Tigranes II or Tigranes the Great ruled as the king of Armenia from c. 95 to c. 56 BCE. Expanding in all directions, at its peak, Tigranes' Armenian Empire stretched from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. Not before or since would Armenians control such a huge swathe of Asia. Tigranes would only be checked once his kingdom became enmeshed in the ambitions of the two regional superpowers, Parthia and Rome, when his alliance with Mithridates VI, king of Pontus, proved his undoing.

The Artaxiad Dynasty

The Artaxiad (Artashesian) dynasty had replaced the Orontid dynasty and ruled ancient Armenia from c. 200 BCE to the first decade of the 1st century CE. Founded by Artaxias I (r. c. 200 - c. 160 BCE), the dynasty would ensure Armenia enjoyed a sustained period of prosperity and regional importance and no one would contribute more than their greatest king Tigranes II, widely considered the most important and successful ruler in Armenia's entire history.

Succession

After a rather dim period for the historical record of Armenia, a shining light suddenly arrives on the scene with a mass of documentation covering the reign of Tigranes II (aka Tigran II). There is the caveat that most sources, and all contemporary ones, are from the Romans and so they tend to be more than a little biased against one of their more serious foes in the east. Later sources help redress the balance but these can also have their problems in their sometimes obvious selection and omission of events for patriotic reasons.

Tigranes was put upon the throne of Armenia by the Parthians after his uncle, the Armenian king Artavasdes I, had been forced to send Tigranes as a hostage to the Parthians following his military defeat to that state. When his father Tigranes I died c. 95 BCE, Tigranes was sent back to Armenia to take his place on the throne. The new king had to cede the “Seventy Valleys” to the Parthians (a territory probably towards modern Azerbaijan) but he soon proved to be anything but a compliant client ruler.

Expanding the Empire

Tigranes was able to take advantage of the crumbling of the Seleucid Empire as well as the Parthians being distracted by the still chaotic aftermath of Mithridates II's death in 91 BCE and invasions on their eastern borders. The Armenian monarch could thus set about expanding his own kingdom even further. First, he annexed the other part of traditional Armenia, the kingdom of Sophene in 94 BCE. With formidable siege engines and units of heavily-armoured cavalry, he then re-took the “Seventy Valleys” and went on an extended spree of conquest from 88 to 85 BCE. He conquered Cappadocia, Adiabene, Gordyene, Media Atropatene, Phoenicia and parts of Cilicia and Syria, including Antioch. The latter city invited him to be their king and subsequently minted silver tetradrachm coins with images of Tigranes wearing his eastern tiara and, on the reverse, a woman with a turreted crown and holding the palm of victory. The Armenian king even sacked Ecbatana, the Parthian royal summer residence in 87 BCE while the Parthians were struggling to deal with invading northern nomads.

Another policy of Tigranes', besides conquest, was to improve trade relations with certain states, notably Babylonia. Trade contacts were set up with the Skenite Arabs, through whose territory goods could be exchanged with Babylon. This was also the reason why Tigranes took no risks and installed his brother as ruler of Nisibis which controlled trade from Mesopotamia to the west.

King of Kings

From 85 BCE, having acquired a decent-sized empire, Tigranes rather grandly began calling himself the “King of Kings” (Persian: shahanshah), although the title is further evidence that he left conquered monarchs to rule as vassals. Indeed, the Greek writer Plutarch (c. 45 - c. 125 CE) famously noted that Tigranes was always followed around by an entourage of four kings who acted as his servants. This comment may well have been based on a misunderstanding and the four men in question could well have been close counsellors who were also kings of their own respective regions but served the Armenian king as viceroys. Within the empire, conquered states might have kept their political apparatus but they were still obliged to pay tribute and contribute to Tigranes' army. Further, populations were relocated to reduce dissension and increase loyalty wherever required. Tigranes' title of King of Kings was then well justified and he made sure he looked the part as the historian V. M. Kurkjian here summarises:

Tigranes' public appearances were spectacular. He displayed all the pomp and magnificence becoming to a successor of Darius or Xerxes. Theoretically an equal of the gods, he clothed himself in a tunic striped in white and purple, and a mantle entirely purple. He always wore everywhere (even when hunting) a tiara of precious stones. Four of his vassal kings stood about his throne, and when he rode forth on horseback, they ran on foot before and beside him. (64)

Tigranes was noted as an admirer of Greek culture and the capital city he founded in 83 BCE, Tigranocerta (aka Tigranakert, meaning “Tigranes' foundation” but of uncertain location), was famously Hellenistic in its architecture. The city had impressive fortifications with the walls reaching a height of 22 metres and incorporating stables, such was their thickness. There were also such amenities as a Greek theatre, hunting parks and pleasure gardens. Tigranes was said to have forcibly relocated (a traditional figure of) 300,000 people to the new city, most of them from Cappadocia. Reflecting the cosmopolitan nature of the city, and the empire in general, the Greek language was likely used, along with Persian and Aramaic, as the language of the nobility and administration while commoners spoke Armenian. Persian elements continued to be an important part of the Armenian cultural mix, too, especially in the area of religion and the formalities of the court such as titles and dress.

Mithridates VI & Rome

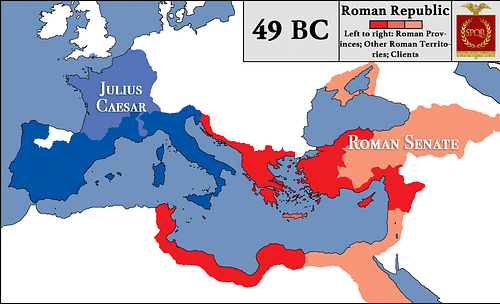

Tigranes then made his major political blunder and allied himself with Mithridates VI, the king of Pontus (r. 120-63 BCE) who was a great enemy of Rome with whom he had been waging war for over two decades. Admittedly, Tigranes had been married to Mithdridates' daughter Cleopatra since 92 BCE and, really, it seemed that whichever side Armenia chose - Rome or Parthia - the small kingdom caught between these great empires would always come off second best.

The Roman Republic saw the danger of such an alliance between the two regional powers, a suspicion which was confirmed by a joint Tigranes-Mithridates campaign against the Roman client state of Cappadoccia. The Romans responded by attacking Pontus and when Mithridates fled to the court of Tigranes in 70 BCE they asked for the former to be handed over. When Tigranes refused, the Romans invaded Armenia. Tigranes was defeated by a Roman army commanded by the general Licinius Lucullus, Tigranocerta was besieged and, after the betrayal of the Greek garrison, captured in 69 BCE. The Armenian king was, consequently, forced to abandon his conquests. The conquering Romans were amazed at the wealth of Tigranocerta, and that after Tigranes had already managed to spirit away his royal treasury.

Lucullus then moved to attack the important city of Artaxata (Artasat) but with winter coming on, his supply line dangerously thin and exposed, and even a mutiny amongst his own troops, the Roman general was forced to withdraw. Tigranes' army harried the retreating Romans using guerrilla tactics and although Lucullus captured Nisibis, he was recalled to Rome in 67 BCE. The respite would not last for long as the Roman Senate proved determined to stamp its authority on the region once and for all.

In 66 BCE another Roman army headed eastwards, this time led by Pompey the Great who had already won great acclaim. He had also celebrated two Roman triumphs; Pontus, Parthia and Armenia seemed as good a place as any to grab his third and a handsome load of booty to go with it. First, he attacked Pontus and sent Mithridates fleeing to the Black Sea. Next was Armenia's turn and here he was aided by Tigranes' traitorous third son, Tigranes the Younger.

Artaxata (now capital after Tigranocerta's demise) was attacked and, although it had resisted a Parthian siege the year before, quickly surrendered. Perhaps Tigranes did not want to see a repeat of the destruction at Tigranocerta and so there may not have been much actual fighting. Tigranes was now in old age and he seems to have bought off Pompey with the vast wealth he had been accumulating over a lifetime. Roman writers record that the Armenian king gave (or was made to give) 6,000 talents of silver to Pompey, 10,000 drachmas to each military tribune, 1000 drachmas for each centurion and 50 for each legionary. In these agreeable circumstances, Tigranes was permitted to retain the heartland of his kingdom trimmed of those territories he had acquired through conquest and with Sophene being given to his traitorous son - who incidentally got his comeuppance when he later insulted Pompey and so was marched to Rome for display in the general's third triumph there.

Armenia was, thus, made into a Roman protectorate but it is debatable if the empire of Tigranes, made up of such disparate and forcibly relocated populations and which was so loosely joined via tribute and coercion without much political apparatus, would have survived very long even without Roman interference. Henceforth, the Armenian state, although officially a friend and ally of the Romans, remained strategically important in the region and so was still a bone of contention between Rome and Parthia (and its successor, Sasanid Persia). Tigranes continued to rule most of Armenia quietly enough as a vassal state of the Roman Empire, acting as a useful buffer to the Parthians until his death c. 56 BCE aged around 85.

The Fall of the Artaxiads

Tigranes was succeeded by his son, Artavasdes II (r. c. 56 - c. 34 BCE) but the wheels were already coming off the Artaxiad success train. The Roman general Marcus Licinius Crassus obliged Artavasdes to support his disastrous campaign against the Parthians in 53 BCE and then, in 36 BCE, the region was again destabilised when yet another Roman general, this time Mark Antony, passed through, and the Armenians were, once more, asked to provide troops. The Romans were defeated again by their nemesis the Parthians. In 34 BCE Antony turned his attention to Armenia, moved against the Artaxiads and took Artavasdes captive to Alexandria where he would later be executed by Queen Cleopatra. There followed a merry go round of changes in sovereign over the next few decades, first a ruler supported by Rome, then by Parthia until the Artaxiad dynasty fell, replaced by the Arsacid (Arshakuni) dynasty and their founder, Vonon (Vonones), who took the throne c. 12 CE.

This article was made possible with generous support from the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research and the Knights of Vartan Fund for Armenian Studies.