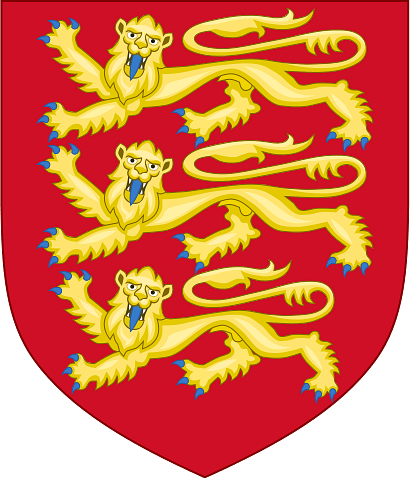

Richard I of England, also known as Richard the Lionheart (Cœur de Lion), reigned as king of England from 1189 to 1199. The son of Henry II of England (r. 1154-1189) and Eleanor of Aquitaine (c. 1122-1204), Richard was known for his courage and successes in warfare, but he became so busy with the Third Crusade (1189–1192) and then the defence of English-held territory in France, that he would only spend six months of his reign in England. A legend in his own lifetime, famed both for his military leadership and utterly ruthless approach to warfare, Richard the Lionheart has become one of the greatest figures in European history, and his arms of three lions are still used by the British royal family today. Following his death in battle at Chalus in France, Richard was succeeded by his younger brother King John of England (r. 1199-1216).

Early Life & Succession

Richard was born on 8 September 1157 in Beaumont Palace, Oxford, as the third son of King Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine, former wife of King Louis VII of France (r. 1137-1180). Richard's education involved a good dose of chivalric medieval literature thanks to his mother's interest in the subject. Poetry was another favourite pastime and the king composed his own poems in both French and Occitan (a French dialect commonly used in romances). The young prince was said to have been a tall, blue-eyed, handsome fellow with reddish-blonde hair and he was already noted for his courage.

This was a period of troubled and complex relations between England and France, and Richard, whose family had been the principal cause, would be involved in two rebellions against his father. The first bid to topple the king came in 1173 when Richard, his brothers Henry and Geoffrey, the Count of Brittany (b. 1158), and William the Lion of Scotland (r. 1165-1214) all conspired to join forces, almost certainly a pact orchestrated by Eleanor of Aquitaine. Eager to increase their own domains at the expense of the English crown, the murder of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket (1162-1170), in his own cathedral in 1170 proved a rallying point, given Henry's alleged involvement in this shocking crime. Aged just 15, Richard had been knighted by Louis VII, another interested party in seeing the downfall of Henry, and dispatched on a campaign to invade eastern Normandy, then under the English crown. The rebels failed to oust Henry II thanks to his loyal barons and many castles, but Richard was pardoned after he swore allegiance to his father. Eleanor, in contrast, was imprisoned for her troubles. This was not the end of the affair, though, as Henry struggled to keep a grip on his kingdom in his final years.

Richard, as a prince, held the titles of the Duke of Aquitaine and Count of Poitou (both in France and arranged by his mother), and he cemented his growing reputation as a gifted field commander and besieger of castles by quashing a revolt by the barons of Aquitaine. His taking of the once-thought impregnable castle of Taillebourg in 1179 was an especially splendid feather in his prince's coronet. Less splendid were the tales of his ruthless treatment of prisoners and forced prostitution of captured noblewomen. Still, despite his successes, Richard wanted more. Then, the fates intervened and Richard's chief rival for the throne of England, his elder brother Henry the Young King (b. 1155) died in June 1183. Henry II had gone so far as to make his son king-designate in 1170, but the young Henry's death from dysentery scuppered the king's neatly arranged succession plans. In addition, his other brother Geoffrey died in an accident at a medieval tournament on 19 August 1186. Richard was now in prime position to become the next king of England, but he was not prepared to simply wait for nature to take its course.

Richard again challenged his father in 1188-9 when he and his younger brother John formed an alliance with Philip II, the new King of France (r. 1180-1223). The rebellion was again supported by Eleanor, and the war included the legendary episode in which the famous medieval knight Sir William Marshal (c. 1146-1219) fought Richard, had the prince at his mercy but chose to kill his horse instead. Notwithstanding their rivalry, or perhaps in gratitude for his chivalry, Richard later gave William Chepstow Castle, as had been promised him by Henry II. Losing control of both Maine and Touraine, Henry eventually agreed to peace terms which recognised Richard as his sole heir. When the king died shortly after, Richard was crowned his successor in Westminster Abbey on 2 September 1189. Also part of his kingdom were those lands in France still belonging to his family the Angevins (aka Plantagenets): Normandy, Maine, and Aquitaine. Richard refused to give John Aquitaine, as he had promised his father he would, and this only acerbated the rivalry between the two brothers.

Third Crusade

Richard's first priority, indeed, perhaps his only one, was to make good on his promise made in 1187 to 'take the cross' and help capture Jerusalem from the Muslims. The king emptied his kingdom's coffers for his mission, even striking up a deal with William the Lion - giving the Scottish king full feudal autonomy in return for cash. For a monarch who spent most of his reign outside of England, did not speak English, and recklessly spent the kingdom's wealth on foreign wars, Richard has enjoyed a remarkably favourable position in the English popular imagination ever since.

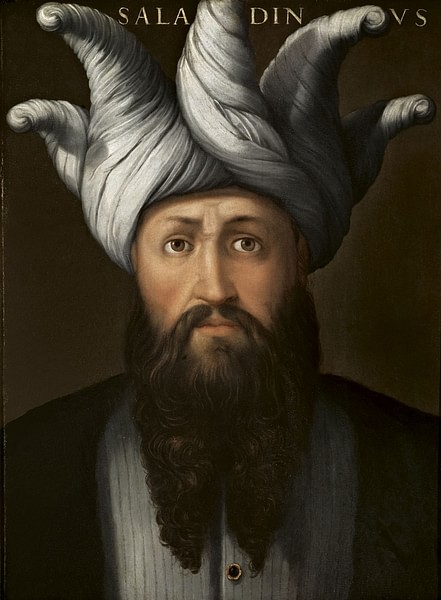

The Third Crusade (1189-1192) was called by Pope Gregory VIII following the capture of Jerusalem in 1187 by Saladin, the Sultan of Egypt and Syria (r. 1174-1193). No fewer than three monarchs took up the call: Frederick I Barbarossa (King of Germany and Holy Roman Emperor, r. 1152-1190), Philip II of France and Richard himself. With these being the three most powerful men in western Europe, the campaign promised to be a more favourable one than the Second Crusade of 1147-49. Unfortunately for Christendom, though, the Crusaders only managed to get within sight of Jerusalem and no attempt was made to attack the holy city. Indeed, the whole project was beset with problems, none bigger than Barbarossa drowning in a river before they even got to the Holy Land. The Holy Roman Emperor's death resulted in most of his army trudging back home in grief which left only the English and French knights, who were not particularly fond allies at the best of times.

Still, despite the bad start, there were some military highlights to write home about. Richard, who took the sea route to the Middle East, first captured Messina on Sicily in 1190 and then Cyprus in May 1191. In the latter campaign the island's self-proclaimed ruler Isaac Komnenos (r. 1184-1191), who had broken away from the Byzantine Empire, was captured and the Crusaders would then govern until the Venetians took over in 1571. However, these detours were not really helping the overall aim of recapturing Jerusalem, even if Cyprus proved to be a useful supply base.

The Crusaders did eventually arrive in the Holy Land and managed to bring a successful conclusion to the siege of Acre (aka Acra) on the coast of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, on 12 July 1191. Begun by the French nobleman Guy of Lusignan, who attacked from the sea, the protracted siege finally worked when sappers, offered cash incentives by Richard, undermined the fortification walls of the city on the land side. The 'Lionheart', as Richard was now known thanks to his courage and audacity in warfare, had achieved in five weeks what Guy had failed to do in 20. According to legend, the king was ill at the time, struck down by scurvy, although he had retainers carry him on a stretcher so that he could fire at the enemy battlements with his crossbow. Richard then rather blemished his 'good king' reputation when he ordered 2,500-3,000 prisoners to be executed. Guy of Lusignan, meanwhile, was made the new king of Cyprus which had been sold by Richard to the Knights Templar.

There was also a famous victory for the English king over Saladin's army at Arsuf, in September 1191, but the advantage could not be pursued. Richard marched to within sight of Jerusalem but he knew that even if he could storm the city, his reduced army would most likely not be able to hold it against an inevitable counterattack. In any case, domestic affairs in France and England necessitated both kings to return home and the whole Crusade project was effectively abandoned. Richard salvaged something for all the effort and negotiated a peace deal with Saladin at Jaffa. A small strip of land around Acre and the future safe treatment of Christian pilgrims to the Holy Land was also bargained for. It was not quite what was hoped for at the outset but there could always be a Fourth Crusade at some time in the future. Indeed, Richard noted that in any future campaign against the Arabs it could be advantageous to attack from Egypt, the weak underbelly of the Arab empire. It was precisely this plan which the Fourth Crusaders (1202-1204) adopted even if they again were distracted, this time by the jewel of the Byzantine Empire: Constantinople.

There were also some take-home technology innovations for the English king. The Byzantines had long used a fearsome weapon known as Greek Fire - a highly flammable liquid shot out of tubes under pressure - which, although a state secret for centuries, was eventually stolen by the Arabs. Richard must have acquired the formula from Arab alchemists he came into contact with on the Crusade for he used it to good effect back in England and on his later campaigns in France.

Before King Richard could return home, though, there would be one final sting of the ill-fated Crusade, for on the return journey in 1192 Richard was shipwrecked, arrested by Leopold of Austria (r. 1075-1095) - whom Richard had gravely insulted during the Crusade - and taken to Vienna. Passed on to Henry VI, the new Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1191-1197), the English King was held for ransom. Richard would only be released in 1194, and one can imagine the frustration for the swashbuckling king almost two years of captivity. The ransom was a massive 150,000 marks (which equates to several million dollars today) so that it was largely through new taxes in England and Normandy that the money was raised. Indeed, the sum was so high that even taxation could not raise enough, and Richard was forced to provide a number of noblemen hostages to make up for the shortfall.

Domestic Policies

While the king was fighting abroad, English politics was left in the capable hands of Hubert Walter, who was Bishop of Salisbury in 1189 and was made Archbishop of Canterbury in 1193. Walter proved himself an able statesman and events would unravel which required exactly that at the helm of the ship of state. While captive in the Holy Roman Empire, Richard's younger brother John, conspiring with Philip II of France, made an unsuccessful attempt to seize the throne, but Walter managed to contain the usurper thanks to the help of another able if somewhat insensitive minister: he who looked after the realm's purse strings in Richard's absence, the chancellor, William Longchamp. The war was principally one of sieges and control of strategically important castles such as at Nottingham and Windsor Castle but in the end, the crown prevailed. Richard forgave his brother his excessive ambition and even nominated him as his successor. Hubert Walter was also responsible for raising the hefty ransom which had gained his king's release. In 1193 Walter was made Chief Justiciar and given overall responsibility for government, a position he held until 1199.

One area the king was wary of was tournaments, those events where knights attacked each other in mock cavalry battles. Richard only permitted their organisation under license - allowing five places to host them - and made knights pay an entrance fee. The latter measure and the imposition of heavy fines for anyone daring to hold an unofficial event were a useful means to fill the state's coffers which were so often emptied by the king's expensive military escapades. Still, Richard also appreciated that tournaments could be a useful training ground for his knights and, soon to be up against the French, whose knights were famed for their horsemanship, he would need as skilled an army as he could muster.

Given Richard's need to fund his armies throughout his reign it is perhaps not surprising that he was nowhere near the big spender on English castles that his father had been. There was a major investment in revamping and extending the Tower of London in 1189-90 as indicated in the Pipe Rolls expenditure records but, otherwise, castle-building came to halt as the decade of the 1190s wore on. Yet another fund-raising strategy of the perennially cash-strapped king was to open up royal forests to local lords for hunting, with an appropriate fee, of course. Clearly, Richard needed all the money he could get his hands on for the conflicts yet to come.

Campaigns in France & Death

After a brief stint back in England and a second coronation in April 1194 at Winchester, Richard then spent much of his time on campaign in France where he defended the Angevin lands against his former Crusader ally, Philip II of France. The pair had fallen out when Richard did not marry Philip's sister Alice, despite the pair being engaged for 20 years. Richard instead had married Berengaria of Navarre (c. 1164-1230) on 12 May 1191, as arranged by his mother. Berengaria would be the only reigning English queen never to set foot in her own realm.

The English king assembled an army to attack Philip by requiring his barons to merely supply the king with only seven knights each instead of the usual vassal fighting force. As an alternative, Richard demanded cash with which he could purchase his own mercenaries. It was an arrangement the barons were only too happy to agree to as it meant they could remain, and defend if necessary, their own castles and lands rather than abandon them to opportunists while far away in France.

Richard might have neglected English fortifications but he invested big in Normandy, notably constructing the Chateau Gaillard by the River Seine from 1197 to better defend his territorial claims there. Then disaster struck. Richard was mortally wounded in Aquitaine during his siege of the castle of Chalus in 1199. The king, hit in the neck by a crossbow bolt, died on 6 April after the wound had become gangrenous. Richard was buried alongside his parents at Fontevraud Abbey near Chinon while his effigy at Rouen contains his heart.

Legacy

As he had no heir Richard I was succeeded by his brother John who would reign until 1216. King John of England (aka John Lackland) managed to make himself one of the most unpopular kings in English history, and his oppression and military failures brought about a major uprising of barons who obliged the king to sign the Magna Carta in 1215, upon which a constitution was based with the power of the monarch curbed and with the rights of the barons protected.

Richard, meanwhile, gained legendary status as one of the great medieval knights and kings thanks to his daring deeds and the love and respect of his soldiers. After his death the myths only grew bigger, starting with the Anglo-Norman novel Romance of Richard Cœur de Lion published around 1250. Already having proven himself as courageous, a determined foe of the Saracens and a composer of poetry to boot, Richard was the very model of the chivalrous knight and so his legend grew along those lines. Medieval artworks depicted the king improbably jousting Saladin, he was attributed fine speeches about saving his men or he would not be worthy of his crown, and stories sprang up of him being such a determined foe of the Arabs that he cooked and ate those he captured. Even today, the presence of a dramatic statue of the king outside the Houses of Parliament in London is an indicator of the special place Richard has gained and continues to hold in the hearts of Englanders.

Finally, Richard has left a lasting legacy in medieval heraldry. The king's choice of three golden lions (although they may originally have been leopards) on a red background on his shield were an extension of his family's traditional two lions. The three lions, perhaps originally rearing figures ('rampant' in heraldic terms) but subsequently established as strolling forward with their heads turned at the onlooker ('passant guardant') have become not only a part of the English royal coat of arms ever since but also appear today in many other badges, especially sporting ones such as the England national football and cricket teams.