Geoffrey Chaucer (l. c. 1343-1400 CE) was a medieval English poet, writer, and philosopher best known for his work The Canterbury Tales, a masterpiece of world literature. The Canterbury Tales is a work of poetry featuring a group of pilgrims from different social classes on a journey to the shrine of St. Thomas Becket in Canterbury who agree to tell each other stories to pass the time. Chaucer was well acquainted with people from all classes, and this is evident in the details he chooses as well as the accents employed, how the people dress, and even their hairstyles. The Canterbury Tales have therefore been invaluable to later scholars as a kind of snapshot of medieval life.

Chaucer was a prolific writer, creating many other fine works which have been overshadowed by The Canterbury Tales. None of his pieces were technically published during his lifetime as that concept had not yet been invented. His works were hand-copied by scribes who admired them and either sold or shared them. Chaucer did not make a living from his writing, as his occupations and salaries from court records attest, but was honored for his poetry by noble patrons in other ways. His major works are:

- The Book of the Duchess (c. 1370 CE)

- The House of Fame (c. 1378-1380 CE)

- Anelida and Arcite (c. 1380-1387 CE)

- The Parliament of Fowls (c. 1380-1382 CE)

- Troilus and Criseyde (c. 1382-1386 CE)

- The Legend of Good Women (c. 1380's CE)

- The Canterbury Tales (c. 1388-1400 CE)

Chaucer was multilingual, fluent in Italian, French, and Latin and translated works from French and Latin to English (The Romance of the Rose from Old French to Middle English c. 1368-1372 and Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy from Latin in the 1380s CE). He also established Middle English as a respectable medium for medieval literature (previously, works were written in either French or Latin) and coined many English words used in the present day (such as amble, bribe, femininity, plumage, and twitter, among numerous others) as well as inventing the poetic form of the Rime Royal. He was praised by contemporaries for his lyrical skill and imaginative power, and his style and choice of subject matter influenced the writers of his time and all those who came after him. He is commonly regarded as the Father of English Literature.

Early Life & Travels

Geoffrey Chaucer was the son of John Chaucer, a wealthy vintner (winemaker and seller) and his wife Anne. The family was originally from Ipswich (northeast of London) but Robert Chaucer (Geoffrey's grandfather) moved to London in the early 1300s CE. Chaucer received a good education. Chaucerian scholar Larry D. Benson notes how there were three schools near the Chaucer home on Thames Street, among them St. Paul's Cathedral, which taught Latin, theology, music, and classical literature among the standard medieval curriculum. After attending one of these schools, probably St. Paul's, Chaucer got his first job at around the age of 13. In 1356 CE, Chaucer was given the position of page to Elisabeth de Burgh, Countess of Ulster.

The countess' household account book for 1357 CE mentions Chaucer by name and lists clothing purchased for him and “necessaries at Christmas” (Benson, xvii). As part of the countess' retinue, Chaucer would have traveled around the country frequently as she paid visits to other nobility and participated in various festivals and pageants. This position, which he could have only held as a member of a wealthy and respected family, was his introduction to court life. It would also introduce him to John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (l. 1340-1399 CE) who would later become his best friend and patron.

In 1359 CE, Chaucer was part of an expedition to France led by Elizabeth de Burgh's husband Lionel under the command of King Edward III (r. 1327-1377 CE) in one of the English offensives of the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453 CE). The goal was to take the city of Rheims where French kings were traditionally crowned and make Edward III king of France as well as England. Chaucer was involved in the Siege of Rethel near Rheims when he was captured in early 1360 CE, and Edward paid 16 pounds for his release. Chaucer continued in military service until October 1360 CE when he carried letters from Edward back to England from Calais. Chaucer's whereabouts between 1360-1366 CE are unknown, but it is believed he was traveling either in the king's service or on pilgrimage.

Court Life, Marriage, & The Book of the Duchess

By September 1366 CE, Chaucer was back in England and married to Philippa Roet, and in 1367 CE he is recorded as a member of the royal household holding with the title of esquire and valet. Benson describes Chaucer at this time as being “one of a group of some forty young men in the king's service, not personal servants, but expected to make themselves useful around the court” (xviii). Philippa and Geoffrey both received royal annuities as Philippa was a lady-in-waiting attending female members of the court.

During this time, Chaucer began to write poetry in French, experimenting with various forms. He was sent to France a number of times on official court business and may have also traveled in Italy. His relationship with John of Gaunt was by this time a sincere friendship. John's wife Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster, died in September 1368 CE, and he fell into a period of deep grief mourning her loss. Chaucer wrote his first major work, The Book of the Duchess, in her honor and as a means of consoling his friend.

The Book of the Duchess is written in the form of a poetic genre known as the high medieval dream vision in which a narrator begins by relating a profound personal problem (death of a loved one, struggles with one's religious faith), tells of a dream which confronts this problem, and concludes with how the dream resolved the narrator's conflict.

In The Book of the Duchess, Chaucer's narrator opens the piece lamenting how he cannot sleep, has not slept in years, ever since the woman he loved left him. The narrator is reading a book about two lovers parted by death, falls asleep, and dreams he is in a strange forest where he meets a black knight. The knight is in mourning over a lost love, and the narrator listens to his story of their happy life together and then of his grief over her recent death. The narrator wakes and tells the reader how amazing the dream was and how he will now write it down before it is forgotten.

The poem deals with a central concern of the poetic genre of courtly love, a popular tradition of medieval France dealing with romantic relationships, which asked (among other questions) which was worse, to lose one's love to death or to infidelity. It was decided infidelity was worse because, when one's lover cheated or left, they took away the past and the future by ruining memories and destroying the relationship, while when one's lover died, one could still cherish past memories. Further, an unfaithful lover chose to leave; one who died was taken against their will.

Chaucer never provides an answer in The Book of the Duchess one way or another on this concern. His narrator has lost a love to infidelity while the knight has lost his to death. Chaucer leaves it up to the reader to decide whose situation is more painful, but his narrator, consoling a symbolic John of Gaunt character, sympathizes fully with the black knight's grief and subtly inverts the courtly love tradition by suggesting that losing a loved one to death is worse than infidelity because there is no chance of reconciliation.

John of Gaunt appreciated the work as evidenced by his grant of a life annuity of 10 pounds to Chaucer “in consideration of the services rendered by Chaucer to the grantor” (Benson, xix). Chaucer was then sent to Italy by the king on some official business which brought him to Florence where he may have met the great Italian poets Petrarch and Boccaccio or, if not, was certainly influenced by their work as well as Dante's. He was probably working on other poems at this time but there is no way of knowing which ones. After his return from Italy, however, he was awarded a special grant by Edward III of a gallon of wine daily for life, and it is supposed this was an award for a poem Chaucer had written for the king, especially so since it was given on St. George's Day when artistic achievements were rewarded.

Other Major Works

In 1374 CE, Chaucer was appointed controller of customs, overseeing exports and regulating taxes at the customs house of the port of London. Even though the job kept him busy, he made time to write and composed his House of Fame, Parliament of Fowls, and Troilus and Criseyde during his time as well as translating Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy. Benson notes that “Chaucer was most prolific as a writer when he was apparently most busy with other affairs” (xxi).

The House of Fame is another dream vision in which Chaucer-as-narrator is abducted by an eagle with gold wings and brought to the House of Fame which is the home of all sound. In the House, Chaucer sees Fame, a woman of many eyes, ears, tongues, awarding fame and infamy to various people throughout history. The concept of fame is characterized as fleeting and dependent on what others say about a person rather than the individual's actual merits. After watching Fame at work for some time, Chaucer is led from the House by a man who brings him to another building, a spinning house in a valley, which symbolizes rumor and gossip and how quickly they influence fame. Inside the house is a huge crowd all talking at once but who fall silent at the approach of a man of great authority, and after this line, the poem breaks off and was never finished.

The Parliament of Fowls is the first mention of St. Valentine's Day in literature and, according to some scholars, Chaucer may have actually invented the holiday in this poem. Working within the dream vision form again, Chaucer wrote the piece in Rime Royal (stanzas of seven lines in iambic pentameter) which gives it a brisk, upbeat tone. The poem begins with Chaucer-as-narrator lamenting the difficulties of love – “the life so short, the craft so long to learn” (line 1) – refers to the “craft” or art of love which the narrator has not mastered. While reading a book to try to learn it better, he falls asleep and a mystical guide appears, leads him through a dreamscape and the Temple of Venus, and brings him to the court of Dame Nature who is presiding over the birds' mating ritual.

Before the “lesser birds” can choose a mate, the great eagles go first, but three tercel eagles all want the hand of a single formel. None of them will back down, and none of the other birds can do anything until the matter is decided and so the lesser birds and the eagles begin a parliamentary debate. Dame Nature moderates and finally ends the argument, asking the formel which eagle she would prefer. The formel answers she wants none of them and will happily wait until next year to choose a mate. The other birds are then free to choose theirs, and all begin singing joyously in celebration of love. The narrator is glad for the birds, but when he wakes from his dream, he realizes he is no closer to understanding love than he was before and returns to reading.

This theme of romantic love and its difficulties is dealt with at length in Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde, whose form and matter are both influenced by Boccaccio's Il Filostrato. The backdrop of the story is the Trojan War and the main characters a Trojan warrior and a noble maiden. In the beginning of the poem, Troilus makes fun of love and lovers as foolish time wasters and so Cupid, god of love, strikes him with an arrow, causing him to fall desperately in love with Criseyde. Her uncle Pandarus assists Troilus in courting Criseyde and, since Troilus has always been so adamant about the foolishness of love, he wants to keep their relationship secret and Pandarus helps in this as well. When the Greeks capture an important Trojan warrior, Antenor, Criseyde's father, Calkas, suggests they exchange Criseyde for him as she is single and unattached to anyone in the city. Troilus cannot say anything without revealing his relationship and so Criseyde goes to the Greek camp. She promises Troilus she will escape and return to him in ten days, but once in the camp, she sees that is impossible and accepts the overtures of a Greek warrior Diomedes, fairly quickly becoming his lover. Heartbroken, Troilus goes into battle and is killed. As he floats up toward heaven, he looks back on his life and all the situations he took so seriously and laughs.

Troilus and Criseyde was so popular that her character entered English as the idiom “false as Criseyde” in reference to an unfaithful woman or a statement of questionable truth. In Chaucer's next work, The Legend of Good Women, he claims he was instructed by Queen Alceste, wife of the god of love, to make amends to women for his depiction of Criseyde. He is required to write a number of tales showing strong, powerful women who accomplished great deeds such as Cleopatra and Dido. Chaucer completed ten stories but, in his prologue, makes clear he was supposed to write more. The poem was never completed, and scholars believe this is because the author lost interest in it.

The Canterbury Tales

Chaucer worked at the customs house for twelve years during which time, in addition to writing the above works, he went on a number of errands described in court records as “secret business of the king”. C. 1385 CE, he received his first international tribute as a poet by way of a ballad to him from the leading French poet of the day, Eustace Deschamps (l. 1346 - c. 1406 CE), which was all the more impressive because Deschamps hated the English and dedicated many of his poems to mocking and criticizing them. Deschamps was a significant influence on Chaucer's early works, especially his shorter poems, and the tribute must have meant a great deal to him. At the same time, English writers began praising Chaucer's work, notably John Gower (c. 1330-1408 CE), who became one of Chaucer's closest friends.

He may have begun The Canterbury Tales while still in London, but more likely it was after he had left his position at the customs house and moved to Kent. In the General Prologue of the poem, in which he introduces his characters, Chaucer-as-narrator relates how the pilgrims, setting out from the Tabard Inn at Southwark for Becket's shrine at Canterbury, will each tell two stories on the way and two coming back; the one whose story is judged best wins a free meal at the Tabard upon their return. The completed work would then have been comprised of 120 tales, but Chaucer only wrote 24, which is why the piece is considered unfinished.

The Canterbury Tales is Chaucer's masterpiece, written at the height of his poetic skill. The work is by turns satiric, tragic, ribald, and comic, varying from tale to tale. Chaucer-as-narrator appears as a young, naive member of the group who describes all the others without criticism; Chaucer-the-author, of course, critiques all of them subtly or directly through his descriptions. He was especially critical of the Church of his time, pointing out the hypocrisy and greed of the clergy through characters such as his Pardoner who is little more than a con man.

Conclusion

From 1386 CE on, Chaucer held a number of important and highly-paid positions such as Justice of the Peace, a member of Parliament, Clerk of the King's Works, and Deputy Forester of the Royal Forest. He was also a member of the Kent Peace Commission and, as always, in service to the crown on various matters which are not specified in the records.

Chaucer was still at work on The Canterbury Tales when he moved back to London in the 1390's CE. He rented a home near Westminster Abbey, where he died in October of 1400 CE. He was buried in the abbey because he was a member of the parish, but his grave would mark the first of the famous Poet's Corner of Westminster Abbey where many great writers and poets have been buried or memorialized since.

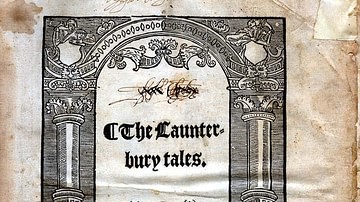

The Canterbury Tales was first published by William Caxton in c. 1476 CE in London, and the work became a bestseller. Even in Chaucer's lifetime, though, scribes had been copying and sharing his works so the claim that he only became famous as a writer after his death is untenable. By c. 1500 CE, Chaucer's reading audience had grown wider and he was hailed by critics for his poetic skill and vision. In 1556 CE, a marble monument to him was erected on his gravesite by the local poet Nicholas Brigham citing Chaucer as the “bard who struck the noblest strains” in poetry and his reputation has only grown in the centuries since.