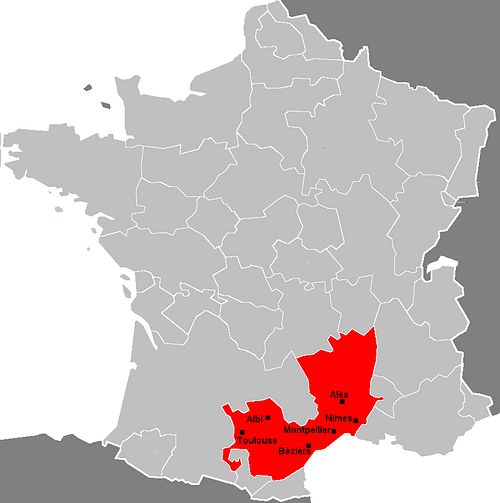

The Cathars (also known as Cathari from the Greek Katharoi for “pure ones”) were a dualist medieval religious sect of Southern France which flourished in the 12th century and challenged the authority of the Catholic Church. They were also known as Albigensians for the town of Albi, which was a strong Cathar center of belief.

Cathar priests lived simply, had no possessions, imposed no taxes or penalties, and regarded men and women as equals; aspects of the faith which appealed to many at the time disillusioned with the Church. Cathar beliefs ultimately derived from the Persian religion of Manichaeism but directly from another earlier religious sect from Bulgaria known as the Bogomils who blended Manichaeism with Christianity.

Cathars believed that Satan had tricked a number of angels into falling from heaven and then encased them in bodies. The purpose of life was to renounce the pleasures and enticements of the world and, through repeated incarnations, make one's way back to heaven. To this end, the Cathars observed a strict hierarchy:

- Perfecti – those who had renounced the world, the priests and bishops

- Credentes – believers who still interacted with the world but worked toward renunciation

- Sympathizers – non-believers who aided and supported Cathar communities

Cathars rejected the teachings of the Catholic Church as immoral and most of the books of the Bible as inspired by Satan. They rejected the Church for what they saw as hypocrisy of the clergy and the Church's acquisition of land and wealth. The Church responded by condemning the Cathars as heretical and they were massacred in the Albigensian Crusade (1209-1229) which also devastated the towns, cities, and culture of southern France.

Origins & Beliefs

Almost everything known about the Cathars comes from confessions of “heretics” taken by Catholic clergy during the inquisition which followed the Albigensian Crusade. The belief structure can easily be traced back to Manichaeism which traveled via the Silk Road from the Byzantine Empire and the Middle East to Europe where it became entwined, under certain circumstances, with Christian belief and symbolism.

The orthodox view of the Catholic Church was that there was one God with three aspects – Father, Son, and Holy Ghost – but this orthodoxy was not part of the vision of early Christianity and was not generally accepted until after the Council of Nicaea in 325 (convened by Constantine, the first Christian emperor of Rome) ruled in favor of it. Even then, the Nicaean interpretation of Christianity vied with others for centuries. The so-called heretical movements of the Middle Ages such as the Bogomils, the Cathars, and the Waldensians were simply the latest challenges to the Church, but they were significant because they were the first to set themselves up as a legitimate alternative to Catholicism in any form.

Cathar beliefs included:

- Recognition of the feminine principle in the divine – God was both male and female. The female aspect of God was Sophia, “wisdom”). This belief encouraged equality of the sexes in Cathar communities.

- Metempsychosis (Reincarnation) – a soul would be continually reborn until it renounced the world completely and escaped incarnation.

- Cosmic Duality – the existence of two powerful deities in the universe, one good and one evil, who were in a constant state of war. The purpose of life was to serve the good by serving others and escape from the cycle of rebirth and death to return home to God.

- Vegetarianism - though eating fish was allowed to credentes and sympathizers.

- Celibacy for perfecti – celibacy was also encouraged generally since it was thought that every person born was just another soul trapped by the devil in a body. Marriage overall was discouraged.

- The dignity of manual labor – the Cathars all worked, priests as well as laypeople, many as weavers.

- Suicide (known as the ritual of endura) as a rational and dignified response under certain conditions.

Earlier heresies such as Arianism, while still condemned, at least adhered to the same essential dogma of the Church; the Cathars rejected and repudiated every aspect of the Church, including most of the books of the Bible. Scholar Malcolm Barber notes:

They believed that the devil was the author of the Old Testament except these books: Job, the Psalms, the books of Solomon [Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon], The Book of Jesus son of Sirach [better known as the Book of Ecclesiasticus], of Isaiah, Ezekiel, David, and of the twelve prophets. (93)

The Book of Two Principles

The only books of the New Testament they accepted were the gospels, completely rejecting the epistles of Paul and the others, with a special emphasis on the Gospel According to John. Their central religious text was The Book of Two Principles, passages of which would be read by one of the perfecti to a congregation and interpreted for them by another member of the group. The Book of Two Principles related, among other aspects of the faith, the dualist nature of life and how humans, once divine spirits of light, came to be bound in corruptible mortal flesh.

The story goes that the devil came to the gates of heaven and requested entry but was denied. He waited outside the gate for a thousand years, watching for a chance to slip in, and one day he saw his opportunity and took it. Once inside, he gathered an audience of divine spirits around him and told them they were losing out by continuing to love and serve God who never gave them anything. They were little more than slaves, he said, since God owned everything they thought they had. If they would follow him, however, and leave heaven, he could provide them with all kinds of pleasure such as lovely vineyards and rich fields, beautiful women and handsome men, wonderful riches, and the best wine.

Many souls were seduced and for nine days and nine nights they fell through the hole in heaven the devil had created. God allowed this for those who wished to leave but other souls were falling through the hole and so God sealed it. After the souls had fallen, they found themselves in the devil's realm without any of the good things he had promised and, remembering the joys of heaven, they repented and asked the devil if they could return. The devil replied that they could not because he had fashioned for them bodies which would bind them to earth and cause them to forget all about heaven.

The devil made the bodies easily enough but could not manage to attach the souls to them so they would think, feel, and move; vexed by this, he asked God for help. God understood that the souls who had fallen would have to work their way back to his grace and that they could do so through struggling with these bodies so he made a deal with the devil: the devil could do as he liked with the bodies, but the souls which animated them belonged to God. The devil consented, and humans were created.

Trapped in these bodies, the soul would live, die, and be reborn in another as long as that soul remained attached to the body and the pleasures which the devil had promised it back in heaven. Once the soul renounced the body and all its temptations, it would be freed to return to God and resume its former state. The whole purpose of human existence was this struggle against the devil (known as Rex Mundi, “the king of this world”) and the prison of the flesh.

Conflict with the Church

This view contrasted sharply with the Church's vision of a Garden of Eden in which woman, in the form of Eve, had caused humanity's fall by seducing Adam into eating of the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, and of humanity's later redemption from sin through the sacrifice of Jesus Christ, the son of a single, all-powerful, male god. Suicide was (and is still) considered a serious sin by the Church, marriage is encouraged, reincarnation rejected, as is the concept of duality. In Catharism, God and the devil are two eternal, uncreated, forces of equal power; in Christianity, the devil is a fallen angel created by God and ultimately subordinate to him.

In addition to these differences, there was the Cathar insistence that Jesus had never been born of a woman and been made flesh, never suffered, died, and was therefore never resurrected. All these events, as told in the gospel narratives, they interpreted as happening ideally as a sort of allegory for the state of the soul which is born into the world trapped in a body, must suffer and die, and will finally be free only after it has mastered the body and renounced the things of this world.

The Cathars, therefore, repudiated the symbol of the cross and a literal reading of any of the biblical books. They considered the cross a symbol of Rex Mundi and believed it should be destroyed when encountered as it was a representation of evil. The cross, they claimed, was nothing more than a symbol of worldly power, and all the sacraments of the church, including infant baptism and communion, were likewise rejected.

Cathars who were not celibate practiced birth control and abortion, believing that sex was a natural aspect of the human condition and could be engaged in for pleasure, not only for procreation. Women were valued as men's equals and female figures from the Bible were highlighted, especially Mary Magdalene and the Virgin Mary. Some scholars have suggested, in fact, that the growth of the Cult of the Virgin Mary in medieval Europe – which became an increasingly popular and influential movement – was encouraged by the Cathars' elevation of womanhood.

Growth & Organization

The Cathars lived in communities which varied in size from 60 to 600 individuals. They shared their possessions and took care of each other as a family. The faith gained a strong foothold in Italy and Southern France through its appeal to the peasantry. Scholar Martin Erbstosser notes how “it was the life of the perfecti rather than the teachings of the heretics which played the key part here” (92). The perfecti were thought to live such blameless lives, and were so eager to be of assistance to others, they inspired devoted followers.

The faith did not remain restricted to the peasantry for long but spread up the medieval hierarchy to artisans like weavers and potters, writers and poets, merchants and business owners, members of the Catholic clergy, and finally nobility. Eleanor of Aquitaine (l. c. 1122-1204 CE) and her daughter Marie de Champagne (l. 1145-1198 CE) were both associated with the Cathars as sympathizers.

The Cathars dressed simply in dark robes with hoods or hats, went about barefoot, and the men were unshaven with long beards. They appear in small numbers in records from the 1140's in France, but by 1167, there were enough communities in the region to require an assembly to set rules and boundaries. The Council of Saint-Felix of 1167 organized the Cathar communities into bishoprics, each with a presiding bishop who was responsible only to his own flock. There was no central authority like the Pope of Rome. The council was presided over by a Bogomil cleric named Nicetas (1160's) which firmly establishes Bogomilism as the direct source of Catharism.

To become a Cathar, one simply professed one's belief and received the consolamentum, a blessing and welcoming to the faith through the laying on of hands. To become one of the perfecti, one completely renounced the world and went through a period of withdrawal and purification before taking office. Men and women were perfecti. There were no official services or masses as with the Church but rather informal gatherings which seem to have been in adherent's homes.

In Southern France, where the church had never had a very strong hold, Cathars lived and worked among the wider community and convened their gatherings without concern. Elsewhere, they had to be more careful and hide their faith. This practice, according to some scholars, gave birth to the most popular literary genre of the Middle Ages: the poetry of courtly love.

Courtly Love & the Cathars

Courtly love poetry developed in Southern France at the same time as the Cathar heresy. The common theme of this body of medieval literature is the beautiful woman who commands worship and service by a courteous, brave, and noble knight. The famous literary motif of the damsel-in-distress who must be rescued comes from this genre, and its most famous author was the French poet Chretien de Troyes (l. c. 1130 – c. 1190) whose patroness was Marie de Champagne. Chretien is best known for creating some of the most famous elements of the Arthurian Legend such as Lancelot's affair with Arthur's queen Guinevere, the quest for the Grail, and is the first to call Arthur's court Camelot.

The poems often involve a quest or some struggle to find or rescue a lady who has been abducted or imprisoned. Women frequently play important roles in these stories and, in a reversal of earlier medieval literary motifs, are central characters who are served by men rather than minor figures and men's property. Most importantly, the poems celebrated romantic love, which, in this genre, was considered quite different, and far superior, to marriage because in marriage the couple had no choice (the match was arranged by the parents) while one chose to engage in extra-marital or pre-marital love affairs.

The scholar C. S. Lewis points out how, in the modern day, these themes seem commonplace and far from surprising but if one compares the poetry of 12th-century Provence with works like Bede's history or Beowulf, one realizes what a startling departure this was. Lewis and others cite Catharism as a probable inspiration for these works and claims they were allegories of the Cathar vision. The damsel-in-distress was the feminine principle of God, Sophia, who had been abducted by the Catholic Church, and the brave knight was the Cathar adherent who loved, served, and was sworn to rescue her. According to this theory, Catharism spread as widely and quickly as it did through the troubadours who traveled through France performing these works.

Albigensian Crusade

Whether the poetry was religious allegory helping spread the faith or whether the Cathars simply seemed to provide a better alternative to the medieval church, by the late 12th century, Catharism was winning more adherents than ever. Papal legates had been sent to Southern France to try to win the heretics back to orthodoxy, and councils had been called to discuss the problem; none of these efforts had made any headway.

In 1208, Pope Innocent III (served 1198-1216) sent the lawyer-monk Pierre de Castelnau to Southern France to enlist the aid of Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse (r. 1194-1222) in suppressing the heresy. Raymond was not only an ardent protector and supporter of the Cathars but also the bishop of the order in Toulouse. He refused to cooperate with the pope's legate and sent him away; Castelnau was later found murdered.

Pope Innocent then called for a crusade against Southern France, promising the nobles of the north they could keep all the rich lands and booty of their southern neighbors after the Cathars had been killed and their supporters crushed. The northern nobles complied and the Albigensian Crusade was launched in 1209.

Since the majority of Cathars were women, it was mainly women and children who were massacred in the crusade, but often whole towns went up in flames and all the citizenry killed. It is said that, at the siege-turned-massacre of the town of Beziers, when Arnaud-Amaury (the Cistercian monk commanding the Church's forces) was asked how to tell the difference between a heretic and a believer, he said, “Kill them all, the Lord knows who are His” (Bryson & Movsesian, 12). According to Church documents, 20,000 heretics were slaughtered in and around Beziers and the town burned to the ground.

After 1209, and the sack of Carcassonne, the earl Simon de Montfort (l. c. 1175-1218) led the crusade which continued the destruction of the region while enriching the northern barons who participated. By 1229, the “official” crusade was over but the Cathars were still persecuted and northern armies continued to sack villages and murder innocent people. Between May of 1243 and March of 1244, the Cathar stronghold of Montsegur held against siege but was finally taken and the last Cathar defense fell. In the massacre which followed, 200 perfecti were burned alive on a large pyre.

Conclusion

According to scholars Bryson and Movsesian, the Albigensian Crusade destroyed the tolerant culture of Southern France, replacing it with the far more rigid vision of the medieval Church but did nothing to stamp out Catharism itself. The Cathars who survived the purge of the early 13th century continued to live as they had before, only with greater care and secrecy.

The survival of these communities is known through Church records of inquisitions which continued on through the 14th century. As an organized religious sect, Catharism was extinguished in Southern France at Montsegur, but as a living faith, it continued. Later "heretical" movements all borrowed in some way from the Cathars who, in standing up to the authority of the medieval Church, prefigured the Protestant Reformation.