Paul was a follower of Jesus Christ who famously converted to Christianity on the road to Damascus after persecuting the very followers of the community that he joined. However, as we will see, Paul is better described as one of the founders of the religion rather than a convert to it. Scholars attribute seven books of the New Testament to Paul; he was an influential teacher and a missionary to much of Asia Minor and present-day Greece.

A Founder of Christianity

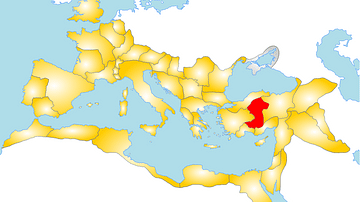

In the last century, scholars have come to appreciate Paul as the actual founder of the religious movement that would become Christianity. Paul was a Diaspora Jew, a member of the party of the Pharisees, who experienced a revelation of the resurrected Jesus. After this experience, he traveled widely throughout the eastern Roman Empire, spreading the “good news” that Jesus would soon return from heaven and usher in the reign of God (“the kingdom”). Paul was not establishing a new religion; he believed that his generation was the last before the end time when this age would be transformed. However, as time passed and Jesus did not return, the second century Church Fathers turned to Paul's writings to validate what would ultimately be the creation of Christian dogma. Thus, Paul could be viewed as the founder of Christianity as a separate religion apart from Judaism.

In Christian tradition, he is known as Paul of Tarsus, as this is where Luke says he was born (Acts 9:11). At the time, Tarsus was located in the province of Cilicia, now modern Turkey. However, Paul himself indicates that he was from the area of Damascus which was in Syria (see the letter to the Galatians). Luke has provided many of the standard elements in Paul's life, but most of these items stand in stark opposition to what Paul himself reveals in his letters. For instance, Luke claims that Paul grew up in Jerusalem, studying at the feet of many who would be considered the first rabbis of normative Judaism, and eventually becoming a member of the council, or the Sanhedrin. Paul himself says that he only visited Jerusalem twice, and even then his stay was a few days. What do we do about such contradictions?

On the one hand, Luke has a very obvious agenda in his presentation of Paul as someone who willingly obeys any dictates from Jerusalem, consulting them constantly on how he should run his “mission”. On the other hand, Paul has an agenda as well, claiming that no one human told him what to do, but that it was the resurrected Christ who gave him the game plan (see Galatians), and so he continually dismisses any influence from Jerusalem in his overall activities. In the final analysis, it is usually best to consult Paul's letters over Luke's version in terms of historicity when it comes to both Paul's motivation and his actual work.

Paul's Works

In the New Testament, we have 14 letters traditionally assigned to Paul, but the scholarly consensus now holds that of the 14, seven were actually written by Paul:

- 1 Thessalonians

- Galatians

- Philemon

- Philippians

- 1 & 2 Corinthians

- Romans

The others were most likely written by a disciple of Paul's, using his name to carry authority. We understand these letters to be circumstantial, meaning they were never intended as systematic theology or as treatises on Christianity. In other words, the letters are responses to particular problems and circumstances as they arose in various communities. They were not written as universal dictates to serve as Christian ideology but only came to have importance and significance over time.

Paul's Conversion

Paul was a Pharisee, and claims that when it came to “the Law,” he was more zealous and knew more about the law than anyone else. For the most part in his letters, the Law at issue was the Law of Moses. He was of the tribe of Benjamin (and thus Luke could use the prior name Saul, a quite famous Benjaminite name; name changes often go with a change of viewpoint in terms of a new person - Abram to Abraham, Jacob to Israel, Simon to Peter, etc.) He has also become the most famous convert in history. Being struck blind on the road to Damascus has become a metaphor for sudden enlightenment and conversion.

However, 'convert' is not the most accurate term to be applied to him. Conversion assumes changing from one kind of belief to another. There are two problems with this concept as applied to Paul:

- at the time, there was essentially no Christian religion for him to convert to

- Paul himself is ambiguous when it comes to understanding what he would have considered himself.

When he says “When among the gentiles, I acted as a gentile, and when among the Jews, I acted as Jew; I was all things to all men,” it does not help us resolve the question. In talking about what happened to Paul, it is probably better to say that he was called by God, in the tradition of the calling of prophets of ancient Israel.

In Galatians, Paul said he received a vision of the resurrected Jesus, who commissioned him to be the Apostle to the gentiles. This was crucial for Paul in terms of his authority. Everyone knew that he was never one of the inner circle, so a directive straight from Jesus was the way in which Paul argued that he had as much authority as the earlier Apostles. This is also crucially important in unraveling Paul's views of the Law of Moses when it comes to his recruitment area and something that should always be borne in mind when trying to analyze his views.

Paul's call to be the Apostle to the gentiles was shocking because, as he freely admits, he had previously persecuted the church of God. What a loaded sentence! Most scholars cannot agree on what this means. The first problem is with the word 'persecuted'. In Greek, this could mean anything from heckling to throwing eggs to physical abuse. He never really explains it, nor does he give any explanation as to why he did it. Luke says that he used to vote the death penalty for Christians in the Sanhedrin and then he obtained arrest warrants from the high priest to arrest Christians in Damascus (where he had his revelation). This is hyperbole on Luke's part; the high priest at the time had no such authority, especially in another province.

Paul as a Persecutor

Paul probably meted out what he himself received - the 39 lashes, a form of synagogue discipline. But this raises more questions. Synagogue councils had authority only upon the agreement of those in the community. In other words, Paul could have walked away from this, but he did not - again, does this indicate that he still saw himself as a Jew? And again, what did he receive the lashes for? What were Christians saying/doing that would lead to disciplinary action? Many theories have been offered over the centuries:

- Christians taught against the Law of Moses. This is true when it came to gentiles, but then gentiles were never expected to follow the Law anyway.

- Christians were stirring people up with messianic fervor. These were the decades leading up to the Jewish Revolt. Did synagogue authorities see such preaching as a threat to the peace of their community vis-à-vis Rome?

- Christians and Jews were in hard-fought competition for the souls of those gentiles who were hanging out at the synagogues and Jews saw the Christians as a threat to their recruitment areas. This one is patently false; Judaism was not a missionary religion.

- Paul, like John, contains high Christology. His experience of seeing Jesus in heaven means that Jesus was already deified in a sense for him. And he advocated worship of Jesus, which is probably the turning point between Jews and Christians. He repeats a hymn he had inherited in his letter to the Philippians:

5 In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus:

6 Who, being in very nature God,

did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage;

7 rather, he made himself nothing

by taking the very nature of a servant,

being made in human likeness.

8 And being found in appearance as a man,

he humbled himself

by becoming obedient to death—

even death on a cross!

9 Therefore God exalted him to the highest place

and gave him the name that is above every name,

10 that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow,

in heaven and on earth and under the earth,

11 and every tongue acknowledge that Jesus Christ is Lord,

to the glory of God the Father.

“That every knee should bow,” indicates worship. Hellenistic Judaism had incorporated a multitude of heavenly beings, with accompanying hierarchies (archangels, cherubim, seraphim, etc.), but no one ever advocated worshipping any of these beings - that was reserved for God alone. This is where Christians would begin the process of separating from the mother religion.

Paul & the Law

Paul's job, as he saw it, was to bring “the good news” to the gentiles. Almost everything he writes about the Law pertains to this. The Law of Moses was never understood to be applied to the gentiles in Israelite tradition, so gentiles need not be subject to circumcision, dietary laws, or Sabbath regulations. These three are the focus, as they are physical rituals that keep communities separated, and Paul sought to break down barriers between communities. Paul was adamant on the subject. One of the reasons is that it is probably what he experienced - he most likely observed some manifestation of the spirit take place, when gentiles were baptized (such as speaking in tongues, the room shaking, prophecy, etc.), and so he was convinced. If God chose to validate gentiles in this way, how could they not be included in the kingdom?

But Paul has a problem. He was a Pharisee. The Law held great meaning for him. How could God have created the Law, but then not apply it universally? This is where it gets a little sticky - he can never say that the Law is not good, and so he defends it, but at the same time, it does not apply to gentiles. And in doing so, he sometimes paints himself into a corner and provides centuries of scholarly books and commentaries on this very subject.

The letter to the Galatians deals with this problem of the Law. Paul's plan was to establish communities throughout the Eastern Empire, and then stay in touch through letters or revisit them to see how they were doing. Galatia was a province in central Turkey. Apparently, after Paul left, others came along and taught a different gospel. Paul was outraged by this. As he said, “Even if delivered by angels, there IS no other gospel than his.” This different gospel advocated circumcision, dietary laws, and Sabbath duties, the very thing that Paul had fought against. So, he repeated his teaching on this matter for those communities.

Turning to scripture, he found his rationale in the story of the call of Abraham in Genesis 12. With both the name (father of nations) and the promise, Paul claimed that gentiles were included in this original covenant (“nations,” in Greek, ethnos, is what is translated as "gentiles"). But then, why did God give the Law of Moses, which limits inclusion? Paul argued that the Law served as a pedagogus. A pedagogus was a tutor, most often a slave, who accompanied young boys to school, and also offered classes in the home. In other words, the Law served as a guide to define sin, for if we did not know what sin was, how could we choose? But now Christ is the “telos of the Law.” Some Bibles translate this as “the end of the Law,” but more accurately, it means “the goal of the Law.”

Does this mean that Jewish followers of Christ no longer had to follow the Law? Of course not - if you are born under the Law, you are required to follow it.

Over the centuries, Paul's teaching was summed up in the phrase, “the law-free mission to the gentiles,” but this is really a misnomer and led to many wrong conclusions on Paul's thought. His gentiles were to be free of circumcision, dietary laws, and Sabbath regulations, but they were not totally free from the Law. Do not imagine for one moment that Paul let his gentiles continue with idolatry or any other pagan customs, and he incorporated Jewish ethical and charitable concepts into his communities. In his book, Paul, E. P. Sanders applies modern social scientific methods to the study of Paul's views of the Law and concludes that he follows a pattern of religion, or how one gets in, and how one stays in. For Paul, the gentiles get in not by following the Law, but once in, they follow the Law (or Paul's version of it).

Another phrase of Paul's became the basis of centuries of commentary, culminating in Martin Luther's separation from the church of Rome. Paul claimed that gentiles are saved by faith alone, and not by works of the Law. What he meant by works of the Law were those ritual barriers between communities: circumcision, dietary laws, etc. But for centuries, it was understood as the great divide between Judaism and Christianity. A careful reading of his letters indicates that Paul is not setting himself up against Judaism per se, but against those other Christians who believe that gentiles have to become Jews first before entering the community. Who were these other Christians? We think they were probably gentile-Christians, not Jews. So why would gentile-Christians advocate circumcision?

Paul says that after he had been in the mission field several years, he went up to Jerusalem for a meeting over the gentiles (which may or may not be the meeting Luke relates in Acts 15). The timing was odd (scholars place the meeting circa 49/50). And, according to Luke, gentiles had been approved after Peter's meeting with Cornelius, so why, years later, is a meeting required to settle the issue? One theory is that time was passing and Jesus had not returned. Perhaps some gentile-Christians thought they had erred by not becoming Jews first and thought that by doing so, it would help speed up the time for the end.

Paul is not worried about the time in the same way. With his own experience, he decided that when his gentiles turned to the God of Israel, this was a sign of the final days (an element of the prophetic tradition concerning the final intervention by God). As “Apostle to the Gentiles,” his role among this group was crucial to ushering in these final elements. In other words, the kingdom waits upon Paul's reaching as many gentiles as he can. Once that is accomplished, then the Jews will see the light and join (Romans 9-11).

Death

We cannot confirm where or how Paul died. Paul's letter to the Romans is most likely one of his last surviving works in which he told his audience that he was going to Jerusalem for a visit and then would come to Rome to see them (with plans to continue on to Spain). Luke told the story of Paul's arrest in Jerusalem, where he (as a Roman citizen) had the right to appeal to the Roman emperor. The Book of Acts ends with Paul under house arrest in Rome, continuing his preaching. It is only in later, 2nd-century CE, narratives that we find legendary material of Paul's trial in Rome (with alleged letters between Paul and the Stoic philosopher, Seneca). After conviction, he was beheaded and his body buried outside the walls of the city, on the road to Ostia, so that his grave would not become a shrine. Years later, this site would become the current basilica in Rome, St. Paul's, Outside-the-Walls, and the Vatican has always claimed that his body rests in a sarcophagus within the church.