In medieval Europe, a code of ethics known as chivalry developed which included rules and expectations that the nobility would, at all times, behave in a certain manner. Chivalry was, in addition, a religious, moral and social code which helped distinguish the higher classes from those below them and which provided a means by which knights could earn themselves a favourable reputation so that they might progress in their careers and personal relations. Evolving from the late 11th century CE onwards, essential chivalric qualities to be displayed included courage, military prowess, honour, loyalty, justice, good manners, and generosity - especially to those less fortunate than oneself. By the 14th century CE the notion of chivalry had become more romantic and idealised, largely thanks to a plethora of literature on the subject and so the code persisted right through the medieval period with occasional revivals thereafter.

Function & Promotion

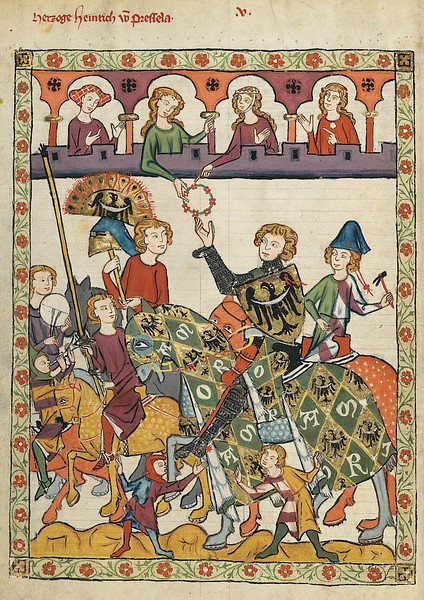

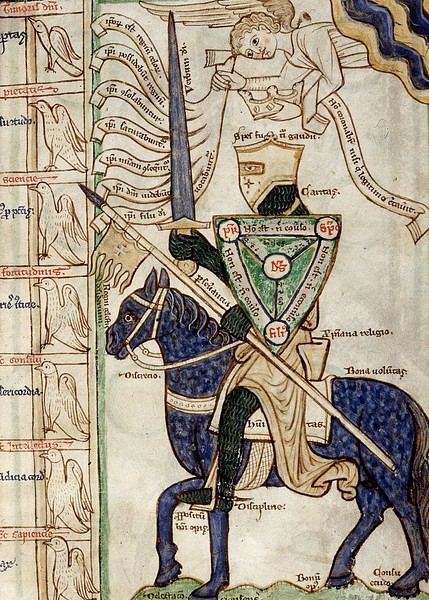

Chivalry, derived from the French cheval (horse) and chevalier (knight), was originally a purely martial code for elite cavalry units and only later did it acquire its more romantic connotations of good manners and etiquette. The clergy keenly promoted chivalry with the code requiring knights to swear an oath to defend the church and defenceless people. This relationship between religion and warfare only heightened with the Arab conquest of the Holy Lands and the resulting Crusades to reclaim them for Christendom from the end of the 11th century CE. The state also saw the benefits of promoting a code by which young men were encouraged to train and fight for their monarch. The discipline of the chivalric code must also have helped when armies were in the field (but not always), as did its inspirational emphasis on display; knights preened about the battlefield like peacocks with jewelled swords, inlaid armour, plumed helmets, liveried horses and colourful banners of arms. The magnificent sight of a troop of heavily armoured knights galloping on to the battlefield won many a medieval conflict before it had even started.

Romantic novels, poems and songs (chansons de geste) were written which promoted further still the ideal of chivalry with their rousing tales of damsels in distress, courtly love (the unrequited and unattainable love of a married aristocratic lady) and heroic, wandering champions (knight errants) fighting foreigners and monsters - which were essentially the same. The spread of the literature on the legendary figure of King Arthur and his knights of the Round Table from the 12th century CE was especially influential on instilling ideals of honour and purity into the minds of medieval noblemen: in the Arthurian tales only the good and true would find the Holy Grail. Other figures from history which became examples to follow and who appeared as characters in the chivalric literature included Hector of Troy, Alexander the Great and Charlemagne. There even developed a literature of helpful chivalry guides for knights such as the French poem The Order of Chivalry (c. 1225 CE) which considered the correct initiation process for knighthood, the Book of the Order of Chivalry by the Aragonian Ramon Llull (1265 CE) and the Book of Chivalry by the French knight Geoffroi de Charny (published around 1350 CE). Perhaps most important of all sources on chivalry for later historians, at least, was the Chronicles by the historian Jean Froissart, written in the latter half of the 14th century CE.

Chivalry had another purpose besides making people well-mannered: to clearly separate the nobles from the common people. After the Norman Conquest of 1066 CE in England, for example, social divisions had become a little blurred and so chivalry became a means by which the nobility and landed aristocrats could persuade themselves they were superior and had a monopoly on honour and decorous behaviour. Knighthood thus became a sort of private members club where wealth, family lineage and the performance of certain initiation ceremonies allowed a person to enter the clique and then openly display their perceived superiority to the masses.

To keep up the standards of chivalry there developed over time certain restrictions on just who could become a knight. In 1140 CE Roger II, King of Sicily, for example, forbade any person who might disturb the public peace from being made a knight. In 1152 CE a decree in the Kingdom of Germany prohibited any peasant from ever being made a knight. Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I made a similar law in 1186 CE, banning across the Empire the sons of peasants or priests from ever becoming a knight. Gone were the early days of chivalry when anyone who displayed great courage in battle stood a chance of being made a knight by a grateful lord or monarch. By the 13th century CE the idea had taken hold across Europe that only a descendant of a knight could become one. There were exceptions, especially in France and Germany during the 14th century CE when the sale of knighthoods became a handy way for kings to increase their state coffers but generally, the now prevailing view was that honour and virtue could only be inherited, not acquired.

Punishment & Demotion

There was a downside to parading around the countryside declaring to all and sundry how honourable one was, because the chivalric code also had its punishments for those who failed to meet its standards. A knight faced having his status removed and good name sullied forever if he were guilty of serious misdemeanours like fleeing a battle, committing heresy or treason. There was even a rule against a knight spending money too frivolously. If the unthinkable did happen to a knight then his spurs were removed, his armour smashed and his coat of arms removed or thereafter given some shameful symbol or only represented upside down.

Chivalric Orders

As knighthood and chivalry became more and more important as social status symbols, and at the same time loyalty to the church was replaced by that towards the crown, so specific orders arose - often initiated by monarchs - to create a hierarchy within the world of knights. The English king Edward III (r. 1327-1377 CE) was particularly noted for his support of tournaments and the cult of chivalry. At one tournament the king organised at Windsor Castle in 1344 CE, 200 knights were invited to join a chivalric brotherhood and then in 1348 CE he created the even more exclusive Order of the Garter for 24 chosen knights plus the king and his son, the Black Prince, who all proudly wore a dark blue garter. The order with its accompanying honours still exists today. Already, in Hungary in 1325 CE King Charles had founded the Order of Saint George and in 1332 CE King Alfonso XI of Castile and Leon had established the Order of the Sash. In France in 1351 CE, King John the Good (r. 1350-1364 CE) founded the chivalric Order of the Star whose specific aims were to promote chivalry and honour. The Order of the Star also imposed a 'never retreat in battle' clause on its membership which may have been highly chivalrous but in the practicalities of warfare often proved disastrous - half the order was killed in one battle in Brittany in 1353 CE.

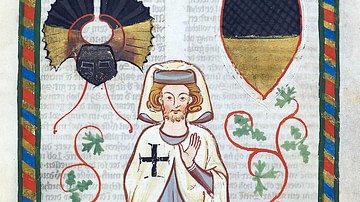

Initiation into special orders might involve the knight-elect taking a bath, donning symbolic robes and being blessed in a chapel while knights of the order looked on. The new knight might also be required to keep a vigil in the chapel overnight and, in the morning and after another religious service and a hearty breakfast, the initiate was ceremoniously dressed by two knights. It was then he was given his spurs, armour, helmet and freshly-blessed sword. The last stage of the elaborate ceremony involved the most senior knight of the order giving the new recruit a belt and then striking him on the shoulders with his hand or sword.

The Medieval Tournament

One of the best places, besides the actual battlefield, for a knight to show off all his qualities of chivalry was the medieval tournament. Here, at the mêlée (a mock cavalry battle) or one-on-one jousts, a good knight was expected to possess and display the following qualities:

• martial prowess (prouesse)

• courtesy (courtoisie)

• good breeding (franchise)

• noble manners (debonnaireté)

• generosity (largesse)

Given the importance of chivalry, those who had, amongst other misdemeanours, slandered a woman, been found guilty of murder or who had been excommunicated were banned from competition. Those who did win at tournaments could gain both honour and riches. The fact that fellow nobles were watching and perhaps too a lady of court whom the knight had taken a fancy to or whose favour he was sporting on his lance were additional spurs for competitors to achieve great deeds of valour and chivalry

Warfare & Chivalry

While the life of a man of arms was itself regarded as a noble pursuit it is important, perhaps, to note that although chivalry came to the fore in peacetime pursuits, it was largely absent during actual warfare and the slaughter of enemies, murder of prisoners, rape and pillaging all went on as tragically as it had done for millennia before the concept of chivalry was formed. Still, at least in theory, knights were supposed to pursue warfare for honour, the defence of the Christian faith or their monarch rather than mere financial gain.

A certain ethical code of conduct did develop in warfare and especially the humane and gracious treatment of prisoners but, of course, such ideals were not followed by all knights in all conflicts. Even such epitomes of chivalrous behaviour as Richard I of England was known to have slaughtered defenceless prisoners during the Third Crusade (1189-1192 CE). Certainly, by the acrimonious Wars of the Roses in England during the 15th century CE, a knight's good name and social standing was unlikely to guarantee him chivalrous treatment if he were on the losing side of a battle and a noble surname might actually be a death sentence in itself, such were the family rivalries of the period. Still, some general points of chivalry were the warning of a siege by heralds so that the city's residents could either surrender or its non-combatants could flee. Sometimes, citizens were even permitted to leave mid-siege during a general truce. If and when a city did fall there was also the expectation that churches and the clergy would not be harmed.

As armies contained many other elements besides knights, it was often impossible for the noblemen to ensure rules of chivalry were followed by all, especially in the chaos of victory. There was certainly, too, a difference in chivalry depending on who the enemy was. Infidels during the Crusades, for example, were not considered worthy of genteel treatment while civil wars against fellow knights might foster a greater degree of chivalry from the combatants. Finally, the chivalric code was sometimes at odds with the one essential feature of any successful army: discipline. Knights had had the idea of personal valour and glory drilled into them to such an extent that their desire to display courage could lead to foolish risk-taking and a disregard for the needs of the army as a whole to act as a disciplined fighting unit. One such infamous case involved the Templar Knights at the siege of Ascalon (in modern Israel) in 1153 CE when 40 knights attempted to storm the battlements themselves and even prevented rival units on their own side from joining in the attack. In the end, the Templars were defeated and their heads hung from the city's walls - sometimes discretion really was the better part of valour, even for chivalrous knights.