The Black Death was a plague pandemic that devastated medieval Europe from 1347 to 1352. The Black Death killed an estimated 25-30 million people. The disease originated in central Asia and was taken to the Crimea by Mongol warriors and traders. The plague then entered Europe via Italy, perhaps carried by rats or human parasites via Genoese trading ships sailing from the Black Sea.

The disease was caused by a bacillus bacteria, Yersinia pestis, and carried by fleas on rodents, although recent studies suggest human parasites like lice may well have been the carriers. It was known as the Black Death because it could turn the skin and sores black while other symptoms included fever and joint pains. With up to two-thirds of sufferers dying from the disease, it is estimated that between 30% and 50% of the population of those places affected died from the Black Death. The death toll was so high that it had significant consequences on European medieval society as a whole, with a shortage of farmers resulting in demands for an end to serfdom, a general questioning of authority and rebellions, and the entire abandonment of many towns and villages. The worst plague in human history, it would take 200 years for the population of Europe to recover to the level seen prior to the Black Death.

What Were the Causes of the Plague?

The plague is an infectious disease caused by a bacillus bacteria which is carried and spread by parasitic fleas on rodents, notably the brown rat. Other parasites, including those living on human skin, may also have spread the disease. There are three types of plague, and all three were likely present in the Black Death pandemic: Bubonic plague, Pneumonic plague and Septicemic plague. Bubonic plague was the most common during the 14th-century outbreak, causing severe swelling in the groin and armpits (the lymph nodes) which take on a sickening black colour, hence the name the Black Death. The black sores which can cover the body in general, caused by internal haemorrhages, were known as buboes, from which bubonic plague takes its name. Other symptoms are raging fever and joint pains. If untreated, bubonic plague is fatal in between 30 and 75% of infections, often within 72 hours. The other two types of plague - pneumonic (or pulmonary) and septicaemic - are usually fatal in all cases.

What Were the Symptoms of the Plague?

The terrible symptoms of the disease were described by writers of the time, notably by the Italian writer Boccaccio in the preface to his 1358 Decameron. One writer, the Welsh poet Ieuan Gethin made perhaps the best attempt at describing the black sores which he saw first-hand in 1349:

We see death coming into our midst like black smoke, a plague which cuts off the young, a rootless phantom which has no mercy for fair countenance. Woe is me of the shilling of the armpit…It is of the form of an apple, like the head of an onion, a small boil that spares no-one. Great is its seething, like a burning cinder, a grievous thing of ashy colour…They are similar to the seeds of the black peas, broken fragments of brittle sea-coal…cinders of the peelings of the cockle weed, a mixed multitude, a black plague like half pence, like berries…(Davies, 411).

How Did the Black Death Spread?

The 14th century in Europe had already proven to be something of a disaster even before the Black Death arrived. An earlier plague had hit livestock, and there had been crop failures from overexploitation of the land, which led to two major Europe-wide famines in 1316 and 1317. There was, too, the turbulence of wars, especially the Hundred Years War (1337-1453) between England and France. Even the weather was getting worse as the unusually temperate cycle of 1000-1300 now gave way to the beginnings of a “little ice age” where winters were steadily colder and longer, reducing the growing season and, consequently, the harvest.

A devastating plague affecting humans was not a new phenomenon, with a serious outbreak having occurred in the mid-5th century which ravaged the Mediterranean area and Constantinople, in particular. The Black Death of 1347 entered Europe, probably via Sicily, when it was carried there by four Genoese grain ships sailing from Caffa, on the Black Sea. The port city had been under siege by Tartar-Mongols who had catapulted infected corpses into the city, and it was there the Italians had picked up the plague. Another origin was Mongol traders using the Silk Road who had brought the disease from its source in central Asia, with China specifically being identified following genetic studies in 2011 (although South East Asia has been proposed as an alternative source and actual historical evidence of an epidemic caused by plague in China during the 14th century is weak). From Sicily, it was but a short step to the Italian mainland, although one of the ships from Caffa had reached Genoa, been refused entry, and docked in Marseilles, and then Valencia. Thus, by the end of 1349, the disease had been carried along trade routes into Western Europe: France, Spain, Britain, and Ireland, which all witnessed its awful effects. Spreading like wildfire, there were plague outbreaks in Germany, Scandinavia, the Baltic states, and Russia through 1350-1352.

Medieval doctors had no idea about such microscopic organisms as bacteria, and so they were helpless in terms of treatment, and where they might have had the best chance of helping people, in prevention, they were hampered by the level of sanitation which was appalling compared to modern standards. Another helpful strategy would have been to quarantine areas but, as people fled in panic whenever a case of plague broke out, they unknowingly carried the disease with them and spread it even further afield.

There were so many plague victims and so many bodies that the authorities did not know what to do with them, and carts piled high with corpses became a common sight across Europe. It seemed the only course of action was to stay put, avoid people, and pray. The disease finally ran its course by 1352 but would recur again, in less severe outbreaks, throughout the rest of the medieval period.

How Many People Died of the Black Death?

Although it spread unchecked, the Black Death hit some areas much more severely than others. This fact and the often exaggerated death tolls of medieval (and some modern) writers means that is extremely difficult to accurately assess the total death toll. Sometimes entire cities, for example, Milan, managed to avoid significant effects, while others, such as Florence, were devastated - the Italian city losing 50,000 of its 85,000 population (Boccaccio claimed the impossible figure of 100,000). Paris was said to have buried 800 dead each day at its peak, but other places somehow missed the carnage. On average 30% of the population of affected areas was killed, although some historians prefer a figure closer to 50%, and this was probably the case in the worst affected cities. Figures for the death toll thus range from 25 to 30 million in Europe between 1347 and 1352. The population of Europe would not return to pre-1347 levels until around 1550.

What Were the Consequences of the Black Death?

The consequences of such a large number of deaths were severe, and in many places, the social structure of society broke down. Many smaller urban areas hit by the plague were abandoned by their residents who sought safety in the countryside. Traditional authority - both governmental and from the church - was questioned for how could such disasters befall a people? Were not governors and God in some way responsible? Where did this disaster come from and why was it so indiscriminate? At the same time, personal piety increased and charitable organisations flourished.

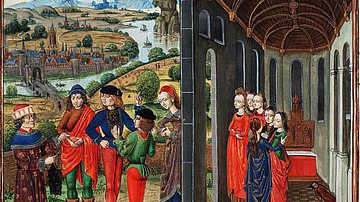

The Black Death, as its name suggests, was given a personification for people to help understand what was happening to them, usually being depicted in art as the Grim Reaper, a skeleton on horseback whose scythe indiscriminately cut down people in their prime. Many people were simply bewildered by the disaster. Some thought it a supernatural phenomenon, perhaps connected to the comet sighting of 1345. Others blamed sinners, notably the Flagellants of the Rhineland who paraded through the streets whipping themselves and calling for sinners to repent so that God might lift this terrible punishment. Many thought it an unexplainable trick of the Devil. Still others blamed traditional enemies, and age-old prejudices were fed leading to attacks on, and even massacres of, specific groups, notably the Jews, thousands of whom fled to Poland.

Even when the crisis had passed, there were now practical problems to be faced. With not enough workers to meet needs, salaries and prices soared. The necessity of farming to feed people would prove a serious challenge, as would the huge fall in demand for manufactured goods as there were simply far fewer people to buy them. In agriculture specifically, those who could work were in a position to ask for wages, and the institution of serfdom where a labourer paid rent and homage to a landlord and never moved on was doomed. A more flexible, more mobile, and more independent workforce was born. Social unrest followed, and often outright rebellions broke out when the aristocracy tried to fight these new demands. Notable riots were those in Paris in 1358, Florence in 1378, and London in 1381. The peasants did not get all they wanted by any means, and a call for lower taxes was a significant fail, but the old system of feudalism was gone.

After the major famines in 1358 and 1359 and the occasional resurgence, albeit less severe, of the plague in 1362-3, and again in 1369, 1374 and 1390, daily life for most people did gradually improve by the end of the 1300s. The general welfare and prosperity of the peasantry also progressed as a reduced population reduced the competition for land and resources. Land-owning aristocrats, too, were not slow to pick up the unclaimed lands of those who had perished, and even upwardly mobile peasants could consider increasing their landholdings. Women, in particular, gained some rights of property ownership they had not had before the plague. Laws varied depending on the region but, in some parts of England, for example, those women who had lost husbands were permitted to keep his land for a certain period until they remarried or, in other, more generous jurisdictions, if they did remarry then they did not lose their late husband's property, as had been the case previously. While none of these social changes can be directly linked to the Black Death itself, and indeed some were already underway even before the plague had arrived, the shock wave the Black Death dealt to European society was certainly a contributing and accelerating factor in the changes that occurred in society as the Middle Ages came to a close.