Shapur I (r. 240-270 CE) is considered one of the greatest kings of the Sassanian Empire for expanding his realm, his policy of religious tolerance, building projects, and committing the Zoroastrian scriptures (Avesta) to writing. He was the son of Ardashir I (r. 224 - c. 240 CE), the founder of the empire.

Ardashir made him his co-ruler and brought him on campaigns to learn the art of war. Ardashir was a skilled military leader who not only defeated the Parthian king Artabanus IV (r. 213-224 CE) in numerous battles but finally killed him and brought down the Parthian Empire, replacing it with his own. Shapur I learned the lessons his father taught well and used them effectively against his own enemies, most notably Rome.

In the course of his wars with Rome, Shapur I proved himself a clever and unpredictable adversary. He held the distinction of being the first foreign ruler to capture a Roman emperor in battle (the emperor Valerian, r. 253-260 CE) and was doing well in his war of conquest against Rome until he made an enemy of the Roman governor of Syria, Odaenathus (died c. 267 CE), who defeated him in battle and drove him from Roman territory. After Odaenathus, Shapur I made no further moves against Rome, nor did his son and successor Hormizd I (r. 270 - c. 273 CE) who maintained an uneasy truce with Rome throughout his reign.

Although Shapur I wished to be remembered as a great warrior-king, he had other equally impressive talents. He was a brilliant administrator, instituted policies of religious tolerance, and encouraged the arts and culture. The architectural motif of the domed minaret was developed during his reign and would come to define his building projects and those of the region and culture up to the present day.

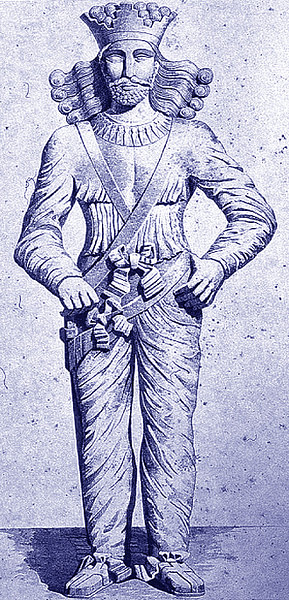

He is also often credited with the impressive archway known as Taq Kasra at the capital city of Ctesiphon (although this is also attributed to the later monarch Kosrau I, r. 531-579 CE). Shapur I was a popular monarch and was honored through inscriptions and, most famously, the Colossal Statue of Shapur I, located in the Shapur Cave in modern-day Iran.

Youth & Rise to Power

Shapur I had at least two brothers but seems to have been the favorite of his father from an early age. Ardashir I was the vassal of the Parthian king Artabanus IV (sometimes incorrectly cited as Artabanus V) who saw him and his family as trouble-makers. Ardashir's father, Papak, had taken control of the district of Istakhr where the ruins of the great Persian city of Persepolis lay. As the former capital of the Persian Empire, Persepolis held great significance for the Parthian Empire which claimed legitimacy for their reign through association with the former glory of the Persians. After Papak's death, Ardashir maintained control of Istakhr in defiance of Artabanus IV's authority as king and requests to relinquish the region.

When Artabanus IV had tolerated this long enough, he sent the vassal-king of Khuzestan against Ardashir but without success. Artabanus IV then met Ardashir in battle personally and was defeated both times; the second time he was killed. Ardashir then founded the Sasanian Dynasty (named for his forefather Sasan) on the ruins of the Parthian Empire. Shapur I was with his father on all of these campaigns.

While Ardashir was consolidating his power, the Parthian king of Armenia, Kosrau I, raised an army to oppose him and formed alliances with a number of powers, including the kingdom of Kushan and Rome. Ardashir did not wait for Kosrau I to launch an attack but mobilized his forces and struck first. The king of Kushan surrendered, and Kosrau I was defeated. Ardashir then sent Shapur I against Rome in Mesopotamia c. 230 CE.

Although the Roman writers claim that Shapur I was defeated in battle by the emperor Alexander Severus, all the Romans really did was halt Shapur I's advance. There is no evidence of a loss of Sasanian territory to the Romans nor any decisive Roman victories of note. Ardashir and Shapur I pressed on and, in the coming years, took a number of important Roman towns and cities. Ardashir was growing tired of rule and warfare and so made Shapur I his co-regent at this time, c. 240 CE; when he died later that year or in early 241 CE, Shapur I assumed the traditional Persian title of the monarchy, the King of Kings.

Administration & Religious Tolerance

Shapur I and his father were great builders whose palaces and temples showed a number of innovations, such as domed entrances and minarets, which became a staple of later Iranian architecture. Along with his principal wife, Azadokht Shahbanu (Shahbanu a title meaning"King's Lady"), Shapur I founded the center of learning and first teaching hospital Gundeshapur which would become the greatest intellectual center of its time and the model for later hospitals and universities. Gundeshapur was the first teaching hospital in which young aspiring physicians learned from older, more experienced, doctors. Ardashir I and Shapur I also understood the importance of religious faith in unifying an empire or nation and so made their own, Zoroastrianism, the state religion.

Even so, Shapur I also recognized that diversity encouraged vitality and so, from early in his reign, adhered to a policy of religious tolerance, allowing Christians, Jews, and other faiths to practice their religion freely. This atmosphere of tolerance allowed for the development of one of the most influential religious faiths of the ancient world – Manichaeism – whose founder, Mani (216-274 CE), had a place at Shapur I's court. Christians were allowed to build churches and Jews synagogues, even though their teachings were at odds with the state religion and, at times, antagonistic to it.

Zoroastrianism, with its vision of the universe in constant struggle between the forces of good and those of evil, light vs. dark, was perfectly suited to a state whose focus was primarily warfare. Shapur I saw himself as a leader of the forces of light and comported himself accordingly by encouraging the peaceful practice of all religions in his realm and devoting his scribes to the translation and revision of religious and philosophical works. At the same time, along with commissioning the construction of grand building projects, he led his armies against those he saw as the forces of darkness.

War with Rome

Although Shapur I was an able administrator and ruler whose reign is recorded in glowing phrases by everyone except Roman writers, he thought of himself as a warrior-king first and tried to exemplify this ideal. He took Roman fortresses and cities in Mesopotamia and drove his army on to conquer more territory, greatly enlarging the kingdom he had inherited from his father.

He was as skilled in battle as he was in bureaucratic administration and won a number of victories against Rome after Alexander Severus was murdered by his own troops on campaign in Germania in 235 CE. Severus' assassination plunged Rome into the chaotic period known as the Crisis of the Third Century (235-284 CE) during which over 20 emperors would rise and fall in almost 50 years. Shapur I took full advantage of Rome's confusion to further enlarge his kingdom.

Returning to campaign against the Romans in Mesopotamia, he was checked by the emperor Gordian III (r. 238-244 CE), only 17 years old at the time. Gordian III was an inexperienced soldier and statesman who relied heavily on the advice and strategies of his father-in-law and Praetorian Prefect, Gaius Timesitheus, a skilled leader and able commander. Shapur I was defeated by Gordian III's forces initially, but when Timesitheus died of the plague the situation reversed; Gordian III had no natural talents for warfare and no ability to counter Shapur I's strategies. After a number of setbacks for the Roman forces, Gordian III was killed by his own troops, who then replaced him as emperor with a popular commander, Philip the Arab (r. 244-249 CE).

Philip understood he needed to extricate himself from the war with Shapur I to deal with the many other challenges facing Rome. He made peace with Shapur I and paid him 500,000 denars as part of the treaty. According to Shapur I's inscriptions, Philip also agreed to Rome becoming a tributary, but this claim has been challenged. Philip ceded the disputed territory of Armenia to Shapur I but quickly went back on the treaty and reclaimed the region; this action obviously broke the peace and reignited hostilities.

Shapur I again struck at the Romans in Mesopotamia and conquered the Roman province of Syria, taking the city of Antioch. Antioch was one of the most important urban centers of ancient Rome, and its conquest could not go unchallenged. Emperor Valerian marched against Shapur I and drove him from the city, but the plague then struck the Roman army and they were forced to retreat back behind the walls of Antioch.

Shapur I lay siege to the city, and Valerian was forced to seek terms of surrender. He and his senior staff went out to meet Shapur I, expecting to be treated according to the rules of engagement they were used to but were instead taken captive. Shapur I did not consider the “forces of darkness” worthy of negotiation. The Sasanid army then intensified the siege of the city, under the direction of Shapur I's son Hormizd I, and Antioch fell. According to legend, Shapur I used Valerian as a footstool he had brought out each time he wanted to mount his horse, and when the emperor died, he had his body stuffed with straw and put on display in the palace for visiting dignitaries.

Shapur I & Odaenathus

Rome was in an almost constant state of chaos at this time as one emperor after another proved disappointing to his troops, the Senate, the people, or all three, and was executed in favor of another military commander. During the Crisis of the Third Century, elevating a man to the supreme position of emperor of Rome was almost a death sentence, but this did not prevent ambitious men from continually vying for the throne.

On the eastern border of the Roman Empire, the city of Palmyra in Syria was governed by a man named Odaenathus who seems to have considered Shapur I a better bet to advance his fortunes than any of the emperors of Rome. He sent Shapur I an offer of alliance, which was rebuffed. Shapur I replied that Odaenathus was not his equal and, far from thinking they could be allies, the Roman governor should look forward to becoming Shapur I's vassal.

Odaenathus was insulted and, claiming he was mobilizing his forces to free Valerian from the Sasanids, marched against Shapur I. He had at his command a troop of Bedouin soldiers, who knew the land as well as the Sasanid army, and his own Syrian troops were fully acclimated to the climate of the region, unlike those under Gordian III or Valerian who had been deployed from Rome. Odaenathus defeated Shapur I and drove him and his army from the Roman territories.

Shapur I's victory over Valerian was among his last. Regarding Odaenathus' campaigns, scholar Philip Matyszak notes how Shapur I “discovered that a well-led Roman army was still the world's finest fighting force” (239). Shapur I quickly lost any gains he had made and retreated back to his own borders. Odaenathus was rewarded for his services to Rome by elevation in rank to governor of the entire province of Syria. When he was killed on a hunting trip c. 267 CE, rule would pass to his young son but power would be wielded by his wife Zenobia (r. 267-272 CE) who would found the Palmyrene Empire.

Conclusion

Following his defeat by Odaenathus, Shapur I focused on domestic issues and warfare with nations on his other borders. He kept a wary peace with Rome but never moved against it again. He continued to encourage a high level of literacy and culture at his court, which was to serve as a model for the rest of the citizens. Matyszak notes how “Persian noblemen of Shapur's time were cultured individuals who were expected to have a knowledge of literature and the arts. Many played chess, polo, or an early form of tennis” (242). Shapur I maintained a stable and prosperous empire until his death when he was succeeded by Hormizd I who would continue his policies but was never as effective a monarch as his father had been.

The statue is an intricately carved piece, which was decorated in antiquity with jewels and was so carefully created that, even in its present ruinous state, the image of the great king remains impressive and gives some idea of the grandeur of his reign. Although he was defeated by the Roman forces under Odaenathus, he maintained his kingdom and continued his policies of justice, religious tolerance, great building projects, and cultural diffusion, handing this legacy on to his son who continued them. His reign is consistently praised by non-Roman scribes for all of these accomplishments, and he continues to be regarded as a King of Kings, with the same level of respect he knew while he lived, up to the present day.