The “Barracks Emperors” is a term coined by later historians referring to the Roman emperors who were chosen and supported by the army during the period known as the Crisis of the Third Century (also known as the Imperial Crisis, 235-284 CE). In 235 CE Emperor Alexander Severus (222-235 CE) was assassinated by his troops who then chose their commander Maximinus Thrax (235-238 CE) as ruler. Maximinus became the first of these so-called “barracks emperors” who would continue to rule Rome right through the reign of Carinus (283-285 CE) and who characterize the period of instability in Rome during this period. The Crisis of the Third Century was resolved by Emperor Diocletian (284-305 CE) who addressed the causes of the crisis and secured the future of Rome.

The barracks emperors rose in response to a series of threats to the stability of the state, both internal and external. The Severan Dynasty, of which Alexander was the last, had begun a practice of enlarging the army while also increasing a soldier's pay. In order to afford this large military, Septimus Severus (193-211 CE) debased the currency by adding less precious metal to coins in order to produce more of them. This policy would be adhered to by later emperors and resulted in widespread inflation and a lack of confidence in purchasing power on the part of the citizens.

In addition to the currency problems, a plague swept the land, depopulating and destabilizing communities, the labor force. Further, incursions by barbarian tribes across Roman borders were also upsetting the social and economic balance of the state. At the same time, the Severan Dynasty's elevation of the military (more necessary than ever to combat invasions and other external threats) placed the emperor in an almost subordinate position to his army's commanders. Emperors now felt they had to placate and court the favor of the soldiers rather than objectively govern for the good of all the citizens of Rome.

The emperor had always relied on the support of the military to some degree but now such support became more imperative. Whereas in the past an emperor came to power through a system of succession – either as the son or adopted heir of the sitting emperor – he was now chosen by the military based on his popularity with the troops, generosity toward the military, and his ability to attain immediate and discernible results. When any of these criteria were disappointed – especially the last – he was assassinated and replaced by another. This paradigm characterized all of the barracks emperors and is the major difference between them and those who ruled before and after the Crisis of the Third Century.

The Emperors & Their Reigns

The barracks emperors were all unique individuals with their own strengths and weaknesses, triumphs and failures but, generally speaking, were defined by a desire for the personal benefits of power without possessing the character to wield that power effectively. Because of the uncertainty of the times and the real or perceived threat of imminent invasion on the part of the populace, the Senate, and the military, a man who showed himself a strong, courageous, and – most importantly – effective military leader would be chosen as emperor by his troops. This decision was then either supported by the Roman Senate based on the person's reputation or forced on the Senate and the people by the military.

The barracks emperors and their respective achievements, as well as their timely or untimely ends, were:

Maximinus Thrax (235-238 CE), a Thracian commander who, owing to his nationality, feared he would not be respected by the Senate or citizenry and so chose to carve out his own fame through campaigns in Germany. Although successful, these campaigns were so costly that they drained the treasury. Maximinus operated on his own whims, disregarding the pressure put on his troops or the general good of the empire. His reign resulted in civil war, as the Senate elevated others who were sent to remove him. He was killed by his own commanders in an effort to end the hostilities.

Gordian I and Gordian II (238 CE, March-April) were father and son who took part in the attempt to overthrow Maximinus. Gordian II was killed in battle fighting pro-Maximinus forces and Gordian I committed suicide upon hearing of his son's death.

Balbinus and Pupienus (238 CE, April-July) were two emperors the Senate raised to oppose Maximinus. They were unpopular with the people, who actually pelted them with stones as they walked in the street, and were eventually assassinated by the Praetorian Guard.

Gordian III (238-244 CE) co-ruled with Balbinus and Pupienus until they were assassinated and was then proclaimed emperor by the military supporters of Gordian I and Gordian II. He was only 13 years old when he came to power and was controlled by his mother and later by his father-in-law. His reign was considered ineffective, and he was assassinated, probably by his successor Philip the Arab.

Philip the Arab (244-249 CE) also known as Julius Philippus was the Praetorian Prefect under Gordian III and took power after assassinating him. To assure a smooth succession, he made his son, Philip II, his co-emperor and embarked on a number of successful campaigns. He concluded a peace with Persia and won a number of victories over the Goths after which he celebrated Rome's 1000th anniversary as a city. The provincial army commanders disliked him, however, and he was killed in battle by one of them: his successor Decius. Phillip II was assassinated soon after his father's death.

Decius (249-251 CE) was a senator and consul before being appointed to a command in the Danube region where he rose to power with the support of his troops. He inaugurated the systematic persecution of the Christian sect by requiring citizens to make sacrifices to the state gods in the presence of officials. This policy and the resultant martyrdom of many Christians did nothing but popularize the new faith. He followed Philip's policy and made his son his co-emperor, but both were killed in battle fighting the Goths under King Cniva at the Battle of Abritus in 251 CE.

Hostilian (251 CE, June-November), the younger son of Decius, was made co-emperor by Gallus when Decius was killed in battle. He died soon after from the plague.

Gallus (251-253 CE) was a commander under Decius who became emperor upon his death. He also made his son, Volusianus, co-emperor; both were assassinated by their own troops who elevated Aemilianus.

Aemilianus (253 CE, August-October), was a regional governor chosen by the troops who proved disappointing and so was quickly assassinated in favor of Valerian.

Valerian (253-260 CE) made his son Gallienus co-emperor as he realized the empire was too large for one man to govern. Gallienus was responsible for the western part and Valerian for the eastern section of the realm. On campaign in the east, he was captured by the Sassanid Persians and died as their prisoner. He was the first Roman emperor ever to be captured by the enemy and, as he followed Decius' policy of severely persecuting Christians, this was seized upon by the Christian sect as an act of their god and vindication of their sect.

Gallienus (253-268 CE) was an effective ruler and military leader who managed to control the chaos of the Roman Empire to the extent that cultural, literary, and philosophical advances developed under his reign. He also initiated a number of important changes in the military, most notably expanding the role of the cavalry. Even so, he could not escape the climate of the times and was assassinated by his own troops on campaign in a conspiracy involving the future emperor Aurelian.

Claudius Gothicus (268-270 CE) was an officer of the cavalry under Gallienus who proved himself an able leader and administrator. He defeated the Alamanni, put down a rebellion by the would-be usurper Aureolus, and received his honorary epithet “Gothicus” following his victories over the Goths. Claudius might have gone on to greater accomplishments but was stricken by the plague and died.

Quintillus (270 CE), the brother of Claudius Gothicus, came to power briefly following the latter's death but died soon after, probably assassinated by Aurelian.

Aurelian (270-275 CE) was a co-commander of Gallienus' cavalry with Claudius and, when Claudius came to power, served under him. Aurelian, like Gallienus and Claudius, is one of the few Barracks Emperors who placed the good of Rome above his own personal ambition. He restored the empire by securing its borders and bringing the breakaway territories of the Gallic and Palmyrene empires back under Roman control. Still, none of these accomplishments was enough to protect him, and he was assassinated by his commanders who feared he planned to have them executed.

Tacitus (275-276 CE) was an elderly senator selected by the Senate as emperor following Aurelian's assassination. He ruled for only nine months, during which he was engaged in constant warfare before he died either of natural causes or – more likely – was assassinated.

Florianus (276) was the brother of Tacitus and reigned for only three months before he was assassinated by his own troops in favor of Probus.

Probus (276-282 CE) was enthusiastically supported by his troops in the Balkan region and became emperor on the death of Florianus. His reign was marked by almost continual military campaigns but, as he had a background in farming, he emphasized the importance of agriculture between engagements. This interest, according to one report, may have led to his downfall. One of his officers, Carus, became increasingly popular with the men who made him emperor while Probus was assassinated by troops who had grown tired of forced agricultural labor.

Carus (282-283 CE) was the prefect of the Praetorian Guard under Probus and avenged his former emperor's murder after he came to power. He made his sons Numerian and Carinus co-emperors and placed them in control of the west while he campaigned toward the east against the Sassanid Persians. He was reportedly killed on campaign when struck by lightning.

Numerian and Carinus (283-285 CE), Carus' sons, were co-emperors after their father's death. They both led military campaigns in attempts to secure the borders, and Carinus also successfully put down a revolt from within the empire. Numerian developed an eye disease, and either died of natural causes or was assassinated, while Carinus was killed by his own troops in battle with his successor Diocletian.

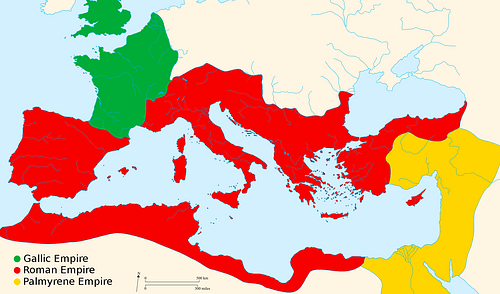

Along with these barracks emperors, there were two other rulers whose actions would have a significant impact on Rome's course during the crisis: Postumus (260-269 CE) in the west, who founded the Gallic Empire, and Zenobia (267-272 CE) in the east, queen of the Palmyrene Empire.

Breakaway Empires

Under the reign of Gallienus, Postumus was governor of Upper and Lower Germany. When Valerian was captured by the Sassanid Persians, Gallienus was left alone to defend the empire and this encouraged Postumus to assert his authority. Gallienus' son and heir, Saloninus, had been sent to Postumus' region for safety along with Silvanus, the prefect of the Praetorian Guard, to defend him. Postumus had already defeated marauding German tribes making incursions into his territories but was limited in his powers by his position; he was only a regional governor, not the emperor, and lacked the authority he felt he needed to defend his territory. Gallienus was thoroughly engaged in his own battles, and Saloninus at Cologne was unable or unwilling to commit to the level of leadership in the region Postumus felt necessary.

In 260 CE, Postumus marched on Cologne, took the city, and executed Saloninus and Silvanus; he then proclaimed himself emperor of the region. He sent messages to Gallienus explaining why he had acted as he did, professing his loyalty to Rome, and promising that he would not raise arms against the empire or encroach on any Roman territories. In spite of this, Gallienus could not afford to allow such a large segment of his empire – Gaul, Germania, Hispania, and Britannia – to simply leave. In 263 CE Gallienus drove his troops into Gaul in an attempt to dislodge Postumus but was wounded by an arrow in battle and withdrew.

Postumus continued his reign, and kept his promise to protect and defend Rome, until he was killed by his own troops in 269 CE when he refused to allow them to sack one of his own cities (modern-day Mainz) which had rebelled. A blacksmith (and possibly foot-solider in the army) named Marius (269 CE) was then proclaimed emperor by the troops but was assassinated shortly afterwards, and the Praetorian tribune Victorinus (269-271 CE) became emperor. Although Victorinus was an able military commander, his inability to keep his hands off other men's wives led to his murder by one of his commanders, and the usurper Domitianus (271 CE) took control. He was defeated in battle by Tetricus I (271-274 CE), an able administrator and military leader and considered the only true successor to Postumus.

Tetricus I made his son (also named Tetricus) co-emperor to share the responsibilities of government and run the empire more efficiently. He stabilized the region, putting down rebellions by the German tribes, but his reign was interrupted – and then ended – by Aurelian in 274 CE at the Battle of Chalons. Aurelian marched on the Gallic Empire after defeating and reabsorbing the Palmyrene Empire which had formed under the queen Zenobia, wife of the late Roman governor of the region, Odaenthus.

When Valerian was captured in 260 CE, and Gallienus could do nothing about it, the Roman governor of Syria, Odaenthus, raised an army and attacked the Persians. Although he failed to free Valerian, he did push the Persian forces back from the borders of the eastern side of the Roman empire. He further served Gallienus by helping put down a rebellion inside the empire by a would-be usurper, and for these efforts, Gallienus made him governor of the entire eastern part of the empire which ran from Syria down through the Levant.

Odaenthus was killed on a hunting trip in 266/267 CE, and his wife Zenobia became regent for their young son Vaballathus. Zenobia, like Postumus, was careful not to alienate her realm from Rome or antagonize the emperor but entered into negotiations with neighboring states, annexed Egypt, issued her own currency, and had herself and her son addressed by titles reserved only for the ruling family of Rome.

She had her own court, her own seal, her own commander-in-chief, and her own army, and was empress of her own empire in everything but official title. She seems to have hoped, like Postumus, that by remaining on good terms with Rome and performing military services which only benefited the empire, that she would be left alone to rule her region and her son might one day be chosen emperor.

Zenobia was, in fact, left alone while the emperors of Rome were engaged in their perpetual warfare with outside threats and each other, but when Aurelian came to power, he turned his attention east as quickly as possible. At the Battle of Immae in 272 CE, he defeated Zenobia's forces and drove her back to Emessa where, in a second engagement, he was again victorious. With Zenobia defeated and her Palmyrene Empire again joined to Rome, Aurelian marched west and defeated Tetricus I in 274 CE, ending the Gallic Empire.

Aurelian showed mercy to both Zenobia and Tetricus I, as well as most of the cities and towns he marched on, and after restoring the empire set himself to the task of remedying the underlying causes of the Crisis of the Third Century. It is likely that he thought his show of mercy to his enemies would dissuade future rebellions but never found out as he was assassinated in 275 CE by his commanders.

Diocletian's Reforms

The Crisis of the Third Century and the reign of barracks emperors would continue after Aurelian until Diocletian came to power in 284 CE. Diocletian developed the policies of the best of the barracks emperors, Gallienus and Aurelian, in reforming the military, tightening the borders of the empire, and also introducing reforms in currency and the government. His tetrarchy (rule of four) divided the operation of the government between two men who had successors already in place when they took their positions; this ensured ease of succession and prevented the rise of would-be usurpers.

The time of the crisis and the barracks emperors passed into history as Diocletian went further in dividing the empire in two – the Eastern Roman Empire and the Western Roman Empire – as he realized the realm had grown too vast to be governed by one man or even by four. The mistake made by most of the barracks emperors was the belief that one could wield political power primarily for one's individual benefit rather than the good of one's state and fellow citizens. Consequently, they could easily be replaced when their methods or personal choices no longer suited the military or citizens. Neither of these groups had anything to lose in replacing one selfish ruler with another more to their liking. This model became so accepted that not even the best of the emperors could feel secure in their positions. Only after Diocletian's reforms would the model change and ensure the future of Rome for the next generations.