagement, Hittite power began to wane, and the empire's fall was hastened by the arrival of the Sea Peoples who harassed the Mediterranean region c. 1276-1178 BCE.

The Sea Peoples & Assyrians

The identity of the Sea Peoples is still debated, and even the name they may have called themselves is unknown. “Sea Peoples” is a modern designation coined in c. 1881 by the French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero because ancient inscriptions describe them as coming “from the sea”. Various scholars have suggested they were Etruscans, Trojans, Myceneans, Libyans, or Minoans, or a coalition of some or all, but most scholars either include or define them primarily as Philistines.

The Sea Peoples are best known from the inscriptions of the Egyptian pharaohs Ramesses II (r. 1279-1213 BCE), Merenptah (r. 1213-1203 BCE), and Ramesses III (r. 1186-1155 BCE), and all three describe them as a coalition which came from the sea, struck suddenly, and caused severe damage. The scholar William H. Stiebing Jr. claims that they may have been Cilicians as one of the ethnicities included in ancient descriptions is the Danuna whom Stiebing claims were most likely from the city of Adana (224). If so, the Danuna could be considered early Cilician pirates. The Sea Peoples destabilized the region and toppled the already weakened Hittite Empire, eventually allowing the Assyrians to take the region with relative ease.

Under the Assyrians, the eastern fertile plains of Cilicia were called Qu'e, and the western region Hilikku, which provided the basis for the later Greek name Kilikia which was then rendered as Cilicia. The Assyrian king Tiglath Pileser III (r. 745-727 BCE) established the capital at Adana through a governorship but, as with the Akkadian Empire, the Assyrian hold over Cilicia was never firm, and it slipped from their grasp shortly after the death of Sargon II in 705 BCE.

Around this time, the king Muksa (better known as Mopsus, 8th century BCE) ruled from Adana but the region would not remain independent for long as Qu'e was retaken by the Assyrian king Esarhaddon (r. 681-669 BCE) who left Hilikku to anyone who cared to live there. The Assyrians retained control of the region until 612 BCE when their empire collapsed under the invading coalition of Babylonians and Medes.

The Persians & Alexander the Great

Hilikku at this time asserted itself as an independent state governed by a monarch known as a syennesis which was either a throne name or title. The capital was established at Tarsus, and trade flourished between the region, now regularly referenced as “Cilicia” by the Greeks, and other countries. C. 547 BCE, the Persian king Cyrus the Great invaded, adding Cilicia to his Achaemenid Empire. The syennesis at this time was a native of the region who served as a Persian satrap governing from Tarsus. This policy was changed after the rebellion of Cyrus the Younger in 401 BCE when the syennesis aligned himself with the rebel forces. The position was eliminated afterwards, and the satrap was appointed by the Persian king.

The Satrapy of Cilicia generated significant income for the Persian Empire. The satrap presided over a hierarchy with landed nobles at the top, followed by priests of the Zoroastrian religion, government bureaucrats, merchants, and the lower class of artisans and farmers. Hilikku remained semi-independent as compared with the lowlands of Qu'e most likely because the terrain was too difficult to control through military campaigns.

The old religion of the Hatti, centered on a Mother Goddess, was still observed in Hilikku, the deity now taking on the name Artemis Perasia or Cybele whose sacred site was at Castabala. The people of Qu'e may have also honored this same goddess but were officially Zoroastrian, the state religion of the Persian Empire, and there was also a significant community of Jews throughout Qu'e. There is evidence of armed conflict between the highlands and lowlands throughout the 4th century BCE, most likely over land rights along the border.

In 333 BCE, Alexander the Great seized the Cilician Gates in a surprise attack and struck quickly at Tarsus, taking the city. He installed his own satrap, Balacrus, to oversee administration while he led his army against the people of Hilikku but could not dislodge them. Before continuing on his campaigns elsewhere, Alexander ordered Balacrus to continue the action against the hill people, but he had no more success than Alexander had.

After Alexander's death in 323 BCE, Cilicia was included in the territories his generals fought over and finally divided between Ptolemy I Soter and Seleucus I Nicator. During this period, Cilicia became thoroughly Hellenized and Greek replaced the old language of Luwian. The plains of Qu'e continued their commerce with other nations as always, but the people of Hilikku appear in the historical record as thriving primarily from piracy. As the Seleucid Empire lost power beginning c. 110 BCE, political cohesion in Cilicia weakened. Tigranes the Great of Armenia (r. c. 95 - c. 56 BCE) took the eastern part of the region, allowing for Armenian settlement in Cilicia, at the same time the pirates of Hilikku were growing bolder.

The Cilician Pirates & Rome

The ships that plundered coastal cities and eventually disrupted trade are regularly referenced as manned by “Cilician pirates” but not all the pirates were native Cilicians. Hilikku's southern rocky coast offered a number of harbors and safe havens for pirates of any nationality and so Cilicia became closely associated with piracy. The rulers of both the Seleucid and Ptolemaic empires largely turned a blind eye to piracy because the Cilician pirates trafficked primarily in slaves which both required. Rome – who had taken Cilicia Pedias in 103 BCE – won the land after a campaign against pirates but, afterwards, regarded them as little more than a necessary nuisance for the same reason as the Seleucids and Ptolemies. The pirates of Cilicia, with no one seriously opposing them, grew more daring. They took Roman ships, raided the Roman port of Ostia, and hampered legitimate trade. Finally, Rome understood that the Cilician pirates would have to be dealt with.

In 75 BCE, a young Julius Caesar was kidnapped by pirates and held for ransom, a telling example of precisely how bold the Cilician pirates had become. The consul Publius Servilius Vatia (served 79 BCE) launched a campaign against the Isaurians of Cilicia between 78-74 BCE and conquered them (thus earning the surname Isauricus for his victory).

This did little to curb piracy in the Mediterranean, however, and so, in 67 BCE, Pompey the Great (l. 106-48 BCE) was tasked with taking care of the problem as part of his campaign against Mithridates VI (r. 120-63 BCE) who had enlisted the pirates in his war with Rome.

Pompey divided the Mediterranean into sections which could be more easily managed and appointed specific commanders to each. As the pirates in each district were defeated, the theoretical sections grew smaller until, by 66 BCE, Pompey had broken the power of the Cilician pirates (although he had not eradicated the problem completely). He then settled the former pirates in central Cilicia, creating prosperous communities which contributed to the stability of the region. Pompey divided Cilicia into six districts and, at this time, Cilicia Pedias became Cilicia Campestris and Cilicia Trachea was Cilicia Aspera.

Roman Cilicia

These two were both under Roman administration by 64 BCE although, as usual, Cilicia Aspera was largely left to itself. Under Julius Caesar, the province was reorganized in 47 BCE with different districting. It was joined to Syria as Syria-Cilicia Phoenice in 27 BCE, and the whole province, including Cilicia Aspera, was united under Vespasian in 72 CE. The Cilician pirates settled by Pompey practiced Mithraism and most likely introduced the religion to the Roman army, through which it was popularized in Rome and in other provinces. Zoroastrianism was still observed in Cilicia as was Judaism which attracted a number of sympathizers.

In order to fully embrace Judaism, however, one needed to accept the whole of the Law of Moses with stipulations in diet and custom which would have separated a convert from family, friends, and other social circles. The Jewish rituals and the concept of a single, all-powerful God were attractive to a number of Greeks living in Cilicia who appear in records as “reverent ones” – people who observed certain Jewish rituals and honored the Jewish God but remained Gentiles.

Scholar F. E. Peters notes how clubs of “Sabbatists” formed in Cilicia who celebrated the Jewish sabbath and kept other rituals but retained their Gentile identity (307). This movement would prove especially important in the early years of Christianity when Saint Paul (formerly Saul of Tarsus) initiated his evangelical missions in the region and found a receptive audience. Christianity offered precisely what the Sabbatists were interested in: Jewish theology and ritual without adherence to Mosaic Law. Christianity, naturally, found a home more easily in Cilicia than in other provinces.

Under the Romans, Cilicia continued to export the kinds of goods it always had: wine, cereals, beans, fish, tents, and cilicium – a rough cloth of goat hair used in tent-making – which, under the name cilice, would become popular among Christians when worn as a shirt while doing penance. Cilicium, in fact, would continue in this use up through the European Middle Ages, usually referenced as a “hair shirt”.

Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia

When the Western Roman Empire fell in 476 CE, Cilicia continued as part of the eastern, or Byzantine, Empire. By this time, the two primary districts were known as Cilicia Prima and Cilicia Secunda (Cilicia One and Cilicia Two). The churches established by Saint Paul flourished and the Byzantine Empire championed Christianity against the emerging religion of Islam in the 7th century CE. Cilicia was conquered by the Muslims in c. 700 CE but was retaken by the Byzantines in 965 CE under their emperor Nikephoros II Phokas (r. 963-969 CE). In time, the region attracted Armenian settlers, many of whom were already in the region since the time of Tigranes, who established their own communities and trade contacts as they steadily developed their own political identity.

In c. 1080 CE, the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia was founded and served as an important resource for European armies during the Crusades, especially the First Crusade (1096-1099 CE). The Armenians developed their rich culture further in Cilicia, perfecting Armenian architecture, art, and innovations in music and dance, among other contributions. The ruins of their impressive fortresses can still be visited in the present day, many on high slopes and constructed at seemingly impossible angles.

The Armenian kingdom continued to prosper until threatened by Muslim Mamluks. The Armenians called upon their former friends and allies in Europe for help in mounting another crusade to protect the kingdom but no help came and the Mamluks conquered the region in 1375 CE. After the Byzantine Empire fell in 1453 CE, the region was absorbed by the Ottoman Empire which held it until 1921 CE when, after World War I, it became part of the Republic of Turkey.

The people of ancient Cilicia are too often referenced by historians only as pirates or the conquered of other nations but were far more than either. They were well respected in antiquity as impressive masons, farmers, vintners, sailors, merchants, artisans, warriors, and theologians. Cilicia, in fact, has a far better claim to the title of birthplace of Christianity than anywhere else as Saint Paul was a native and some of the earliest Christian missionary efforts first flourished there. The Cilicians bore the conquest of empire after empire but, no matter who claimed to govern them, they prospered through adversity and continued to endure long after those empires had fallen.