The Battle of Immae (272 CE) was fought between the forces of the Roman emperor Aurelian (270-275 CE) and those of the Palmyrene Empire of Zenobia (267-273 CE) resulting in a Roman victory and, ultimately, the capture of Zenobia and an end to her breakaway empire. Aurelian's use of strategy, turning the strength of Zenobia's forces to weaknesses, and his expert use of the element of surprise characterize the battle and led to his victory.

This engagement was not the decisive battle which toppled the Palmyrene Empire - that would come later at Emessa - but the Battle of Immae was almost a dress rehearsal for Emessa in that Aurelian would use the same tactics and Zenobia's forces would again be fooled by them and suffer another crushing - and final - defeat.

Zenobia had assumed rule of the eastern provinces of Rome after the death of her husband, Odaenthus, as regent for their son Vaballathus. She quickly took on the full responsibilities of leadership, however, without consulting Rome in any of her decisions. By 272 CE she had extended her territory from Syria and the Levant into Egypt and was in negotiations with the Persians when Aurelian defeated her forces and brought the Palmyrene Empire back under Roman control.

The Crisis of the Third Century

The rise of the Palmyrene Empire was possible because of the period of instability and civil war in Rome known as the Crisis of the Third Century (also as the Imperial Crisis, 235-284 CE). The period began with the assassination of the sitting emperor Alexander Severus in 235 CE by his troops who objected to his decision to pay off the Germanic tribes for peace instead of engaging them in battle. Following Alexander's death, over 20 emperors would claim rule of the empire in the next 49 years.

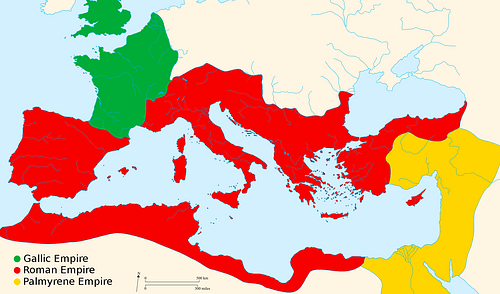

Civil wars, plague, a devaluation of the currency, widespread inflation, and threats from barbarian tribes at the borders all contributed to the instability of the empire at this time and allowed for the so-called "breakaway empires". In the west, the regional governor Postumus separated his territories from Rome as the Gallic Empire which included Germania, Gaul, Hispania, and Britannia, and in the east Zenobia quietly removed her lands from Roman control as well.

Although Zenobia's actions are often characterized as a rebellion, she was careful not to challenge Roman authority outright and, in fact, claimed to be acting in the interests of Rome. Postumus, after his initial strike against the emperor's heir and co-ruler, would claim the same: he was only doing what he thought best to defend the western territories against invasion during a time of crisis.

In spite of their protestations and official declarations, it is clear that both rulers had seized power of their respective regions and were acting autonomously without the consent or direction of the government of Rome. Even so, with so many threats – internal and external – to be dealt with, the emperors of Rome had little time or resources to bring either of these empires back under Roman rule. The emperor Gallienus (253-268 CE) attempted a campaign against Postumus but was driven back; no one, however, tried the same with Zenobia.

The Rise of Palmyra

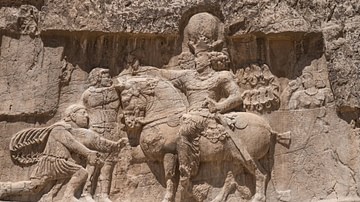

The Roman Emperor Valerian (253-260 CE) had made his son, Gallienus, co-emperor in 253 CE upon recognizing that the empire was too vast for one man to effectively govern. He placed Gallienus in charge of the west while he marched to secure the eastern regions against the Sassanid Persians. He was captured on campaign by the Persian king Shapur I (240-270 CE), and Gallienus, unable to come to his assistance, was left as the sole emperor.

Odaenthus proved himself an able commander, and his loyalty and value to Rome were further proven when he put down a rebellion against Gallienus. In recognition of his efforts, Gallienus made Odaenthus governor of the eastern provinces below Syria, stretching down through the Levant. In 266/267 CE, however, Odaenthus was killed on a hunting trip and Zenobia took the reins of government as regent for their son Vaballathus and maintained her late husband's policies and cordial relationship with Rome.

In the chaos of succession which characterized the Crisis of the Third Century, Odaenthus may have thought that he could be chosen as the next emperor by proving himself of value to Gallienus and by amassing his own wealth to mount campaigns by plundering the cities of the Sassanid Persians. After his death, Zenobia may have considered that her son, or even she herself, could rule Rome and so continued her husband's reign as he had conducted it in her official interactions with the Roman government; in her own region, however, she ruled as empress in everything but name. The historian Richard Stoneman writes:

During the five years after the death of Odaenthus in 267 CE, Zenobia had established herself in the minds of her people as mistress of the East. Housed in a palace that was just one of the many splendors of one of the most magnificent cities of the East, surrounded by a court of philosophers and writers, waited on by aged eunuchs, and clad in the finest silk brocades that Antioch or Damascus could supply, she inherited also both the reputation of Odaenthus' military successes and the reality of the highly effective Bedouin soldiers. With both might and influence on her side, she embarked on one of the most remarkable challenges to the sovereignty of Rome that had been seen even in that turbulent century. Rome, afflicted now by invasion from the barbarian north, had no strong man in the East to protect it...Syria was temporarily out of mind. (155)

Gallienus was assassinated in 268 CE and replaced by Claudius II who then died from fever and was succeeded by Quintillus in 270 CE. Throughout this time, Zenobia's policies steadily changed and, in 269 CE, seeing that Rome was too busy with its own problems to notice her, she sent her general Zabdas at the head of her army into Roman Egypt and claimed it as her own. Even this action could be justified as taken for the good of Rome since a rebel named Timagenes had instigated a revolt against the empire and Zenobia claimed she was only suppressing the rebellion. It is likely, however, that Timagenes was Zenobia's agent, sent to foment revolt to provide exactly the justification for invasion she needed.

The Battle of Immae

Aurelian had served with distinction under Gallienus as commander of the cavalry and then under his successor Claudius Gothicus (268-270 CE). He had a reputation as an effective leader who could see what needed to be done in any situation and acted swiftly to achieve results. In the period of the Crisis of the Third Century, these qualities in an emperor were highly prized, and Aurelian did not disappoint once he assumed leadership.

He secured the northern borders of the empire against an array of invading armies including the Jugunthi, Goths, Vandals, and Alammani, and later dealt severely with abuses concerning the official mint at Rome. He was able to control the chaos of the empire to the extent that regular practices of trade and commerce could be conducted as before. As soon as the most immediate threats were dealt with, he turned his attention east to Zenobia.

Unlike many of the other so-called "barracks emperors" of the period (those who came from the army), Aurelian was just as concerned for the well-being of the empire as he was for his own personal ambition and glory. He was not interested in entering into negotiations with Zenobia or sending messengers asking for explanations or justifications; as soon as he was reasonably ready to do so, he simply ordered his army about and marched on Palmyra.

Mercy proved to be very sound policy because the other cities recognized that they would do better to surrender to an emperor who showed compassion than incur his wrath by resisting. After Tyana, none of the cities opposed him and they sent word of their allegiance to the emperor before he ever reached their gates.

Whether Zenobia tried to make contact with Aurelian before his arrival in Syria is not known. There are reports of letters between them before the battle but they are thought to be later inventions. The Historia Augusta, a famous 4th-century CE work whose reliability is frequently questioned, includes a section on Aurelian and details his attempts to resolve the conflict with Zenobia peacefully. This section, by Vopiscus, includes a letter he allegedly wrote to her at the start of his campaign demanding her surrender and also her arrogant response; both are thought to be fabrications created to highlight Aurelian's merciful and reasonable approach to the conflict as contrasted with Zenobia's haughty retort.

While Aurelian had been on the march, Zenobia's general Zabdas had rallied her troops near the city of Daphne, near Antioch (in modern-day Turkey). Zabdas had complete confidence in his cataphracts (heavily armored cavalry) and the infantry who would support them. He arranged his army across the terrain to give his cavalry the greatest advantage in a charge. Aurelian, upon arriving, appeared to position his forces in a defensive response to Zabdas' formation.

Zabdas sent his cavalry against the Romans, forcing Aurelian to launch his own countercharge, and the two armies flew at each other. Just prior to engaging, however, the Romans wheeled their horses about, broke ranks, and retreated for their own lines. The Palmyrene cavalry followed quickly, and it would have seemed their victory was imminent, when the Romans turned back about and drove into them.

Zenobia's Defeat

Aurelian had used Zabdas' great advantages of the terrain and his cataphracts against him: the ground which was so perfectly suited for a cavalry charge worked both ways and the pursuit of Aurelian's lightly armored cavalry by Zabdas' with their heavier armor tired the Palmyrenes significantly before they engaged in the battle. The element of surprise, of course, must also be considered a factor in Aurelian's victory.

The Roman infantry had by now engaged the enemy but there was no longer any real fight left in them; very few of the cavalry had returned alive to Zenobia's lines. She and Zabdas fled the field with what men they had and regrouped at Emessa. Here Aurelian defeated them a second time using exactly the same tactics he had at the Battle of Immae but adding infantry armed with heavy clubs. The Palmyrene forces were unable to defend against these weapons and most were slaughtered. Zabdas is presumed to have been killed in this engagement as he is not mentioned again in any of the records. Zenobia, however, escaped and fled to Palmyra. Aurelian, after looting the treasury at Emessa, followed her, but she slipped out of the city with her son and again eluded him.

Precisely what happens next depends on which ancient source one reads, but in all of them, Zenobia is finally captured, brought before Aurelian, and taken back to Rome. The famous story of her being paraded through the streets in golden chains as part of Aurelian's triumph is almost certainly a later fabrication. Aurelian would have wanted to give the queen as little public attention as possible since it was already an embarrassment to him that he had needed to expend so much effort on subduing a woman. Whatever the details of her capture and transport to Rome, most sources agree that she married a wealthy Roman and lived out the rest of her days comfortably in a villa near the Tiber River.

Conclusion

The Palmyrene Empire was no more, and when Palmyra rose in revolt after their defeat, Aurelian returned and destroyed the city to make sure his position on rebellion was clear. He then marched to the other side of his empire and defeated Tetricus I of the Gallic Empire, slaughtering his army. Aurelian had restored the boundaries of the empire but would not live long enough to implement his policies regarding internal difficulties. He was assassinated by his commanders who mistakenly believed he was going to have them executed.

Had he lived, the Battle of Immae would have gone far in establishing Aurelian as a strong, decisive, but merciful emperor. When he first took Palmyra, he adhered to his policy of leniency and refused to have the members of Zenobia's court executed en masse; only select ringleaders were killed and those, it is thought, may have been implicated by Zenobia in order to save herself. It was only after the city rose a second time against him that he was forced to destroy them and their city.