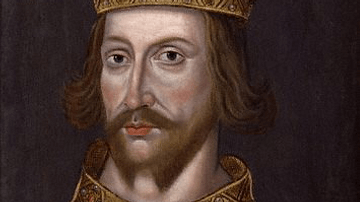

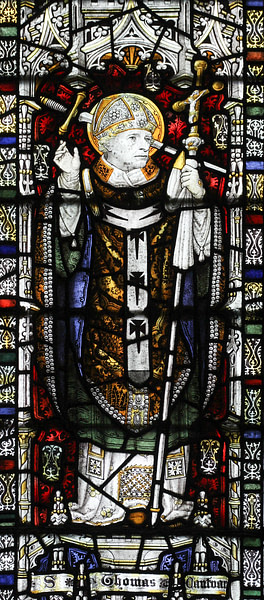

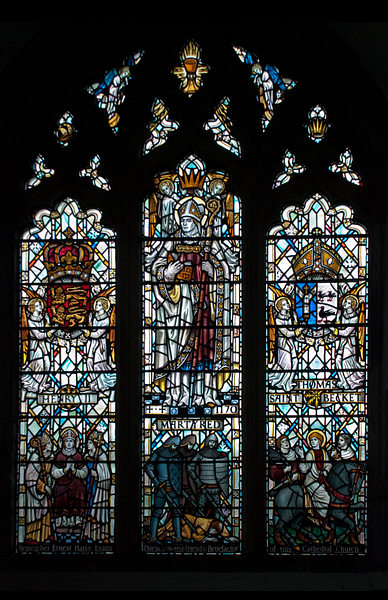

Thomas Becket (aka Thomas á Becket) was chancellor to Henry II of England (r. 1154-1189) and then archbishop of Canterbury (1162 to 1170). Thomas repeatedly clashed with his sovereign over the relationship between the Crown and Church, particularly the right of Church courts to try clerics. Thomas was murdered by four knights in Canterbury Cathedral on 29 December 1170.

The outrage which resulted from Becket’s death amongst members of the clergy and nobility caused Henry to back down. Although he had given no direct order to murder Thomas, the king had to perform a penance for his connection to the whole sorry affair. Thomas Becket was made a saint by the Pope in 1173 and has been henceforth regarded as a martyr for defending the rights of the Roman Church. Consequently, he is sometimes referred to as Saint Thomas of Canterbury.

Early Life

Thomas Becket was born c. 1118, the son of a rich wine merchant based in Cheapside, London who prospered thanks to his contract to supply the royal court. The young Thomas was sent to study at the Augustinian monastery of Merton priory and then for various incompleted spells in Paris, Bologna, and Auxerre. Thomas' first job of note was as a clerk to the archbishop of Canterbury in 1146. In 1152 he became the archdeacon of Canterbury Cathedral. He must have impressed in these offices because Henry II made Thomas the chancellor from January 1155. Thomas made the chancellor position his own and transformed a relatively minor post into a chief minister of all the other government ministries. The chancellor even found time to act as tutor to Henry the Young King (l. 1170-1183), the son of Henry II. The prince, and a few other royals, lived with Thomas until they attained their knighthoods. Henry II and Thomas became good personal friends and often went hunting and hawking together.

Rather ironically, considering Thomas Becket's legacy as a defender of the Church, the chancellor spent a lot of his time trying to extract as much money as possible from it to help pay for Henry II's military campaigns. The chancellor became extremely unpopular with bishops and abbots across England and his reputation did not improve when they saw how rich he became personally. The chancellor's extravagance was most evident on his trip to Paris in 1158 when he travelled with 250 servants and 24 changes of clothes in his wardrobe. Back in England, thanks to the perks of his job and regular gifts of lands from the king, Thomas came to own vast estates and a personal household army of 700 medieval knights. Loving the high life, Thomas once infamously ate a dish of rare eels costing an astronomical 100 shillings, enough to buy a small herd of cows.

King vs. Archbishop

Henry II sought to reaffirm the power of the monarchy in its relationship with the medieval Church. The Church in England had always been separated from the state but kings had traditionally had a say in who occupied the top job of the archbishop of Canterbury. Accordingly, Henry II appointed his chancellor Thomas Becket as the new archbishop of Canterbury in June 1162. This was something of an unusual move as Thomas was not even in major orders and seemed to be living a life very far from one we would imagine ideal preparation for a role in the clergy. It is likely that Henry thought Thomas, already proven as no particular friend of the Church, would help him in his attempt to limit the benefits and rights of the clergy. A particular point of contention between the Crown and Church was the latter's claim that all disputes and crimes (even serious ones such as theft, rape, and murder) that involved Church lands and members of the clergy should be dealt with only by ecclesiastical courts either in England or, on higher appeal, the Pope in Rome. There was, too, a great difference in the punishment a clergyman could expect - penance or defrocking at worst - compared to a layman under the king's justice system - fines, mutilation, or execution. As it turned out, Thomas Becket, although initially reluctant, took to his new role with characteristic gusto and completely changed his way of living and outlook. Henry II had made one of the most serious mistakes of his reign.

There was first a transitional period when the new archbishop upset a few monks and bishops by his continued wearing of secular clothes and he made several enemies through his passion for argument. Next, Thomas resigned as chancellor, stating he could not do both jobs properly at once. Then, seeming to settle fully into the role by around 1163, Thomas got rid of all the fine furniture, gold plate, and fancy clothes and settled down to a life of study, prayers, and alms-giving. This change in character has never been explained by contemporaries and has puzzled historians ever since. The most reasonable explanation seems to be a combination of Thomas wanting to do his job just as well as he had performed for the state as an excellent chancellor, and perhaps, too, a genuine religious conversion. Whatever, the reasons, Thomas became the great defender of the Church's rights and liberties. The archbishop insisted on absolute loyalty from his bishops as he resisted the king's attempts to limit the powers of the Church and extract taxes from its lands and interfere in appointments and punishments. Thomas regarded the king's proposals as a direct threat to the independence of the Church and to the Pope's position as the leader of the Christian world (although the Pope himself actually suggested a compromise between the two parties). Neither side would budge and Thomas even began a smear campaign against certain members of the royal court, denouncing them as immoral. Henry did the same and spread accusations that Thomas had been guilty of gross corruption during his time as chancellor. The clash of ideas was now a personal duel.

Matters came to a head in January 1164 when Henry called a meeting of all the important people in England. Barons, royal officials, and high Church figures all gathered at Clarendon in Wiltshire where the king sought to reform the judicial system and establish the principles of Common Law. The king made Thomas and his bishops swear to observe the laws and customs of the land. These rather vague points were then listed in the 16 articles of the Constitutions of Clarendon but were all written in favour of the monarch and detrimental to the liberties and finances of the Church. As a result of this obvious bias, Thomas revoked the Constitutions and his oath of loyalty. Thomas did not have very much support from within his own church, though, as the clergy knew full well that the consequences of going against such a powerful monarch as Henry II would be dire. A summit of nobles at Northampton in October 1164 found Thomas guilty of contempt of royal authority and the archbishop was consequently obliged to flee to the safety of a Cistercian monastery in Potigny, France. Henry confiscated all of Thomas' estates.

Return From Exile & Murder

Six years later and after intervention from the Pope, Thomas returned to England in early December 1170 and a reconciliation with his king. Thomas was asked to recrown Henry the Young King after the Pope had decided the original coronation, in which the Archbishop of York had performed the ceremony, was void. However, neither Thomas nor Henry II had really changed their positions and further clashes became inevitable. Almost immediately after his return, Thomas began to suspend or excommunicate those bishops who had not supported him against the king. When an exasperated Henry remarked 'Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?' four medieval knights: William de Tracey, Richard le Breton, Hugh de Morville, and their leader Reginald FitzUrse, took this as a literal order and so they searched out Thomas to make sure some serious harm came to him.

Confronting the archbishop while he was having dinner at home, the four knights presented Thomas with their charges and insisted he accompany them back to Westminster. Thomas refused and, as members of his household rallied in support, the knights were forced to withdraw, but not before they arrested Thomas' seneschal William FitzNigel.

A short while after this fracas, Thomas was again confronted by the four knights, who by now seemed to be drunk, in Canterbury cathedral while a service was ongoing. Once again the knights insisted Thomas accompany them to Westminster and once again the archbishop refused. As the knights brandished their swords, most of the congregation fled the cathedral in panic. The knights then grabbed Thomas but he stubbornly clung on to a column. One knight raised his sword to strike the archbishop but a clerk, Edward Grim, leapt in between the two. Grim's arm was badly slashed and Thomas received the remainder of the blow on his head. More blows rained down on the archbishop who was said to have exclaimed in defiance: 'For the name of Jesus and the protection of the church, I am ready to embrace death' (quoted in Barratt, 62). In a frenzy of sword slashes which caused one knights' weapon to shatter against the stone flooring, Thomas Becket was butchered on 29 December 1170.

A Penitent King

The murder shocked the establishment and caused the king to lie low for a while in Ireland. Fortunately for Henry, papal legates eventually found the king innocent of being directly involved in Thomas' death and so he was saved from excommunication. However, in July 1174, Henry was obliged to serve penance for his involvement as a contributory factor to the crime. The penance involved walking barefoot to the archbishop's tomb in the cathedral in which he was murdered, where bishops and monks armed with branches then performed a penitential flogging of the shirtless king. Henry then had to spend the night on the cold stone flagstones upon which the archbishop's blood and brains had been spilt. Another blow to Henry was the Pope's insistence he retract all parts of the Constitutions of Clarendon. The Church had won for the time being but its powers would be nibbled away by Henry's successors for the rest of the Middle Ages.

One of the four murdering knights, Sir Hugh de Morville, Lord of Westmoreland, was disinherited by the king and obliged to visit in person Pope Alexander III (r. 1159-1181). The Pope then instructed all four of the knights involved that the only way to achieve forgiveness for their dastardly deed was to go on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Sir Hugh may have been a member of the entourage of Richard I of England (r. 1189-1199) that embarked on the Third Crusade (1189-1192).

Thomas Becket, meanwhile, became a martyr figure against tyranny. Soon miracles were attributed to the dead archbishop, and his tomb became a hotspot for pilgrims. Another legacy of the Becket affair was the outrage and shock caused by his death galvanised many nobles to turn against Henry II. The barons, along with Henry's son and wife Eleanor of Aquitaine, launched an 18-month rebellion against the king. The rebellion was quashed by the end of 1174, the king having wisely invested in castles to protect his control of the kingdom.

Legacy & Legends

After Pope Alexander III had made Thomas Becket a saint in 1173, Saint Thomas of Canterbury soon became a powerful name to invoke for divine assistance. For example, when Queen Eleanor of Provence (1223-1291) was near to giving birth, her husband Henry III of England (r. 1216-1272) had the saint's tomb surrounded by 1,000 candles and invoked his assistance. The child was indeed born safely. In the 14th century, the archbishop was not forgotten. Geoffrey Chaucer (l. c. 1343-1400) wrote his famous work The Canterbury Tales (c. 1388-1400) which is a compendium of stories all of which have their characters on a pilgrimage to Thomas Becket's tomb in Canterbury Cathedral. Indeed, by that time, the city was one of the most popular pilgrimage sites in medieval Europe. Thomas became the patron saint of England for a while, a crusading order was founded in his name at his birthplace in Cheapside, and London Bridge was rebuilt in stone as a mark of remembrance to the martyr.

The long shadow of the saint was further seen at the coronation of Henry IV of England (r. 1399-1413) in Westminster Abbey in 1399. Sacred oil believed to have been miraculously given to Thomas by the Virgin Mary had only recently been discovered hidden away in one of the darker corners of the Tower of London's cellars. The oil, whatever its real origin, was a useful add-on in Henry's search to legitimise his usurpation of the throne from Richard II of England (r. 1377-1399). The oil was used in several coronations thereafter, and it was said in medieval times that it would guarantee the anointed monarch success in regaining lost territories in France. As it turned out, no monarch ever managed such a feat.

Thomas even popped up in unusual places. The watergate structure of the Tower of London became known as Saint Thomas' Tower. The saint was once claimed by workers rebuilding the outer wall of the Tower of London to have appeared as a ghost there, the first of many to be spotted haunting the Tower. Perhaps Thomas had been inspecting the progress of the building he had once supervised as Constable of the Tower in the 1150s. The stature of Thomas Becket just kept growing as his defiance inspired subsequent archbishops, and he became a figurehead for those who saw the benefits of limiting the power of the monarch. It was for this reason that Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547) destroyed Thomas' shrine in Canterbury in 1538 and forbade his cult. History, though, would not forget.