Religion in the Middle Ages, though dominated by the Catholic Church, was far more varied than only orthodox Christianity. In the Early Middle Ages (c. 476-1000), long-established pagan beliefs and practices entwined with those of the new religion so that many people who would have identified as Christian would not have been considered so by orthodox authority figures.

Practices such as fortune-telling, dowsing, making charms, talismans, or spells to ward off danger or bad luck, incantations spoken while sowing crops or weaving cloth, and many other daily observances were condemned by the medieval Church which tried to suppress them. At the same time, heretical sects throughout the Middle Ages offered people an alternative to the Church more in keeping with their folk beliefs.

Jewish scholars and merchants contributed to the religious make-up of medieval Europe as well as those who lived in rural areas who simply were not interested in embracing the new religion and, especially after the First Crusade, Christians and Muslims interacted to each other's mutual benefit. As the medieval period progressed, the Church exerted more control over people's thoughts and practices, controlling – or trying to – every aspect of an individual's life until the corruption of the institution, as well as its perceived failure to offer any meaningful response to the Black Death pandemic of 1347-1352, brought on its fracture through the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century.

Early Middle Ages & Pagan Christianity

Christianity did not immediately win the hearts and minds of the people of Europe. The process of Christianization was a slow one and, even toward the end of the Middle Ages, many people still practiced 'folk magic' and held to the beliefs of their ancestors even while observing Christian rites and rituals. The pre-Christian people – now commonly referenced as pagans – had no such label for themselves. The term pagan is a Christian designation from the French meaning a rustic who came from the countryside where the old beliefs and practices held tightly long after urban centers had more or less adopted orthodox Christian belief.

Even though there is ample evidence of Europeans in the Early Middle Ages accepting the basics of Christian doctrine, most definitely the existence of hell, a different paradigm of life on earth and the afterlife was so deeply ingrained in the communal consciousness that it could not easily just be set aside. In Britain, Scotland, and Ireland, especially, a belief in the “wee folk”, fairies, earth and water spirits, was regarded as simple common sense on how the world worked. One would no more go out of one's way to offend a water sprite than poison one's own well.

The belief in fairies, sprites, and ghosts (defined as spirits of the once-living) was so deeply embedded that parish priests allowed members of their congregations to continue practices of appeasement even though the Church instructed them to make clear such entities were demonic and not to be trifled with. Rituals involving certain incantations and spells, eating or displaying certain types of vegetables, performing certain acts or wearing a certain type of charm – all pagan practices with a long history – continued to be observed alongside going to Church, veneration of the saints, Christian prayer, confession, and acts of contrition.

A central concern of the Church, however, was right practice which reflected right belief, and the authorities struggled constantly to bring the population of Europe to this understanding. The problem, though, was that the rites of the Church did not resonate with a congregation like folk belief. The parish church or cathedral altar, at which the priest stood to celebrate the mass and transform the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ, was far removed from the congregation of onlookers. The priest recited the mass in Latin, his back to the people, and whatever went on up there at the front had little to do with the people observing it.

The baptismal font, therefore, became the focal point of church life as it was present at the beginning of one's life (through infant baptism), at confirmation, weddings, and funerals – even if it was not used at all of these events – and most notably for the ritual known as the ordeal (or Ordeal by Water) which decided a person's guilt or innocence.

The baptismal font was often quite large and deep and the accused would be bound and thrown into it. If the accused floated to the top, they were guilty of the charges while, if they sank, they were innocent. Unfortunately, the innocent had to enjoy exoneration post-mortem since they usually drowned. The ordeal was used for serious crimes in a community as well as charges of heresy, which included the continued practice of pre-Christian rites.

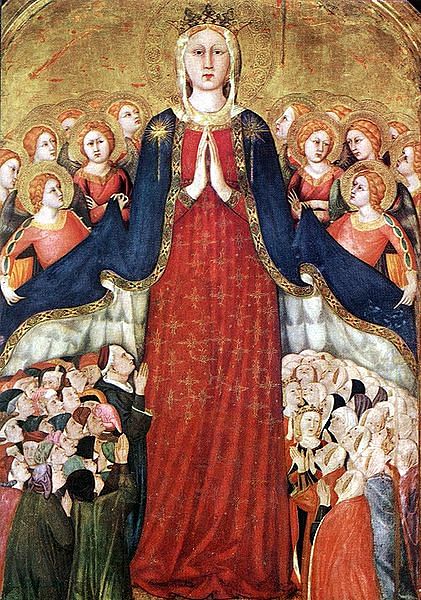

High Middle Ages & the Cult of Mary

The tendency of the laity to continue these practices did not diminish with time, threats, or repeated drownings. Just as in the present day one justifies one's own actions while condemning others for the same sort of behavior, the medieval peasant seems to have accepted that their neighbor, drowned by the Church for some transgression, deserved their fate. There is certainly no record of public outcry, and the ritual of the ordeal – like executions – were a form of public entertainment.

How the medieval peasant felt about anything at all is unknown as they were illiterate and anything recorded about their beliefs or behavior comes from Church or town records kept by clerics and priests. The peasants' silence is especially noted regarding the Church's view of women, who worked alongside men in the fields, could own their own businesses, join guilds, monastic orders and, in many cases, do the same work as a man but were still considered inferiors. As scholar Eileen Power observes, the peasants of a town "went to their churches on Sundays and listened while preachers told them in one breath that a woman was the gate of hell and that Mary was Queen of Heaven" (11). This view, established by the Church and supported by the aristocracy, would change significantly during the High Middle Ages (1000-1300), even though whatever progress was made would not last.

The Cult of the Virgin Mary was not new to the High Middle Ages – it had been popular in Palestine and Egypt from the 1st century onward – but became more highly developed during this time. Pope Gregory I (l. 540-604) established the two poles of womanhood in Christianity by characterizing Mary Magdalene as the redeemed prostitute and Mary the Mother of Jesus as the elevated virgin. Scholars still debate Gregory's reasons for characterizing Mary Magdalene in this way, conflating her with the Woman Taken in Adultery (John 8:1-11), even though there is no biblical support for his claim.

Mary Magdalene, linked through her sins to Eve and the Fall of Man, was the sexual temptress men were encouraged to flee while the Virgin Mary was beyond the realm of temptation, incorruptible, and untouchable. Actual human women might at one time be Magdalene and another the Virgin and, whether one or the other, were best dealt with from a distance. The Cult of the Virgin, however, at least encouraged greater respect for women.

At the same time the Cult of the Virgin was developing most rapidly (or possibly because of it) a genre of romantic poetry and an accompanying ideal was appearing in Southern France, known today as courtly love. Courtly love romanticism maintained that women were not only worthy of respect but adoration, devotion, and service. The genre and attendant behavior it inspired are closely linked to the queen Eleanor of Aquitaine (l. c. 1122-1204), her daughter Marie de Champagne (l. 1145-1198), and writers associated with them such as Chretien de Troyes (l. c. 1130-1190), Marie de France (wrote c. 1160-1215), and Andreas Capellanus (12th century). These writers and the women who inspired and patronized them created an elevated vision of womanhood unprecedented in the medieval period.

These changes occurred at the same time as the popularity of a heretical religious sect known as the Cathars was winning adherents away from the Catholic Church in precisely the same region of Southern France. The Cathars venerated a divine feminine principle, Sophia, whom they swore to protect and serve in the same way that the noble, chivalric knights in courtly love poetry devoted themselves to a lady. Some scholars (most notably Denis de Rougemont) have therefore suggested that courtly love poetry was a kind of code of the Cathars, who were regularly threatened and persecuted by the Church, by which they disseminated their teachings. This theory has been challenged repeatedly but never refuted.

The Cathars were destroyed by the Church in the Albigensian Crusade (1209-1229) with the last blow struck in 1244 at the Cathar stronghold of Montsegur. The crusading knights of the Church took the fortress after the Cathars' surrender and burned 200 of their clergy alive as heretics. The Inquisition, led by the order of the Dominicans, rooted out and condemned similar sects.

Islamic & Jewish Influences

The Cathars were not alone in suffering persecution from the Church, however, as the Jewish population of Europe had been experiencing that for centuries. Overall, relations between Jews and Christians were amicable, and there are letters, records, and personal journals extant showing that some Christians sought to convert to Judaism and Jews to Christianity. Scholar Joshua Trachtenberg notes how "in the tenth and eleventh centuries we hear of Jews receiving gifts from Gentile friends on Jewish holidays, of Jews leaving keys to their homes with Christian neighbors before departing on a journey" (160). Relations between members of the two religions were more or less cordial, in fact, until after the First Crusade (1096-1099).

Jews were forbidden to bear arms and so could not participate in the crusade, which seems to have upset their Christian neighbors whose husbands and sons were taken by the feudal lords off to the Holy Land. Economic hardships caused by lack of manpower to work the fields further damaged relationships between the two as many Jews were merchants who could continue their trade while the Christian peasant was tied to the land and struggled to plant, tend, and harvest a crop.

The First Crusade had the opposite effect on Muslims who, outside of Spain, had previously only appeared in Europe as traders. The crusade opened up the possibility of travel to the Holy Land, and a number of scholars took advantage of this to study with their Muslim counterparts. The works of Islamic scholars and scientists found their way to Europe along with translations of some of the greatest classical thinkers and writers such as Aristotle, whose works would have been lost if not for Muslim scribes. Jewish and Islamic scholasticism, in fact, contributed more significantly to the culture of Europe than any Christian efforts outside of the monasteries.

The Church's insistence on the absolute truth of its own vision, while condemning that of others, extended even to fellow Christians. The Catholic Church of the West quarreled with the Eastern Orthodox Church in 867 over who had the true faith, and the Eastern Orthodox Church finally broke all ties with its western counterpart in 1054, the so-called Great Schism. This was brought on by the Church's claim that it was founded by Saint Peter, was the only legitimate expression of Christian faith, and should therefore rightly be able to control the policies and land holdings of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Late Middle Ages & Reformation

In the Late Middle Ages (1300-1500), the Church continued to root out heresy on a large scale by suppressing upstart religious sects, individually by encouraging priests to punish heterodox belief or practice, and by labeling any critic or reformer a 'heretic' outside of God's grace. The peasantry, though nominally orthodox Catholic, continued to observe folk practices and, as scholar Patrick J. Geary notes, "knowledge of Christian belief did not mean that individuals used this knowledge in ways that coincided with officially sanctioned practice" (202). Since a medieval peasant was taught the prayers of the Our Father and Hail Mary in Latin, a language they did not understand, they recited them as incantations to ward off misfortune or bring luck, paying little attention to the importance of the words as understood by the Church. The mass itself, also conducted in Latin, was equally mysterious to the peasantry.

Consequently, the medieval peasant felt far more comfortable with a blending of the old pagan beliefs with Christianity which resulted in heterodox belief. Parish priests were again instructed to take heretical practices seriously and punish them, but the clergy was disinclined, largely because of the effort involved. Further, many of the clergy, especially the parish priests, were seen as hypocrites and had been for some time. One of the reasons heretical sects attracted adherents, in fact, was the respect generated by their clergy who lived their beliefs. In contrast, as Geary notes, the Catholic clergy epitomized the very Seven Deadly Sins they condemned:

The ignorance, sexual promiscuity, venality, and corruption of the clergy, combined with their frequent absenteeism, were major and long-standing complaints within the laity. Anti-clericalism was endemic to medieval society and in no way detracted from religious devotion. (199)

A parishioner could loathe the priest but still respect the religion that said priest represented. The priest, after all, had little to do with the life of the peasant while the saints could answer prayers, protect one from harm, and reward one's good deeds. Pilgrimages to saints' sites like Canterbury or Santiago de Compostela were thought to please the saint who would then grant the pilgrim favors and expiate sin in ways no priest could ever do.

At the same time, one could not do without the clergy owing to the Church's insistence on sacerdotalism – the policy which mandated that laypersons required the intercession of a priest to communicate with God or understand scripture – and so priests still wielded considerable power over individuals' lives. This was especially so regarding the afterlife state of purgatory in which one's soul would pay in torment for any sins not forgiven by a priest in one's life. Ecclesiastical writs known as indulgences were sold to people – often for high prices – which were believed to lessen the time for one's soul, or that of a loved one, in purgatorial fires.

The unending struggle to bring the peasantry in line with orthodoxy eventually relented as practices formerly condemned by the Church – such as astrology, oneirology (the study of dreams), demonology, and the use of talismans and charms – were recognized as significant sources of income. Sales of relics like a saint's toe or a splinter of the True Cross were common and, for a price, a priest could interpret one's dreams, chart one's stars, or name whatever demon was preventing a good marriage for one's son or daughter.

For many years, medieval scholarship insisted on a dichotomy of two Christianities in the Middle Ages – an elite culture dominated by the clergy, city-dwellers, and the written word, and a popular culture of the oral tradition of the rural masses, infused with pagan belief and practice. In the present day, it is recognized that pagan beliefs and rituals informed Christianity in both city and country from the beginning. As the Church gained more and more power, it was able to insist more stridently on people obeying its strictures, but the same underlying form – of the Church trying to impose a new belief structure on people used to the one of their ancestors – remained more or less intact throughout the Middle Ages.

Conclusion

As the medieval period wound to a close, the orthodoxy of the Church finally did permeate down through the lowest social class but this hardly did anyone any favors. The backlash against the progressive movement of the 12th century and its new value of women took the form of monastic religious orders such as the Premonstratensians banning women, guilds which had previously had female members declaring themselves men's-only-clubs, and women's ability to run businesses curtailed.

The ongoing crusades vilified Muslims as the archenemy of Christendom while Jews were blamed for practicing usury (charging interest) – even though the Church had more or less defined that role in finance for them through official policy – and were expelled from communities and entire countries. Pagan practices had now either been stamped out or Christianized, and the Church held significant power over people's daily lives.

The corruption of the medieval Church, however, against which critics and reformers had been preaching for centuries, finally grew too intolerable and general distrust of the Church and its vision was further encouraged by its failure to meet the challenge of the Black Death pandemic of 1347-1352 which resulted in a widespread spiritual crisis. The Protestant Reformation began as simply another attempt at getting the Church to pay attention to its own failings, but the political climate in Germany, and the personal power of the priest-monk Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546 CE), led to a revolt by people who had long grown tired of the monolithic Church.

After Martin Luther initiated the Reformation, other clerics followed his example. Christianity in Europe afterwards would frequently show itself no more tolerant or pure in Protestant form than it had been as expressed through the medieval Church but, in time, found a way to coexist with other faiths and allow for greater freedom of individual religious experience.