Cilicia Campestris was one of the six districts of the Roman province of Cilicia organized by Pompey the Great (l. c. 106-48 BCE) in 64 BCE. The name translates roughly into “Cilicia of the Plains” and corresponds to the earlier name for the area, Cilicia Pedias which meant “smooth” or “flat” Cilicia as contrasted with the more mountainous and difficult terrain of Cilicia Trachea (renamed Cilicia Aspera by Pompey). The six districts of Cilicia as organized by Pompey were:

- Cilicia Campestris

- Cilicia Aspera

- Pamphylia

- Pisidia

- Isauria

- Lycaonia

Cilicia Campestris was the most valuable of these because of its fertile plains which produced abundant crops. Its capital was Tarsus, an ancient city which, by the time of the Roman Empire, was a wealthy metropolis. C. 297 CE, in the reign of Diocletian (r. 284-305 CE), Cilicia was redistricted. Cilicia Campestris then became Cilicia Prima, Cilicia Aspera was Cilicia Secunda, and a third district was created named Isauria.

Cilicia, as defined by Diocletian, remained under Roman control until the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE, at which time it came under the provenance of the Eastern Roman Empire (also known as the Byzantine Empire) which held it until c. 700 CE when the region was taken in the Muslim Invasion. The territory then reverted back to Byzantine control in 965 CE until the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453 CE, after which it was claimed by the Ottoman Empire.

Cilicia Campestris is famous as the birthplace of Saint Paul of Tarsus and the site of his earliest evangelical missions. Delegates from the Christian communities of Cilicia participated in the Synod of Antioch in 268 CE and the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE, both of which encouraged Christian orthodoxy in the region. It is visited in the present day, in fact, for the architecture of its religious structures as often as for the impressive landscape and resonance of its past.

Early History

Archaeological evidence from Cilicia has established human habitation dating back to c. 9000 BCE along the southern coast although it is probable that human beings were living in that area earlier. It has been suggested by some scholars (notably the British archaeologist Andrew Colin Renfrew in his Anatolian Hypothesis) that Proto-Indo-European (the ancestor of Indo-European languages) originated in and spread from Anatolia, including the region later known as Cilicia, sometime between the 7th-6th millennia BCE.

This hypothesis is quite probable considering the influence of the Phoenicians on the region. Scholar William H. Stiebing Jr. notes:

The most important contribution of the Phoenicians to other cultures was the alphabet. The Phoenicians used the Canaanite alphabet, a direct descendent of the Proto-Canaanite alphabet developed in the early part of the second millennium BCE. The Phoenicians introduced the alphabet into Cilicia, from whence it may have spread into central Anatolia. (253)

The broad scope of the coast of Cilicia on the Mediterranean would have been the point of departure for cultural transmissions such as the alphabet by sea at the same time similar exchanges were taking place through trade by land.

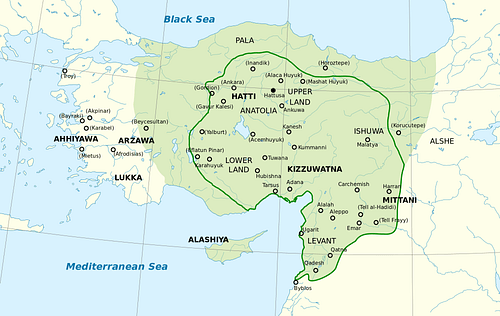

The Hatti and Luwian peoples inhabited the region from c. 2700 BCE before and after it was conquered by Sargon of Akkad (r. 2334-2279 BCE). After the fall of the Akkadian Empire in c. 2083 CE, the Hatti controlled the region from their stronghold at Hattusa before the coming of the Hittites who held the area from 1700 - c. 1200 BCE and knew the region as Kizzuwatna. The Assyrians, who later succeeded them, named it Hilikku from which comes the Greek Kilikia and so Cilicia. The Assyrians were followed by the Persians, Alexander the Great, the Seleucid and Ptolemaic empires, before the coming of Rome in 103 BCE.

The Cilician Pirates

Toward the end of the Hittite Empire, the Sea Peoples appeared; an alliance of different nationalities who ravaged the region c. 1276-1178 BCE and are primarily known from the inscriptions of the Egyptian pharaohs Ramesses II (r. 1279-1213 BCE), Merenptah (r. 1213-1203 BCE), and Ramesses III (r. 1186-1155 BCE) who finally defeated them in 1178 BCE, after which they not heard of again.

Stiebing (among others) claims Cilicians formed part of this pirate band noting that a people known as the Danuna are included in ancient inscriptions and were most likely from the Cilician city of Adana (224). If so, the Sea Peoples would be the first mention of the later and more famous coalition known as the Cilician pirates.

The Cilician pirates' activity is usually dated as beginning around the 2nd century BCE, but it is probable that the piracy of the Sea Peoples was continued by others in the region and that the Cilician pirates were operating much earlier. It should also be noted that 'Cilician Pirates' is a convenient term for a multinational coalition of thieves, kidnappers, and robbers who harassed the Mediterranean in much the same way the Sea Peoples had centuries earlier. Cilicia, especially the less hospitable area of Cilicia Aspera, was simply the most convenient headquarters for Mediterranean pirates; not all those pirates were Cilician.

The region had been under the control of the Seleucid and Ptolemaic empires but, beginning c. 110 BCE, their hold on Cilicia weakened and Tigranes the Great of Armenia (r. c. 95 - c. 56 BCE) took the eastern part of the region. Tigranes encouraged Armenian settlement of the lands and, at the same time, the Cilicians took advantage of the lack of governmental control to expand their operations. The Ptolemies and Seleucids had both been aware of the piracy problem but had tried to ignore whatever problems it caused as the economies of both depended on the slave trade which was the mainstay of the pirates.

Roman Republic & Cilicia

Rome first tried to address the problem of the Cilician pirates in 140 BCE, sending Scipio Aemilianus to assess the situation and make recommendations. Scipio reported that immediate action should be taken but Rome chose not to move on this, most likely because the Romans, like the Seleucids and Ptolemies, relied so heavily on the slave trade. In 103 BCE, Marcus Antonius (l. 143-87 BCE, grandfather of Mark Antony) took Cilicia Pedias in a campaign against the pirates. Although he established Roman presence in the region and disrupted the pirates' initiatives, he failed to crush them and, in fact, his own daughter Antonia would later be kidnapped by Cilician pirates and held for ransom.

The same thing would happen to a young Julius Caesar in 75 BCE who famously objected to the ransom the pirates demanded, claiming he was worth much more. Between 78-74 BCE, the consul Publius Servilius Vatia (served 79 BCE) launched a campaign against the Isaurians of Cilicia and, like Antonius, was victorious but still could not put an end to Cilician piracy. The job then fell to Pompey the Great who took on the pirate problem in 67 BCE as part of his campaign against Mithridates VI of Pontus (r. 120-63 BCE).

Mithridates VI had allied himself with Tigranes the Great of Armenia (r. c. 95 - c. 56 BCE) on land but entered into pacts with the Cilician pirates to harass the Romans by sea. The Cilician pirates disrupted trade, raided coastal cities, and kidnapped free Romans, Greeks, and any others they could force onto their ships to sell as slaves. Earlier attempts by the Romans to curb the pirates had struck at them on land; Pompey took the fight to the seas.

He divided the Mediterranean into thirteen districts which would each be patrolled by its own fleet and commander. As the pirates in each of these districts were defeated, the crews were interrogated for information on the hidden harbors and coves of others who were then captured and, if they did not submit, killed. By 66 BCE, Pompey had crushed the Cilician pirates although piracy in the Mediterranean would continue to pose problems through other agencies for centuries to come.

The pirates who had surrendered were relocated and settled in Cilicia Campestris which, as noted, was only the central district of the six Pompey created in Cilicia proper, which was recognized as a Roman province in 64 BCE, with the island of Cyprus added to the territory in 58 BCE. The civil war between Caesar and Pompey interrupted any further Roman action in the region, but after his victory, Caesar reorganized the province in 47 BCE, redistricting and linking Cilicia more closely with Syria. In 27 BCE, Augustus (r. 31 BCE - 14 CE) joined Cilicia to Syria as the province of Syria-Cilicia Phoenice, thus combining the regions. It is for this reason that Cilician cities, most notably Tarsus, are often cited by ancient historians as being Syrian.

Province of the Empire

Augustus consolidated his new empire and expanded the frontiers. His efforts in Syria-Cilicia Phoenice were only one aspect of a much larger enterprise as he initiated campaigns across the Rhine River and expanded Rome's territories in order to firmly establish frontiers and stabilize the interior of the empire. Provinces were defined as either senatorial or imperial: senatorial provinces, those within the borders, had governors appointed by the Roman Senate while, in imperial provinces on the empire's frontiers (such as Cilicia), only the emperor had the power to appoint a governor. Some of these governors served with distinction, but this was not always the case. A 1st-century CE governor, Cossutianus Capito, was accused by the Cilicians of extortion and corruption and, after being found guilty, was stripped of his senatorial honor, at least for a time.

The idea behind the imperial province was to limit appointments to men who could be trusted to remain loyal rather than give in the temptation to raise troops and challenge the emperor. This is precisely what did happen, in fact, during the Crisis of the Third Century (235-284 CE) when 'Barracks Emperors' seized power in Rome consistently. The frontiers were also the areas most open to religious innovation and belief and where most of the sects which flourished in the 1st century CE found their earliest adherents. The state religion of Rome was a part of one's home and public life – and this was no different in the provinces than the capital – but the further away a community was, the freer some people seemed to feel in exploring religious expression.

Religion in Cilicia

In Cilicia, one of these people was Saul of Tarsus, a Roman citizen by right of his birth in a Roman province but a devout Cilician Jew. There were a significant number of Jewish communities in Cilicia who were free to worship as they pleased as per an edict of Julius Caesar which was continued by Augustus. Judaism prohibited adherents from sacrificing to the Roman gods, maintaining there was only one true God, and further separated themselves from the Gentiles through traditions such as the kosher diet, circumcision, and reliance on scriptural revelation of God's will. Non-Jews (known as Gentiles) in Cilicia were drawn to the religion for a number of reasons including its moral code and belief in a single god.

According to the biblical book of Acts, Saul was sent to Jerusalem as a young man to study and became a Pharisee, an adherent and teacher of orthodox Judaism (Acts 22:3). He persecuted the members of a religious sect in Jerusalem called the Galileans and was on his way to Damascus to find more when he experienced a profound transformation. He heard a voice which identified itself as Jesus Christ asking why Saul was persecuting him and then fell to the ground blinded (Acts 9:3-9). Contrary to popular opinion, Saul did not then change his name to Paul. Paul was most likely his Roman name as suggested by Acts 13:9 which states “Saul was also called Paul” and intimates this was prior to his conversion.

Paul set about converting the ancient world to the religion of Jesus Christ as revealed to him after his conversion, and his missions began in Roman Cilicia. The Jewish sympathizers (also known as Sabbatists because they would observe the Jewish sabbath) would have been among Paul's earliest converts as the religion he was preaching was basically Judaism-Without-the-Law. These Gentiles could embrace the morality, ritual, and the day of rest they had found so attractive in Judaism without full conversion, and as Paul's religion gained wider acceptance, the fear of losing contact with family and friends greatly diminished.

Christianity flourished in Cilicia Campestris as well as greater Cilicia and, after Rome legitimized the religion in the 4th century CE, Cilician bishops participated in the Synod of Antioch in 268 CE (which argued for the divinity of Jesus, among other theological points) as well as the famous Council of Nicaea in 325 CE, which formalized orthodox Christianity. Judaism remained popular in Cilicia, and Mithraism continued to be practiced, as well as Zoroastrianism and other mystery religions including the ancient faith of the Hatti who worshipped a Mother Goddess who was known by this time as Cybele but could have been the same deity earlier known as Atheh.

Byzantine Cilicia

In 72 CE, Vespasian had united Cilicia Campestris and the other of Pompey's districts with the rough and relatively isolated Cilicia Aspera. The region remained unified throughout the duration of the Western Roman Empire, and various emperors made their marks on the region. The emperor Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE) named the province Hadriana, and Decius (r. 249-251 CE) had it renamed Decia. Constantius II (r. 337-361 CE) built the Misis bridge across the Pyramus River (modern-day Ceyhan River) in the city of Mopsuestia. The bridge was renovated and restored by Justinian I (r. 527-565 CE) and is still in use in the present day.

During the period of the Republic and Empire, Cilicia engaged in the same kind of trade it always had, exporting olives, wine, cereals, grains, beans, fish, tents, and cilicium which was a rough cloth of goat hair used primarily in tent-making. Under the name 'cilice', this cloth would become popular among Christians who wore it as penance either openly or under their clothing and would continue as a major export up through the Middle Ages (c. 476-1500 CE).

When the Western Roman Empire fell in 476 CE, Cilicia became part of the Byzantine Empire of the east. The Byzantines defended the region from encroaching Muslim invaders throughout the 7th century CE, but it was finally conquered c. 700 CE. Cilicia became a no man's land frontier between Byzantine Christian and Arab Muslim forces, with the Muslims frequently using the region as a staging area to launch raids into Byzantine lands for loot and slaves.

The raids were orchestrated so quickly that the Byzantines could not defend against them until finally, in the 10th century CE, the Byzantines struck back under their warrior emperor Nikephoros II Phokas (r. 963-969 CE). Nikephoros invaded Cilicia, driving the Muslim forces before him, and re-established Byzantine control over the region in 965 CE, refortifying the mountain stronghold of Sis. Cilicia Prima and the rest of the region flourished afterwards for centuries, eventually attracting Armenian settlers who allied themselves with the Byzantines as the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia (1080-1375 CE), an important ally of the Europeans during the First Crusade (1096-1099 CE). After the Byzantine Empire fell in 1453 CE, the region was added to the Ottoman Empire which held it until after World War I when it became part of the Republic of Turkey.

The rich history of Cilicia continues to draw people's interest in the present day. Aside from its ancient resonance for people of different faiths worldwide, it has also become a pilgrimage site, along with other parts of Cilicia, for those who lost relatives in the Armenian Genocide (c. 1914 - c. 1923 CE) of the Ottoman Empire. The region is frequently visited by tourists for those impressive Armenian churches not converted to mosques, the striking mosques themselves, as well as the ancient ruins of Roman roads, buildings, gates, and temples from a time before either faith even existed.