Syria is a country located in the Middle East on the shore of the Mediterranean Sea and bordered, from the north down to the west, by Turkey, Iraq, Jordan, Israel, and Lebanon. It is one of the oldest inhabited regions in the world with archaeological finds dating the first human habitation at c. 700,000 years ago. The Dederiyeh Cave near Aleppo has produced a number of significant finds, such as bones, placing Neanderthal habitation in the region at that time and shows continual occupation of the site over a substantial period.

The first evidence of modern humans appears c. 100,000 years ago as evidenced by finds of human skeletons, ceramics, and crude tools. There seem to have been mass migrations throughout the region that impacted the various communities but, as there is no written record of the period, it is unknown why they happened if they did occur. These migrations are suggested by archaeological finds throughout the region showing significant changes in the manufacture of ceramics and tools found at various sites. These developments, however, could be just as easily explained by cultural exchange between tribes in a region or simply similar developments in the manufacturing process rather than large-scale migration. The historian Soden notes that,

Scholars have sought to deduce especially important developments, for example, folk migrations, from cultural changes which can be read in archaeological remains, particularly in ceramic materials…Yet there can be frequent and substantial changes in the ceramic style, even if no other people has come onto the scene. (13)

It is thought that climate change in the area c. 15,000 years ago may have influenced humans to abandon the hunter-gatherer lifestyle and initiate an agricultural one or that migrating tribes introduced agriculture to different regions. Soden writes, “We term 'prehistoric' those epochs in which nothing had yet been written down, without thereby assuming that events of great significance had not yet taken place” (13). The significance of the mass migration theory is that it explains how agriculture became so widespread in the region when it did but, again, this theory is far from proven. It is clear, however, that an agrarian civilization was already thriving in the region prior to the domestication of animals c. 10,000 BCE.

The Name & Early History

In its early written history, the region was known as Eber Nari ('across the river') by the Mesopotamians and included modern-day Syria, Lebanon, and Israel (collectively known as The Levant). Eber Nari is referenced in the biblical books of Ezra and Nehemiah as well as in reports by the scribes of Assyrian and Persian kings. The modern name of Syria is claimed by some scholars to have derived from Herodotus' habit of referring to the whole of Mesopotamia as 'Assyria' and, after the Assyrian Empire fell in 612 BCE, the western part continued to be called 'Assyria' until after the Seleucid Empire when it became known as 'Syria'. This theory has been contested by the claim that the name comes from Hebrew, and the people of the land were referred to as 'Siryons' by the Hebrews because of their soldiers' metal armor ('siryon' meaning armor, specifically chain mail, in Hebrew). There is also the theory that 'Syria' derives from the Siddonian name for Mount Hermon - 'Siryon' – which separated the regions of northern Eber Nari and southern Phoenicia (modern Lebanon, which Sidon was a part of), and it has also been suggested that the name comes from the Sumerian, 'Saria' which was their name for Mount Hermon. As the designations 'Siryon' and 'Saria' would not have been known to Herodotus, and as his Histories had such an enormous impact on later writers in antiquity, it is most likely that the modern name 'Syria' derives from 'Assyria' (which comes from the Akkadian 'Ashur' and designated the Assyrian's chief deity) and not from the Hebrew, Siddonian, or Sumerian words.

Early settlements in the area, such as Tell Brak, date back to at least 6000 BCE. It has long been understood that civilization began in southern Mesopotamia in the region of Sumer and then spread north. Excavations at Tell Brak, however, have challenged this view, and scholars are divided as to whether civilization actually began in the north or if there could have been simultaneous developments in both areas of Mesopotamia. The claim that, in the words of the scholar Samuel Noah Kramer, “history begins at Sumer” is still most widely accepted, however, owing to the certainty of the presence of the so-called Ubaid people in southern Mesopotamia prior to the rise of communities in the north such as Tell Brak. This debate will continue until more conclusive evidence of earlier development in the north is unearthed and, presently, both sides in the argument offer what seems to be conclusive proof for their respective claims. Until the discovery of Tell Brak (first excavated by Max Mallowan in 1937/1938 CE), there was no doubt regarding the origins of civilization in Mesopotamia, and it is certainly possible that future finds in the modern countries which were once Mesopotamia will help decide this point, although evidence for civilization beginning in Sumer seems far more conclusive at this point.

The two most important cities in ancient Syria were Mari and Ebla, both founded after the cities of Sumer (Mari in the 5th and Ebla in the 3rd millennium BCE) and both of which used Sumerian script, worshipped Sumerian deities, and dressed in Sumerian fashion. Both of these urban centers were repositories of vast cuneiform tablet collections, written in Akkadian and Sumerian, which recorded the history, daily life, and business transactions of the people and included personal letters. When Ebla was excavated in 1974 CE, the palace was found to have been burned and, as with Ashurbanipal's famous library at Nineveh, the fire baked the clay tablets and preserved them. At Mari, following its destruction by Hammurabi of Babylon in 1759 BCE, the tablets were buried under the rubble and remained intact until their discovery in 1930 CE. Together, the tablets of Mari and Ebla provided archaeologists with a relatively complete understanding of life in Mesopotamia in the 3rd millennium BCE.

Syria & the Empires of Mesopotamia

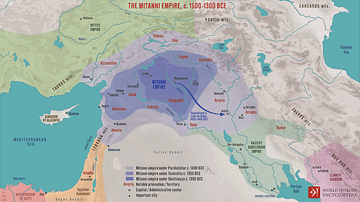

Both cities were founded c. 4000-3000 BCE and were important centers of trade and culture by 2500 BCE. Sargon the Great (2334-2279 BCE) conquered the region and absorbed it into his Akkadian Empire. Whether Sargon, his grandson Naram-Sin, or the Ebalites themselves first destroyed the cities during the Akkadian conquest is a matter of debate which has continued for some decades now but both cities sustained significant damage during the time of the empire of Akkad and rose again under the control of the Amorites after the Akkadian Empire had fallen in the second millennium BCE. It was at this time that Syria came to be known as the Land of Amurru (Amorites). The Amorites would continue to call the land their own and to make incursions into the rest of Mesopotamia throughout its history but the region of Syria would also continually be wrested from their control. Since it was recognized as an important trade region with ports on the Mediterranean, it was prized by a succession of Mesopotamian empires. The Hurrian Kingdom of Mittani (c. 1475-1275 BCE) first seized the area and built (or rebuilt) the city of Washukanni as their capital. They were conquered by the Hittites under the reign of the Hittite king Suppiluliuma I (1344-1322 BCE) who placed Hittite rulers on the Mitanni throne.

Egypt had long had trade relations with Syria (archaeological finds at Ebla substantiate trade with Egypt as early as 3000 BCE) and fought a number of battles with the Hittites for control of the region and access to trade routes and ports. Suppiluliuma I had taken Syria before the conquest of the Mitanni and, from his bases there, made incursions down the coast throughout the Levant, threatening Egypt's borders. As the Hittite and Egyptian forces were equal in strength, neither could gain the upper hand until Suppiluliuma I and his successor Mursilli II died, and the kings who came after them could not maintain the same level of control.

The famous Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE, between the Egyptians and the Hittites over the trade center of Kadesh in Syria, was a draw. Although both sides claimed victory, neither obtained their objective, and this was most likely noted by the other power growing in the region: the Assyrians. The Assyrian king Adad Nirari I (1307-1275 BCE) had already driven the Hittites from the region formerly held by the Mitanni and his successor, Tikulti-Ninurta I (1244-1208 BCE) decisively defeated the Hittite forces at the Battle of Nihriya c. 1245 BCE. The Amorites then tried to assert control after the fall of the Hittites and gained and lost ground to the Assyrians over the next few centuries until the Middle Assyrian Empire rose to power, conquered the region, and stabilized it. This political stability was upset by the invasions of the Sea Peoples and the Bronze Age Collapse c. 1200 BCE, and Mesopotamian regions changed hands with different invading forces (such as the Elamite conquest of Ur in 1750 BCE which ended the Sumerian culture). This instability in the region continued until the Assyrians gained supremacy with the rise of the Neo-Assyrian Empire under King Adad Nirari II (912-891 BCE). The Assyrians expanded their empire across the region, down through the Levant and, ultimately, controlled Egypt itself.

After the fall of the Assyrian Empire in 612 BCE, Babylon assumed control of the region and exerted control north and south of their city, conquering Syria and destroying Mari. The historian Paul Kriwaczek writes how, after Babylon's conquest of Assyria, “the western half of Assyria's domain was still called the province of Assyria – later, having lost its initial vowel, Syria. The Persian Empire retained the same name, as did Alexander's empire and its successor the Seleucid state, as well as the Roman Empire which was its inheritor” (207). At this time the Aramaeans were the majority in Syria and their alphabet, which had been adopted by the Assyrian king Tiglath Pileser III to replace Akkadian in the empire, provided the written history of the region. The Phoenicians, before this time, had occupied the coastal regions of Syria and their alphabet, which had merged with that of the Aramaeans (along with loan words from Akkadian), became the script inherited by the Greeks.

Syria & the Bible

Babylon held the region from 605-549 BCE until the Persian conquest and the rise of the Achaemenid Empire (549-330 BCE). Alexander the Great conquered Syria in 332 BCE and, after his death in 323 BCE, the Seleucid Empire ruled the region. The next big power was Parthia until, weakened by repeated attacks by the Scythians, their empire fell. Tigranes the Great (140-55 BCE) of the Kingdom of Armenia in Anatolia was welcomed by the people of Syria as a liberator in 83 BCE and held the land as part of his kingdom until Pompey the Great took Antioch in 64 BCE and annexed Syria as a Roman province. It was completely conquered by the Roman Empire in 115/116 CE. The Amorites, Aramaeans, and Assyrians made up most of the population at this time and had a significant impact on the religious and historical traditions of the Near East. The historian Kriwaczek, citing the work of the Assyriologist Professor Henry Saggs, writes:

Descendants of the Assyrian peasants would, as opportunity permitted, build new villages over the old cities and carried on with agricultural life, remembering traditions of the former cities. After seven or eight centuries and after various vicissitudes, these people became Christians. These Christians, and the Jewish communities scattered amongst them, not only kept alive the memory of their Assyrian predecessors but also combined them with traditions from the Bible. The Bible, indeed, came to be a powerful factor in keeping alive the memory of Assyria. (207-208)

The historian Bertrand Lafont, among others, has noted the “parallels that are sometimes evident between the content of the tablets at Mari and biblical sources” (Bottero, 140). Kriwaczek, Bottero, and many older scholars and historians since the 19th-century CE discovery of much of ancient Mesopotamia and the 20th century find of the tablets at Ebla have repeatedly written on the direct influence of Mesopotamian history on the biblical narratives so that, at this point, there is no doubt that popular stories such as the fall of man, Cain and Abel, the great flood, and many other tales from the Bible originated in Mesopotamian myths. There is also no doubt that the pattern of monotheism as illustrated in the Bible existed previously in Mesopotamia through worship of the god Ashur, and that this idea of a single, all-powerful, deity would be one reason behind the claim (which has been contested) that the Assyrians were the first to accept Christianity and set up a Christian kingdom: because they were already familiar with the idea of an omnipresent, transcendent god who could manifest himself on earth in another form. Kriwaczek clarifies this in writing:

That is not to say that the Hebrews borrowed the notion of a single omnipotent and omnipresent God from Assyrian predecessors. Just that their new theology was far from an utterly revolutionary and unprecedented religious movement. The Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition that began in the Holy Land was not a total break with the past, but grew out of religious ideas that had already taken hold of Late Bronze and Early Iron Age northern Mesopotamia, the world view of the Assyrian kingdom, which would spread its faith as well as its power right across western Asia over the course of the following centuries. (231)

This heritage was held by the people of Syria who, it is claimed, could have influenced depictions of kings, battles, and events as recorded in the Old Testament and even the vision of the risen god as given in the New Testament. Saul of Tarsus, who would later become the apostle Paul and then Saint Paul, was a Roman citizen of Tarsus in Syria who claimed to have seen a vision of Jesus while en route to Damascus (also in Syria). The first major center of Christendom rose in Syria, at Antioch, and the first evangelical missions were launched from that city. Scholars such as Hyam Maccoby (and, earlier, Heinrich Graetz in his History of the Jews) have suggested that the apostle Paul synthesized Judaism and Mesopotamian – particularly Assyrian – mystery religions to create the religion which became known as Christianity. If one accepts these claims, then Panbabylonism (the historical viewpoint that the Bible is derived from Mesopotamian sources) owes its existence to the people of Syria, who would have helped to spread Mesopotamian culture.

Rome, the Byzantine Empire, & Islam

Syria was an important province of the Roman Republic and, later the Roman Empire. Both Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great favored the region and, after the rise of the empire, it was considered one of the most essential regions owing to its trade routes and ports on the Mediterranean Sea. In the First Jewish-Roman War of 66-73 CE, Syrian troops played a decisive role at the Battle of Beth Horon (66 CE), where they were ambushed by Judean rebel forces and slaughtered. The Syrian warriors were highly regarded by the Romans for their skill, bravery, and effectiveness in battle, and the loss of a legion convinced Rome of the need to send the full force of the Roman military against the rebels of Judea. The rebellion was brutally put down by Titus in 73 CE with tremendous loss of life. Syrian infantry were also involved in putting down the Bar-Cochba Revolt in Judea (132-136 CE) after which the emperor Hadrian exiled the Jews from the region and renamed it Syria Palaestina after the traditional enemies of the Jewish people.

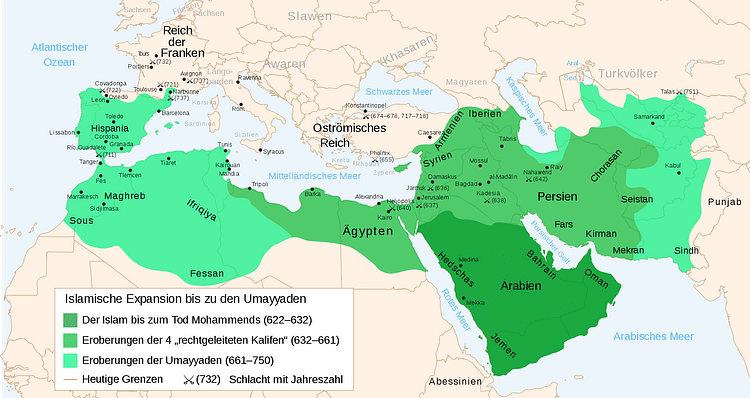

Three later emperors were Syrian by birth: Elagabalus (reigned 218-222 CE), Alexander Severus (reigned 222-235 CE), and Philip the Arab (244-249 CE). Emperor Julian (361-363 CE), the last non-Christian emperor of Rome, paid particular attention to Antioch as a Christian center and tried, unsuccessfully, to mollify religious strife between pagans and Christians in the region which he had, unwittingly, fostered. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Syria was part of the Eastern, or Byzantine, Empire and continued as an important center of trade and commerce. In the 7th century CE, Islam began to spread through the region through the Arab Conquests and, in 637 CE, the Muslims defeated the armies of the Byzantine Empire at the Battle of the Iron Bridge at the Orontes River in Syria. This proved to be the decisive battle between the Byzantines and the Muslims and, after the fall and capture of Antioch, Syria became absorbed into the Rashidun Caliphate.

The majority of the populace was at first relatively unaffected by the change in government from the Byzantines to the Muslims. The Muslim conquerors maintained a tolerance for other faiths and allowed the continued practice of Christianity. Non-Muslims were not allowed to serve in the Rashidun Army, however, and, as the army offered steady employment, a majority of the populace may have converted to Islam simply to procure jobs. This theory has been contested but there was a steady conversion of the majority of the population to Islam. The Islamic Empire spread rapidly throughout the region and Damascus was made the capital, resulting in unprecedented prosperity for the whole of Syria which, at that time, had been divided into four provinces for ease of governance. The Umayyad Dynasty was overthrown by another Muslim faction, the Abbasid, in 750 CE and the capital was at that time moved from Damascus to Baghdad which caused economic decline throughout the region. Arabic was proclaimed the official language of the region of Syria, and Aramaean and Greek fell out of use.

The new Muslim government was busied with affairs throughout the empire, and the cities of the region of Syria suffered deterioration. The Roman ruins and cities, still extant in the modern day, were abandoned as dams diverted water away from previously vital communities. The ancient region of Eber Nari had now become Muslim Syria, and the people would continue to suffer the invading forces of various warlords and political factions fighting for control of the region's resources over the next few centuries without regard for the impressive history of the land, the preservation of that history and those resources, or the population who lived there; a situation which continues to trouble the region, in varied form, even to the present day.