Marie de France (wrote c. 1160-1215 CE) was a multilingual poet and translator, the first female poet of France, and a highly influential literary voice of 12th-century CE Europe. She is credited with establishing the literary genre of chivalric literature (though this is contested), contributing to the development of the Arthurian Legend, and developing the Breton lais (a short poem) as an art form. Marie's published works include:

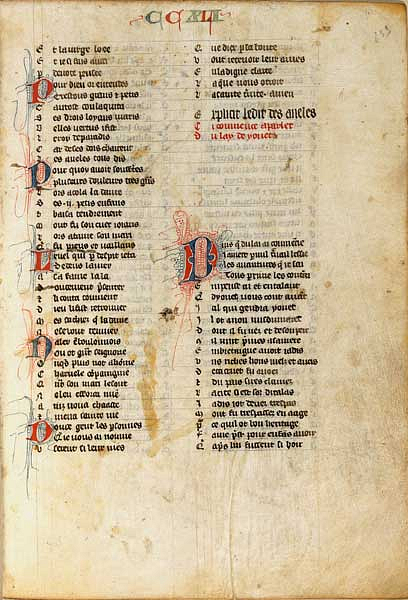

- Lais (including the Arthurian works Chevrefueil and Lanval)

- Aesop's Fables (a translation from Middle English to French) and other fables

- St. Patrick's Purgatory (also known as The Legend of the Purgatory of St. Patrick)

She was trilingual, writing in the Francien (Parisian) dialect with a command of Latin and Middle English. Her lais were developed from the earlier Breton lais poetic form and so she must have also known Celtic Breton and been acquainted with Brittany. Her works influenced later poets, notably Geoffrey Chaucer, and her imagery in St. Patrick's Purgatory would be used by later writers in depictions of the Christian afterlife.

Marie's works were popular in aristocratic circles but frequently featured lower-class characters as more worthy and noble than their supposed social superiors and always cast women as strong central characters. Her vision of female equality has led to her designation as a proto-feminist in the modern day, and her works remain as popular as they were in her lifetime.

Identity

Her actual name is unknown – `Marie de France' is a pen name given her only in the 16th century CE. All that is known of her comes from her work in which she identifies herself as Marie from France. Based on details in her work including knowledge of place names and geography, and the sources she drew from, scholars have determined that Marie spent a significant amount of time in England at the court of Henry II (r. 1154-1189 CE) and his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine (l. c. 1122-1204 CE).

Scholars suggest Marie may have been Henry's half-sister who perhaps followed him from Normandy to England when he was crowned king in 1154 CE. The Lais of Marie de France are dedicated to “a noble king” who is most likely Henry II but precisely how Marie meant this dedication is unclear. Marie's poetry often features women imprisoned or otherwise poorly treated by men and this theme mirrors Henry's relationship with Eleanor.

Throughout their marriage, Henry was unfaithful to his wife numerous times and carried on an open affair with the noblewoman Rosamund Clifford. When Henry's sons rebelled in 1173-1174 CE with Eleanor's support, the king had her imprisoned for the next 16 years. This same sort of relationship, often with similar details, appears in a number of Marie's works. Further, Henry does not seem to have been as fond of poetry and poets as his wife was and so an interpretation of Marie's dedication as sarcastic is probable.

In modern-day scholarship, Marie is almost always credited with establishing the genre of chivalric literature, but this seems unlikely as her works clearly draw on a pre-existing tradition of courtly love literature whose central motifs she inverts. In courtly love poetry, the knight is seen rescuing the damsel in distress; in Marie's works, the knight is often the one who has imprisoned her in the first place or, sometimes, the one in need of rescue.

Courtly Love & Arthurian Romance

Courtly love was possibly a social game of the medieval French courts or possibly an allegorical representation of the heretical sect of the Cathars – no one knows – but the concept of an exalted, passionate love between a married lady and a single knight was central to the poetry of the troubadours of southern France in the 12th century CE. The greatest of these poets was Chretien de Troyes (l. c. 1130-1190 CE) who established some of the most recognizable aspects of the Arthurian Legend such as Lancelot's affair with Guinevere, the Grail Quest, and the name of Arthur's court as Camelot. Authors of medieval literature wrote under the patronage of a member of the nobility who paid them for their work, and Chretien's patroness was Marie de Champagne (l. 1145-1198 CE), daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine who was likely patroness to Marie de France.

Chretien's works illustrated the world of courtly love by establishing models of chivalric behavior in which a lady commanded a knight's complete devotion and the knight would endure any hardship or humiliation for the honor of serving her. The best example of this is Chretien's Lancelot or the Knight of the Cart, in which Guinevere is abducted by the villain Meleagant and Lancelot pursues them. When his horse dies, Lancelot must continue on foot but soon meets a dwarf driving a cart who says he will help if the knight will consent to ride in the cart. Carts were associated with criminals and the lower class and so Lancelot hesitates, only for a moment, but then mounts the cart.

Throughout the rest of the work, Lancelot is repeatedly humiliated for riding in the cart but eventually reaches Guinevere in her tower and attempts to rescue her. She rebukes him, however, for his earlier hesitation; he placed his own honor and how others would regard him above devotion to her. Lancelot must then win her back by proving himself, even going so far as to lose to less-worthy competitors in a tournament when Guinevere asks him to. In the end, however, Guinevere is rescued by her knight. This was the vision of courtly love, and it was this world which Marie de France inverted.

In Marie's poem Yonec, to cite just one example, a beautiful young maiden is taken by the old lord of the village of Caerwent and brought to his castle. She is so pretty, her lord fears she will be unfaithful to him and locks her in a high tower. As the years go by, the maiden begins to wither from lack of love and prays to God to send her a champion who will save her, the same kind of hero she has read about in romantic literature.

After her prayers one day, she sees a hawk approach her window who turns into a handsome knight, Muldumarec, and becomes her lover. Whenever the old lord is away from the manor, Muldaumarec visits the maiden. The lord has his sister watching over the maiden but the sister has never noticed anything suspicious until the maiden begins to glow with beauty because of her newfound love. Watching more closely now, the sister sees Muldaumarec arrive as a hawk and hurries to tell the lord. The lord then sets iron spikes in the window, and the next time the hawk alights, he is mortally wounded. He manages to fly away, and the maiden leaps from her tower and follows him, finally finding him in a silver city. Dying, he tells her she is pregnant but gives her a magical ring which will cause her lord to forget about their affair. He also gives her a sword which he tells her to give their son, who will one day avenge his father's death.

The maiden returns to her imprisonment with the lord and gives birth to a son, whom she names Yonec. When the boy has grown, she is traveling with him and her lord, and they come to the place where the silver city used to be, now an abbey. There is the grand tomb of the prince Muldumarec, however, and the maiden falls down in grief at the memory of her lover. She tells her son the story of his father and gives him the sword, then dies at the foot of the tomb. Yonec kills the lord, has his mother buried next to Muldumarec, and becomes the new lord of Caerwent.

This story of an imprisoned woman hoping for rescue obviously departs from the motifs of Chretien's tale on a number of points, but most markedly, the woman is forced to save herself. The maiden prays for a hero and takes that hero as her lover but Muldumarec cannot rescue her. She escapes from her tower and then, finding herself in the outside world with no protection or livelihood, submits herself again to her prison and finally is instrumental in avenging her lover. Throughout Marie's works, she frequently depicts marriage as a prison and adulterous love affairs as freedom, challenging the views and authority of the medieval Church and the aristocracy.

Marie's two Arthurian works continue this theme as Chevrefueil (“honeysuckle”, a central motif of the poem) celebrates the adulterous love of Tristan and Isolde at a pageant thrown by Isolde's husband (and Tristan's uncle) Mark. Lanval goes further, however, in depicting the married queen Guinevere as unhappily bound to a man she does not love while the fairy princess – who chooses Lanval as her lover – is bright and joyful as a single woman. Lanval further inverts the courtly love paradigm in that, in this poem, it is the lady who saves the knight.

Lanval leaves King Arthur's court after feeling insulted and enters the realm of the fairy princess. The two fall in love, and the princess swears him to secrecy regarding their affair. When Lanval returns to court, Guinevere propositions him and he refuses. She accuses him of being a coward that he must be a homosexual to refuse her, and he feels he has no choice but to tell her he is in love with the fairy princess, thus breaking his vow. Guinevere, insulted, tells Arthur that Lanval propositioned her, and Lanval is placed on trial.

It appears he will be convicted but the fairy princess arrives just in time, riding on a modest palfrey, and rescues him, pulling him up onto the back of her horse. The final image of the poem – of the knight riding on a palfrey (instead of a warhorse) clinging to the waist of his lady – is a striking inversion of the motif of the knight rescuing the damsel in distress and carrying her off into the sunset.

It is unclear how closely the works of authors such as Chretien mirrored the upper-class society's ideal of romantic relationships but Marie's consistently depict such relationships more in keeping with what is known of a woman's position in medieval society. Marie depicts a married couple's relationship as one-sided, with the male having the upper hand and the woman having to rely on her own strength and abilities to escape from an intolerable situation. The unhappy marriage was largely the situation of the women who made up her reading audience, and their enthusiasm for her work made her popular enough to be translated into other languages and even merit criticism from other authors.

Works & Criticism

As with every aspect of Marie's life and work, any attempt to date her poems and fables is speculative. Some scholars believe she began her career as a translator and so her Aesop's Fables and other fables came first, while others claim the poems were earlier and the fables followed. It is likely that the fables came first because, in her prologue to her Lais, Marie comments on those who have criticized her work unjustly and so, obviously, she must have published something previously.

Although scholars suspect that there was probably significant criticism of Marie's work, only one critics' comments are extant, those of the monk Denis Pyramus (c. 1180 CE, also given as Piramus) of Bury St. Edmunds Abbey, who condemns one “Dame Marie” as writing works “that are not at all true” but that “please the ladies; they listen to them joyfully and willingly, for they are just what they desire” (Lindahl et al., 255). It is no surprise that a monk should criticize Marie's work as it went directly against the teachings of the Church that women were worth less than men. Marie responds to this criticism, possibly to Pyramus specifically, in the prologue to her poem Guigemar:

Hear, my lords, the words of Marie who, when she has the opportunity, does not squander her talents. Those who gain a good reputation should be commended but when there exists in a country a man or woman of great renown, people who are envious of their abilities frequently speak insultingly of them in order to damage their reputation. Thus they start acting like a vicious, cowardly, treacherous dog which will bite others out of malice. But just because spiteful tittle-tattlers attempt to find fault with me, I do not intend to give up. (Burgess & Busby, 43)

The poem which follows this passage, the Guigemar, is one of the few of Marie's works with a happy ending in which a knight saves his lady but, in keeping with her usual vision, the lady must first rescue herself. The poem features the knight Guigemar who is wounded early on and can only be healed by a woman who loves him as much as he loves her. The knight stumbles into a boat which takes him against his will to a far-off land where he is healed by a maiden and her lady who are both imprisoned in a tower. Guigemar and the lady fall in love but are discovered by the lady's husband, who banishes the knight and again imprisons his wife. Before they part, the lady gives Guigemar a knot only she can untie and he gives her a belt only he can undo.

The lady cannot endure her imprisonment any longer and escapes, taking the same mysterious boat which brought Guigemar to her, and arrives in his lands of Brittany only to be abducted by another lord and imprisoned. The belt Guigemar gave her prevents the lord from raping her, and Guigemar knows the lady is truly his when she unties the knot she gave him earlier; he then rescues her after a bloody battle in which the evil lord is killed.

These kinds of themes are also explored in Marie's 102 fables, many of which are translations of Aesop's work with some of Marie's own composition (or, at least, embellishment). Following Aesop's lead, many of Marie's fables feature animals, and the dynamic of the relationship between the sexes is just as fraught with peril in the natural world as in that of knights, ladies, and courts. Females are frequently tricked, conned out of their comfortable homes, raped or threatened with rape, and must either find some way to free themselves or succumb.

In Marie's fable The Mouse and the Frog, for example, a happy mouse is tricked into abandoning her home to follow the frog across a swampy field. The mouse only escapes after making noise which attracts a kestrel who swoops down and takes the frog, leaving the mouse to return to her home. In The Wolf and the Lamb, an angry, overbearing wolf finds fault with the way a lamb is drinking downstream from him and begins a quarrel, which ends with him killing the little lamb. In this fable, the lamb is male but is forced into the position of many female characters in Marie's work in having to submit to a powerful patriarchal figure. When the lamb refuses to submit, the wolf hills him, and Marie concludes the fable by noting how the wolf is like the judges and nobles who destroy the lives of the simple folk through their entitlement and arrogance.

Conclusion

Marie's compassion for the lower classes is also evident in St. Patrick's Purgatory which is her own version of an ecclesiastical piece written in c. 1180 CE by the monk Henry of Saltry. Henry's piece emphasized the Church's teaching on sin and punishment; Marie's focuses on the hero Owen's journey through hell and his redemption through his own merits, not those of the Church. The souls Owen encounters in his journey are depicted sympathetically, not always deserving of the fate the Church has allotted them. Scholar Pack Carnes comments:

Indeed, all of Marie's surviving works are infused with a sense of compassion rare for her time, a compassion that extends even beyond her sympathy for the plight of women. (Lindahl et al., 257)

Carnes further notes how the peasants who appear in Marie's works are consistently intelligent, noble, and worthy of respect, unlike their depictions by other authors of the time. Marie's women, knights, nobility, and peasants would influence later writers such as Christine de Pizan, Geoffrey Chaucer, Dante Alighieri, and Thomas Malory. In the epilogue of her Fables, she writes:

At the conclusion of this work, which I have written and narrated in French, I shall name myself for posterity: Marie is my name and I am from France. It may be that many writers will claim my work as their own but I want no one else to attribute it to himself. He who lets himself fall into oblivion does a poor job. (Martin, 253)

Marie, as it turns out, had nothing to fear as her name has always remained attached to the work which has been admired since its publication. Marie's remarkable imaginative power and artistic skill ensured she would be remembered as her poems and fables were so popular in her time that they were copied and recopied; more of her work survives intact today than most writers of her time. In the present day, 800 years after she lived, she is still regarded as one of the greatest poets of the Middle Ages.