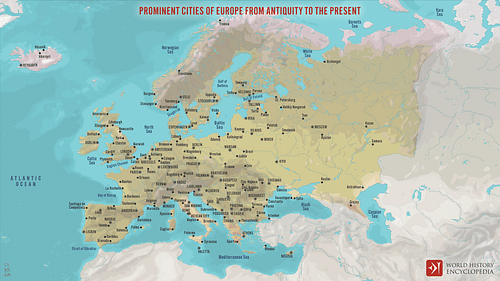

Europe is a continent forming the westernmost part of the land mass of Eurasia and comprised of 49 sovereign states. Its name may come from the Greek myth of Europa, but human habitation of the region predates that tale, going back over 150,000 years. It is the birthplace of Western Civilization and the modern concept of the state.

Scholars regularly refer to Europe as a peninsula bounded by the Arctic Ocean (north), Mediterranean Sea (south), and Atlantic Ocean (west) with Asia on its eastern border. Modern-day countries of Europe are usually classified according to the cardinal directions and include:

Northern Europe

- Denmark (including Faroe Islands and Greenland)

- Estonia

- Finland

- Iceland

- Ireland

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Norway

- Sweden

- United Kingdom (including England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales)

Southern Europe

- Albania

- Andorra

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Croatia

- Cyprus

- Gibraltar (part of the UK)

- Greece

- Italy

- Kosovo

- North Macedonia

- Malta

- Monaco

- Montenegro

- Portugal

- San Marino

- Serbia

- Slovenia

- Spain

- Turkey (west of the Bosporus)

- Vatican City State

Eastern Europe

- Belarus

- Bulgaria

- Czech Republic

- Hungary

- Kazakhstan

- Moldova

- Poland

- Romania

- Russia (west of the Ural Mountains)

- Slovakia

- Ukraine

Western Europe

- Austria

- Belgium

- France

- Germany

- Liechtenstein

- Luxembourg

- The Netherlands

- Switzerland

From the earliest hominins, who first appear in the region over 1 million years ago, the population spread, eventually developing diverse cultures from the prehistoric period to the classical, late antiquity, Middle Ages, early modern, to the modern era.

Prehistory

Archaeological evidence places Homo erectus in Europe c. 600,000 years ago during the Lower Paleolithic Period and Neanderthals by c. 150,000 years ago in the Middle Paleolithic Period. Although Neanderthals have routinely been discounted in the past as brutes, they actually developed an impressive culture which included cave art, grave goods (suggesting a belief in an afterlife), industry in making stone tools and hearths, textiles (clothing, cloaks, and blankets), boats, local and long-distance trade, the use of fire, and the development of music.

Homo sapiens arrived in Europe and replaced the Neanderthals some 50,000 years ago during the Upper Paleolithic Period. They continued to use caves as communal shelters, as the Neanderthals had, and created the impressive wall paintings at Chauvet Cave (dated to c. 32,000 years ago) and Lascaux Cave (dated to c. 20,000 years ago), both located in modern-day France. By this time, dogs had already been domesticated (roughly 32,000 years ago), prior to the First Agricultural Revolution of c. 10,000 BCE. Animal husbandry and agricultural developments led to semi-permanent and then permanent settlements as people moved away from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

During the Middle Neolithic Period megaliths were constructed, probably for religious purposes, suggesting closely-knit communities which could raise a significant workforce. Among the oldest megalithic sites is the Carnac Stones in Brittany, dated to c. 4500 BCE, and among the oldest megalithic tombs is Poulnabrone in Ireland, dated to c. 4200 BCE. The most famous megalithic site is Stonehenge in Wiltshire, England, dated to between c. 3000-2400 BCE, but many other sites are older including Newgrange in Ireland (3200 BCE) the Ness of Brodgar in Scotland (c. 3500 BCE) or the Mnajdra Temple Complex in Malta, dated to c. 3600 BCE.

The most famous example of the sort of Neolithic community that would have built these temples, tombs, and monuments is Skara Brae in Orkney, Scotland, dated to between c. 3100-2500 BCE. The Ancient Celts appear in the upper Danube region of Europe c. 1400 BCE. The Celtic Urnfield Culture was flourishing c. 1300 BCE, followed by the Hallstatt culture and the La Tène culture (c. 1200 to c. 450 BCE and c. 450 BCE to c. 50 CE, respectively). How the people of the region, Celts or those who came before them, referred to their land is unknown.

Name & Greek Colonization

The first appearance of Europe to designate the continent comes from Greece in the 6th century BCE, but it is unclear when the term was first used. The name may derive from the myth of Europa (known by the 8th century BCE when it is referenced in Homer's Iliad) in which the Phoenician princess is abducted by Zeus, king of the Greek gods, who, in the form of a bull, carries her off to Crete where she becomes queen of the first European civilization: the Minoan, which flourished from c. 2000 to c. 1500 BCE and, according to some scholars, created the first European written language.

This claim regarding Europe's name has long been challenged, however, from the time of Herodotus up to the present day. Herodotus writes:

As for Europe, not only does no one know whether it is surrounded by water, but the origin of its name is also uncertain (as is the identity of the man who named it), unless we say that it is named after Europa from Tyre, and that before her time the continent was after all as nameless as the other continents were. But it is clear that Europa came from Asia and never visited the land mass which the Greeks now call Europe; her travels were limited to going from Phoenicia to Crete. (Book IV.45)

Today, debate over the origin of the name continues. Theories include a Greek origin meaning "wide gazing" in reference to the breadth of the shoreline as seen from the sea or a Phoenician origin for the name meaning "evening" as in the place where the sun set. Europe was well known to the Phoenicians who regularly sailed as far north as Cornwall in Britain to trade in tin, but they only knew ports along the coastline, nothing of the interior and, according to Greek writers, Europe was viewed as a "dark continent" of mystery.

The Minoan civilization, like the Phoenicians, was a seafaring people with trade contacts throughout the Mediterranean. The Minoans competed with the Mycenaean Civilization (c. 1700-1100 BCE) in trade, and Minoan and Mycenean artifacts have been discovered in Anatolia, Egypt, Cyprus, the Levant, Mesopotamia, and Sicily, among other places. The Archaic Greeks (c. 800-480 BCE) continued to follow these trade routes but went further and established colonies from southern Italy to Anatolia up toward the Black Sea. Among these was the colony of Massalia (modern-day Marseille, France), the birthplace of Pytheas (l. c. 350 BCE) the geographer, who is said to have produced the work On the Ocean: the famous voyage of Pytheas exploring Europe c. 325 BCE.

Pytheas' work, detailing his travels to Britain, the northeastern coastline of Europe, and possibly Iceland and the Arctic Ocean among other areas, has not survived save through references and passages in the works of later writers, but it does not seem he explored Europe's interior, only the coast. To place European history in a global perspective, by c. 325 BCE, the Indus Valley Civilization had already risen and fallen, the Sumerians of Mesopotamia and the Assyrian Empire had come and gone, the Persian Empire had already fallen to Alexander the Great, and Egypt was at the tail end of its Late Period with the greatest of its achievements behind it. The pyramids of Giza were already over 2,000 years old by the time of Pytheas' voyage and Chinese culture had been established for over 4,000 years.

Greek colonization spread Hellenistic culture and values, establishing concepts such as Athenian democracy, forming the basis of Western Civilization. Permanent settlements increased trade – which led to further towns, cities, and ports – but, again, these communities were along the coast. The interior was unknown to the Mediterranean world until the rise of the Romans.

Roman Expansion

Rome was a small port on the banks of the Tiber River, founded in 753 BCE, which initially expanded through trade and came in contact with the Greek colonies to the south along modern-day Italy's coast. The Etruscan civilization, to the north, and the southern Greeks both significantly influenced early Roman culture and civilization. Rome developed between the 8th and 6th centuries BCE, deposed their last king in 509 BCE, and founded the Roman Republic that same year. By this time, the Romans had established themselves firmly through other colonies in Italy but expanded further during the Punic Wars (264-146 BCE) after which they controlled the regions of Spain, Portugal, and Gaul (modern-day Belgium and France) among others. Julius Caesar invaded Britain in 55 and 54 BCE but established no permanent presence there.

The Roman Republic became the Roman Empire under Augustus in 27 BCE, and under the Roman emperor Claudius, Britain was taken, beginning in 43 CE. By this time, the interior of regions like Spain and Gaul were well known to the Romans who established towns, ports, cities, religious sites, public baths, aqueducts, and built Roman roads throughout their territories as they had elsewhere. They proceeded with this same policy in Roman Britain and, although they met with considerable resistance – especially from the Picts of modern-day Scotland and from the Iceni queen Boudicca who led a major revolt against Rome in 60/61 CE – made Britain a province of the empire and held it until 410.

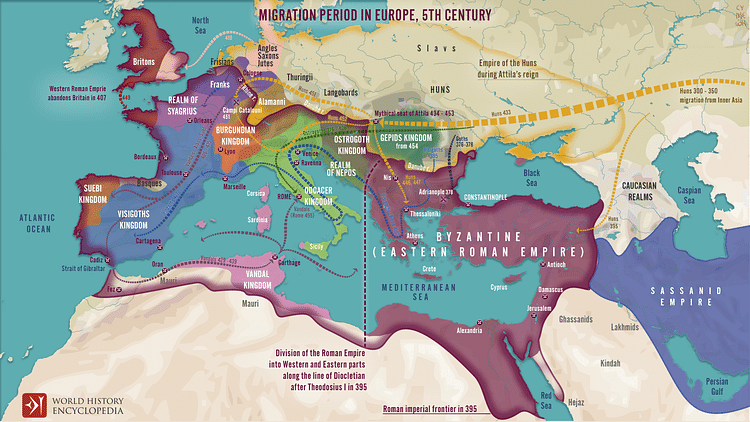

Roman expansion throughout Europe united formerly disparate regions through trade and a common cultural base. The Western Roman Empire was in decline, but the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire), with its capital at Constantinople, remained stable even during the so-called Migration Age when the Avars, Bulgars, Goths – Ostrogoths and Visigoths – Huns, Vandals, and others moved across Europe.

Christianity had been introduced to the region via the epistles and missionary work of St. Paul the Apostle in Greece in the 1st century and was legitimized in 313 by the emperor Constantine I through his Edict of Milan, decreeing religious tolerance. After Constantine’s conversion to Christianity, the new faith would eventually replace the older pagan religions of Europe and further provide cultural unity through a common religious belief system, especially after the Council of Nicaea of 325 established the orthodox vision.

Rise of the State, Church & Vikings

By the time the Western Roman Empire fell in 476, Christianity was well established in Europe. Kings such as Odoacer of Italy (r. 476-493) and Theodoric the Great (r. 493-526) considered themselves Christian kings as did Clovis I of the Franks (r. 481-511) and Alboin of the Lombards (r. 560-572). After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, leaders like these arose, and through military campaigns and treaties, they established kingdoms during the Early Middle Ages (476-1000) that would develop into states through the High Middle Ages (1000-1300) and Late Middle Ages (1300-1500) until European kingdoms had, more or less, become countries with a central government. These kings, and their subjects, adhered to the vision of the Roman Catholic Church which had split from the Eastern Orthodox Church in the Great Schism of 1054.

The medieval Church was understood as God's representative on earth and informed the lives of the people of Europe. Even though the common people did not understand Latin, the language of the Church, and did not always respect their parish priest, most people recognized its authority as the only path to redemption and eternal life in heaven. Those who did not conform were thought to spend eternity in hell or a certain time in purgatory where their sins were burned away through various tortures. Some people rejected the Church's vision, however, and these were branded as heretics and persecuted by the Church beginning with the Paulicians in the 7th-9th century.

The Church encouraged cultural and religious unity through these persecutions as it made clear there was only one true faith all people needed to follow. After the rise of Islam in the 7th century, the Church – and Christian European monarchs – found another 'enemy of the faith' to unify believers against, and this policy gained greater momentum after the Battle of Tours in 732 in which the Franks turned back a Muslim invasion of Europe.

Charlemagne (King of the Franks 768-814 and Holy Roman Emperor 800-814) became the champion of the Church, unifying the Franks and Lombards in 774 and suppressing European paganism through the Saxon Wars (772-804). The monastic orders of the Middle Ages developed further under Charlemagne, and the medieval monastery became an important center of learning and culture copying and preserving written works while also producing the famous illuminated manuscripts of Europe. A major threat to the monasteries, especially those along the coast, began in 793 through Viking raids in Britain, Francia, Ireland, and elsewhere, continuing up through the reign of Alfred the Great, King of Wessex (871-899), famous for his victories over the Vikings as well as encouraging literacy in Britain.

The Vikings settled in parts of Britain and France, some converting to Christianity and contributing to cultural developments, while others continued military campaigns up through 1066 when the Viking leader Harald Hardrada was defeated at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, ending the Viking Age. This was also the year of the Norman invasion of Britain under William the Conqueror (r. 1066-1087), the great-great-great-grandson of Rollo of Normandy (l. c. 860 to c. 930), the Viking chieftain who founded Normandy. The Norman conquest made French the language of the court, the upper class, and finance, and established French culture and customs throughout Britain, linking it with France and the other states of the European continent.

Renaissance & Reformation

The kingdoms and principalities of Europe had diverse languages, customs, and goals but were united – at least nominally – through religious belief and the authority of the Roman Catholic Church. In 1095, when Pope Urban II called the First Crusade to free the Holy Land from Muslim rule, people from all over Europe answered. Except for the first, the crusades between 1095-1270 ultimately failed in their objective but significantly altered the European cultural and political landscape. The crusades led to the rise of nation-states and monarchies supported by wider trade (and the need to protect trade routes), the establishment of more ports and trade centers, and the rise of the mercantile class. It also decreased the number of serfs working on the estate of nobles, weakening feudalism and empowering the monarchy.

The Black Death of 1347-1352 would decrease the population further, ending the feudal system, and also weakening the authority of the Church whose efforts to end the plague repeatedly failed. The Crusades and Black Death encouraged people to question the Church and the established order, and the rediscovery of ancient Greek literature and Roman texts led to the Renaissance and an increased focus on life on earth rather than what waited after death. The Renaissance encouraged the Protestant Reformation (1517-1648), spearheaded by Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) and enabled by the printing press of Johannes Gutenberg (l. c. 1398-1468), invented c. 1450. The printing revolution in Renaissance Europe allowed for the wide dissemination of Luther's – and then others' – works challenging the status quo and ecclesiastical authority. The printing press and the Protestant Reformation encouraged greater literacy and independence of thought, contributing to the Age of Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Conclusion

The Byzantine Empire fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 who then closed the Silk Road, ending European land trade with the East and encouraging greater maritime trade, which launched the Age of Exploration. The colonization of the Americas began in 1492 and was encouraged, not only by the European need to find alternative routes to the East but also by European history. The Crusades had established a paradigm of conquest in the name of Christianity while rivalry between Catholic and Protestant nations encouraged countries and religious communities to claim lands in the name of their respective faiths.

The Age of Exploration established European culture in the so-called New World between 1492-1620 with greater numbers of colonists arriving up through 1720 and even more afterwards into the early 20th century. The Dutch, English, and French – among others – also established colonies elsewhere, such as India, the Near East, and Africa – spreading European culture around the world. The benefits of imperialism and colonization went unquestioned by Europeans of the time but have been increasingly challenged since the mid-20th century. For better or worse, however, European history, culture, and political policies affected the development of a number of regions around the globe, influencing the establishment of many of the socio-political and religious paradigms of the modern world.