Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375) was an Italian poet, writer, and scholar. His most famous and influential work is the Decameron, completed by 1353, in which his ten characters present 100 tales of everyday life. The book covers all manner of secular themes and gives a vivid description of the Black Death, which had just hit Boccaccio's home region of Tuscany.

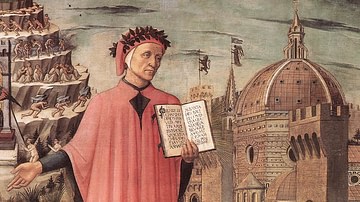

Writing in the vernacular and not Latin, Boccaccio, along with Dante Alighieri (1265-1321 CE) and Petrarch (1304-1374 CE), helped promote the use of Tuscan as a legitimate language for poetic literature. In the latter part of his career, Bocaccio turned more to Latin and studies of classical literature, composing an influential genealogy of Roman and Greek mythology, writing a biography of Dante and giving public lectures on that writer's works.

Early Life & Works

Giovanni Boccaccio was born in Tuscany (either in Certaldo or Florence) in 1313 CE and spent his childhood in Florence. His father was Boccaccio di Chellino, a Tuscan merchant, but nothing is known about his mother, except that she may have been French (it used to be thought he had been born in Paris). Around the age of 15, Giovanni was sent off to study business, finance, and canon law in Naples. With family connections to the rich Bardi family and access to the court in that city, he was introduced by scholars there to the early work of Petrarch. It was also here that he met and fell in love with Fiammetta, a woman who would be an important character in his literary work in the first half of his career, including the Decameron. Unfortunately for Giovanni, the Bardi went bankrupt and his father's finances suffered accordingly. Recalled to Florence around 1340 CE, Giovanni's career prospects took a serious downturn as the cold hand of poverty beckoned.

It was in Naples that Boccaccio had begun to write. His first known short poem was Diana's Hunt (Caccia di Diana) and there was, too, a longer poem, The Lovestruck (Filostrato). A lengthy prose work, also on a romantic theme, was The Love Afflicted (Filocolo). Boccaccio continued his literary ambitions in Florence and completed his Teseida, an epic poem set in ancient Greece, again with a romantic theme. Significantly, too, the Teseida was written in the Tuscan vernacular and not Latin. All of these works were written between 1335 and 1341 CE. Already, Boccaccio's style as a writer was becoming evident in his mix of medieval courtly love literature, pithy observations on contemporary life in Italy, and his bold and imaginative use of the Tuscan dialect.

Boccaccio's personal affairs are largely unknown in the middle of his life, except that he seems to have struggled financially and spent 1345-7 CE in Ravenna and then Forli before returning to Florence. Things picked up in 1350 CE when he was appointed an ambassador to the court of Romagna. The next year he served outside Italy as ambassador in Tirol, and in 1354 CE he performed the same role at the Vatican. He kept on writing throughout and produced numerous works of prose and poetry. These works are perhaps most notable for his innovative promotion of the ottava rima (where stanzas are formed of eight 11-syllable lines), then a form of poetry only used by lowly minstrels. It was to be his next work, though, that really established his name as one of the great medieval writers.

The Decameron

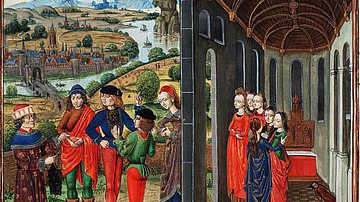

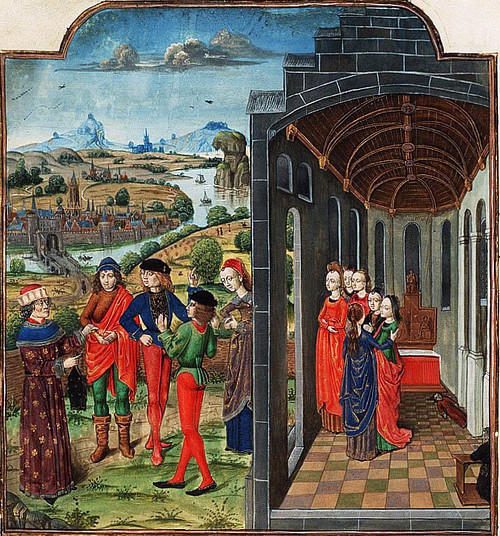

The Decameron (Ten Days) is a collection of tales Boccaccio compiled between c. 1348 and 1353 CE. In the work, ten young upper-class people are trying to escape the Black Death plague which has caused such chaos and disaster in their home city of Florence. Bocaccio gives a famous and lengthy description of the plague that had claimed the lives of his father, stepmother, and many friends. The description provides valuable contemporary information on the symptoms of the plague's victims and the general social consequences of a pandemic that devastated many European cities, towns, and villages.

[The plague] showed its first signs in men and women alike by means of swellings either in the groin or under the armpits, some of which grew to the size of an ordinary apple and others to the size of an egg (more or less), and the people called them gavoccioli (buboes). And from the two parts of the body already mentioned, in very little time, the said deadly gavoccioli began to spread indiscriminately over every part of the body; then, after this, the symptoms of the illness changed to black or livid spots appearing on the arms and thighs, and on every part of the body – sometimes there were large ones and other times a number of little ones scattered all around. And just as the gavoccioli were originally, and still are, a very definite indication of impending death, in like manner these spots came to mean the same thing for whoever contracted them. Neither a doctor's advice nor the strength of medicine could do anything to cure this illness…So many corpses would arrive in front of a church every day and at every hour that the amount of holy ground for burials was certainly insufficient for the ancient custom of giving each body its individual place.

(Decameron, trans. Musa & Bondanella)

The group of characters in the Decameron, made up of seven women and three men, travel to the safety of a secluded villa in the Tuscan town of Fiesole. Each member of the group is allowed to become king or queen for a day and dictate how the others will spend their leisure time that day. The king or queen also decides the theme of the ten, often comic stories each member must tell all the others. At the end of each day's tales, there is a climactic canzone or song. This happens over ten days and so the work contains 100 tales, which cover everything from commerce to adultery. Boccaccio is also presenting through these stories the way of life and attitudes of his characters, that is the well-to-do of Florence. In general, the portraits are favourable, and the mix of comedy and tragedy shows a group of people who follow certain conventions but who do not judge personal choices of lifestyle; the characters enjoy a bawdy tale but they are not without morals. Indeed, the work poses the tricky and age-old question of fiction writing: is the author presenting his own views in his fictional characters, in their fictional stories, in both or neither?

Full well my tears attest,

O traitor Love, with what just cause the heart,

With which thou once hast broken faith, doth smart.Love, when thou first didst in my heart enshrine

Her for whom still I sigh, alas! in vain,

Nor any hope do know,

A damsel so complete thou didst me shew,

That light as air I counted every pain,

Wherewith behest of thine

Condemned my soul to pine.

Ah! but I gravely erred; the which to know

Too late, alas! doth but enhance my woe.Save death no way of comfort doth remain:

No anodyne beside for this sore smart.

The boon, then, Love bestow;

And presently by death annul my woe,

And from this abject life release my heart.

Since from me joy is ta'en,

And every solace, deign

My prayer to grant, and let my death the cheer

Complete, that she now hath of her new fere.(Decameron, Canzone, Day Four, trans. J.M.Rigg)

As we view it today, a common theme of the stories in the Decameron, many of which derive from medieval folklore (from Europe and the Islamic world), is humans overcoming the vagaries of fortune and pressing on with their lives as best they can. This theme may account for its timeless appeal. At the time of publication, the structure, richness, and fast pace of the prose were unlike anything previously written, and composed in the Tuscan vernacular instead of the more usual Latin, it contributed to the growing popularity of using everyday speech in medieval literature. Indeed, it was listed in the 16th century CE by the influential scholar Pietro Bembo (1470-1547 CE) as the model for vernacular prose.

The work was extremely popular and this, along with other works by Boccaccio, influenced such writers as Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343-1400 CE) in his Canterbury Tales (published c. 1476 CE). In short, the Decameron became the standard against which all subsequent prose literature in Italy and abroad was judged. There were critics, too, such as those who thought some of the stories too vulgar, and it was put on the Catholic Church's list of forbidden books in the mid-16th century CE. As today, one can imagine that talk of the book's more scurrilous elements did nothing to dampen interest in it.

Classical Scholarship & Legacy

After completing Decameron, Boccaccio shifted his literary focus to more weighty matters. Indeed, he tended to minimise his achievement in the Decameron, preferring instead to follow the trends of what became known as Renaissance humanism, that is the study of classical texts and their relevance to contemporary life. This shift from fiction writing to scholarship was likely due to his correspondence and friendship with fellow Italian poet, scholar, and early humanist Petrarch (1304-1374 CE), whom he first met in 1350 CE. Boccaccio wrote in a letter to Petrarch that he had burned some of his own poetry after he compared it unfavourably to Petrarch's own work. The pair did not always agree on all matters. Boccaccio, for example, did criticise Petrarch for working with rulers of city-states who were politically against Florence. Boccaccio, too, was very concerned with creating a partly-fabricated Florentine tradition of new literature with Dante at its heart, a project of no interest to Petrarch who did not rate Dante very highly.

Boccaccio studied Greek and famously gave a series of public lectures in Florence's San Stefano di Badia church on the work of Dante from 1373 CE. This was the first time a non-classical writer was studied by university-level students. He also wrote a biography of Dante (1355 CE, revised 1364 CE) and a commentary on his Divine Comedy (c. 1374 CE).

Boccaccio's interest in the ancient world came to the fore with his collection of biographies on notable women from antiquity, Concerning Famous Women (De mulieribus claris), compiled from 1360 to 1374 CE. More significant than this work, though, was his Ancestry of the Pagan Gods (Genealogia Deorum Gentilium), completed by the 1360s CE (or perhaps earlier but subsequently revised). This work had 728 entries and, significantly, was the first text in the classical revival to give weight to Greek literature and language. The genealogy was much used by later Renaissance writers.

Suffering ill health and poverty in his final years, Boccaccio died in Certaldo on 21 December 1375 CE. He is buried in the Chiesa dei Santi Jacobo e Filipo (formerly SS. Michele e Jacobo) in that town. Boccaccio's works, as well as his searching out of Latin manuscripts 'lost' in obscure monastic libraries, his interest in human affairs in Decameron, his innovation using ottava rima, and his promotion of the vernacular in prose, were all reasons why Boccaccio came to be regarded as one of the founders of Renaissance humanism and one of the 'Three Crowns of Florence' (the others being Dante and Petrarch).