Illuminated manuscripts were hand-made books, usually on Christian scripture or practice, produced in Western Europe between c. 500-c. 1600. They are so called because of the use of gold and silver which illuminates the text and accompanying illustrations. Their production gradually died out after the invention of the printing press.

Although Muslim artisans also used this technique to ornament their books, the term “illuminated manuscripts” is most commonly used to refer to those works produced in Europe on Christian themes. However, the poetry and myth of pre-Christian authors, such as Virgil, was sometimes also illuminated.

Hand-made illuminated manuscripts were initially produced by monks in abbeys but, as they became more popular, production became commercialized and was taken over by secular book-makers. Illuminated manuscripts were quite costly to produce and only those of significant means could afford them.

The most popular type was the Book of Hours which was a Christian devotional of prayers to be said at certain times throughout the day. More Books of Hours have survived than any other work of the period simply because more of them were produced. The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in c. 1440 signaled the beginning of the end of hand-made books generally and illuminated manuscripts specifically.

A Brief History of Books

The written word was invented in Sumer, southern Mesopotamia, around 3500-3000 BCE, where clay tablets were used to convey information. The Egyptians began using papyrus scrolls by the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150-c. 2613 BCE) which were adopted by the Greeks and Romans, although these latter two also began to use writing tablets of wood covered with wax. Several such tablets could be bound together between covers of wood or metal to form a single volume; this was called a codex and it replaced the papyrus scroll in the Mediterranean region c. 400.

Paper was invented in China by Ts'ai Lun (also given as Cai Lun, 50-121 CE) during the Han Dynasty in c. 105 CE, and was introduced into the Arab world by Chinese merchants in the 7th century CE. The cities of Baghdad and Damascus, especially, became important centers of paper and book production and Muslim writers began producing original works of literature and poetry, as well as treaties on mathematics, science, astrology, and philosophy.

They also made extensive copies of western philosophers like Aristotle (384-322 BCE) which preserved many of his works long before they were appreciated in the west. Muslim artisans decorated their books with elaborate borders and illustrations and these are often defined as illuminated manuscripts.

In Europe, however, the acceptance of paper was still centuries away. The Chinese had been using paper for almost a century when people in Asia Minor developed writing surfaces made of animal hides (sheep or goats) which were soaked in water, scraped to remove hair, stretched on wooden frames to dry, and then bleached with lime; the finished product became known as parchment.

Parchment made of calfskin was called vellum, was of much higher quality as a writing surface, and so became more popular. European monks favored vellum and this became their standard material for the works which would become known as illuminated manuscripts. Paper and papyrus were considered un-Christian by the medieval church and their use was discouraged as these materials had been used by pagan writers in the past and were used by “heathens” of the east at this time. Paper would not be accepted by Europeans until the 11th century.

HOW THEY WERE MADE

As books became more popular, they were produced by secular merchants and sold in books stalls and stores. Initially, however, they were made by monks in monasteries, abbeys, and priories probably first in Ireland and then Britain and the continent.

Every monastery was required to have a library according to the rules of St. Benedict of the 6th century CE. Some books no doubt arrived with the monks who came to live there but most were produced at the site by monks known as scriptores in rooms called scriptoriums. From the 5th to the 13th century CE monasteries were the sole producers of books. The scriptorium was a large room with wooden chairs and writing tables which angled upwards to hold manuscript pages. Monks were involved in every aspect of a book's production from processing the vellum to the final product.

A director would distribute pages to be done to the monks in the room and then remain to supervise and maintain the rule of silence. Scribes worked only in the day and could not have candles or lamps near the manuscripts for fear of fire. The director would make sure that the monks remained at work, quietly, and continued until their pages were done. One monk rarely worked on a page to completion but rather traded with others in the room.

A monk would begin by cutting down a sheet of vellum to appropriate size. This practice would dictate the shape of books down to the present day as longer than they are wider. Once the vellum sheet was prepared, lines would be ruled across it for text and blank spaces left open for illustrations.

The text was written first in black ink (or gold or another appropriate color for the subject) between the ruled lines on the page and then would be given to another monk to proofread for errors; this second monk – or perhaps a third – would then add titles in blue or red ink and then pass the page on to the illuminator who would add images, color, and the requisite gold illumination. Monks wrote with quill pens and boiled iron, tree bark, and nuts to make black ink; other ink colors were produced by grinding and boiling different natural chemicals and plants.

The work was long and tedious, carried out in the silence of rooms lit only by narrow windows which were cold in winter and sultry in warmer weather. A scriptore-monk was expected to show up for work no matter the weather, their state of health, or interest in a project. It is clear, from brief comments written on some pages, that the monks were not always happy about their duties.

Scholar Giulia Bologna notes how many manuscripts include small notations written in the margins such as “This page was not copied slowly”, “I don't feel well today”, “This parchment is certainly hairy” and a long observation regarding having to sit for hours hunched over a writing table: “Three fingers write, but the entire body toils. Just as the sailor yearns for port, the writer longs for the last line” (37).

The Early Illuminated Manuscripts

The vellum works of Europe became the standard definition of a book for centuries. The word book comes from the Old English boc meaning 'a written document' or 'written sheet' and the texts produced on vellum in time came to be decorated with flourishes and illustrations. The earliest illuminated manuscript is the Vergilius Augusteus of the 4th century CE which exists in seven pages of what must have been a much larger book of Virgil's works.

It is not technically an illuminated manuscript because it makes no use of gold, silver, or any colored illustrations but it is the oldest European work which uses decorated capital letters to begin each page - a practice which would come to define illuminated manuscripts.

In the 5th century CE, the Ambrosian Iliad, an illuminated manuscript of Homer's work, was completed, most likely in Constantinople. This work is richly illustrated and the technique used seems to have influenced later artisans. The St. Augustine Gospels of the 6th century CE, another illuminated work, shows similarities to the earlier Iliad. The St. Augustine Gospels is a copy of the four gospels as translated by St. Jerome and was once completely illustrated but many of the pieces have been lost over time.

One of the most impressive of the early illuminated manuscripts is the Codex Argenteus ('Silver Book”) of the 6th century CE which is a copy of the Bishop Ulfilas' translation of the Bible (c. 4th century CE) into the Gothic language. The vellum pages were dyed purple, to denote the elevated subject matter, and the work was written and illustrated in silver and gold ink. It is commonly accepted that the book was produced for the Gothic king Theodoric the Great (r. 493-526 CE) in Italy.

FAMOUS ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPTS

The greatest works were created between the 7th – 16th centuries CE when the basics of illustration and decoration had been mastered and were perfected. Among these works, the best known is the Book of Kells, currently housed at Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland, created c. 800.

The Book of Kells was produced by monks of St. Columba's order of Iona, Scotland but exactly where it was made is uncertain. Theories regarding its composition range from its creation on the island of Iona, to Kells in Ireland, to Lindisfarne in Britain. It was most likely created, at least in part, at Iona and then brought to Kells to keep it safe from Viking raiders who first struck Iona in 795, shortly after their raid on Lindisfarne Priory in Britain.

A Viking raid in 806 killed 68 monks at Iona and led to the survivors abandoning the abbey in favor of another of their order at Kells. It is likely that the Book of Kells traveled with them at this time and may have been completed in Ireland. The grandeur of this work is justly praised but it should be noted that there are many other high-quality illuminated manuscripts currently housed in private collections, museums, and libraries around the world. Among these many, some of the most impressive are:

The Book of Durrow (650-700 CE) – The oldest illuminated book of the gospels created either at Iona or Lindisfarne Abbey. It contains a number of striking illustrations including carpet pages of intricate Celtic-knot motifs with various animals entwined.

Codex Amiatinus (c. late 7th – early 8th century CE) – The oldest version of St. Jerome's Vulgate Bible. It was created in Northumbria, Britain, and although it is not technically “illuminated” it does contain a number of significant full-page illustrations and miniatures.

Lindisfarne Gospels (c. 700-715 CE) – Among the best-known and most admired illuminated manuscripts, this work was created at the Lindisfarne Priory on the “Holy Island” off the coast of Dorset, Britain. It is an illustrated edition of the gospels of the New Testament made in honor of the priory's most famous member, St. Cuthbert.

The Morgan Crusader Bible (c. 1250 CE) – Created in Paris most likely for Louis IX (1214-1270 CE) whose piety was a defining characteristic of his reign. It was originally a work only of full-color illuminated illustrations of Old Testament events and lay subjects but later owners commissioned accompanying text to the images. The work is considered one of the greatest illuminated manuscripts and a masterpiece of medieval art.

The Westminster Abbey Bestiary (c. 1275-1290 CE) – Probably created in York, Britain, this work is a collection of descriptions of animals – some real and some imaginary – drawn from pre-Christian sources, the Bible, and legends. There were a number of bestiaries produced during the middle ages but the Westminster Abbey Bestiary is considered the finest for the skill of composition of the 164 illustrations it contains.

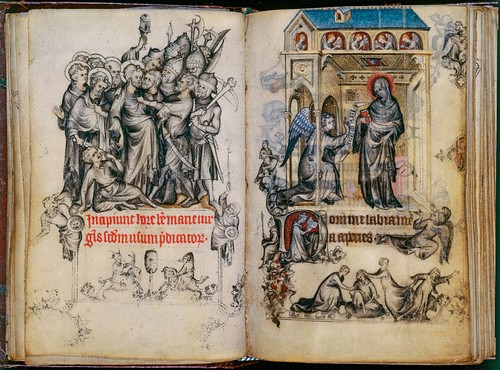

The Book of Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux (c. 1324-1328 CE) – Created in Paris, France by the leading illustrator of the time, Jean Pucelle, for the queen Jeanne d'Evreux (1310-1371 CE), wife of Charles IV (1322-1328 CE). It is a small Book of Hours delicately illustrated on exceptionally fine vellum with over 700 illustrations accompanying the text. The work is smaller than a modern-day paperback and must have required great skill to produce.

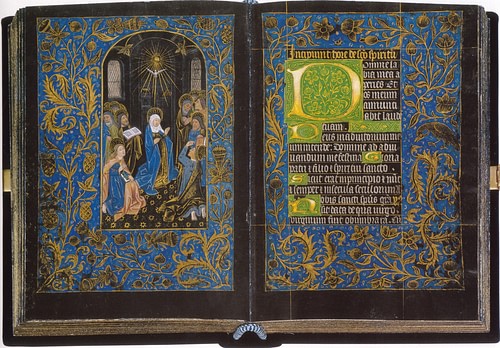

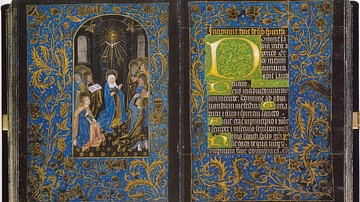

The Black Hours (c. 1475-1480 CE) – Created in Bruges, Belgium by an anonymous artist working in the style of the leading illustrator of the city, Wilhelm Vrelant who dominated the art from c. 1450 until his death in 1481 CE. It is made of vellum which was stained black and illuminated in striking blue and gold. The text is written in silver and gold ink. It is one of the most unique Books of Hours extant.

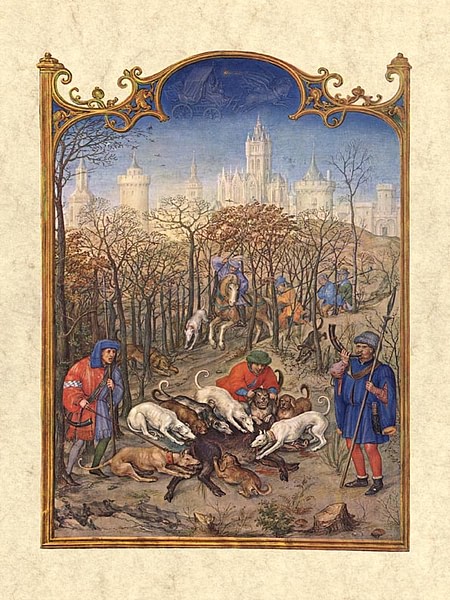

Les Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (c. 1412-1416 and 1485-1489 CE) – The most famous Book of Hours in the present day as well as its own time, this work was commissioned by Jean, Duke of Berry, Count of Poitiers, France (1340-1416 CE). It was left unfinished when the Duke as well as the artists working on it died of the plague in 1416 CE. The work was discovered and completed between the years 1485-1489 CE when it was recognized as a masterpiece. It is frequently referred to as the “king of illuminated manuscripts” because of the grandeur and intricacy of the paintings.

Grimani Breviary (c. 1510 CE) – An enormous work of 1,670 pages with full-page illustrations of scenes from the Bible, secular legend, contemporary landscapes and domestic scenes. The text is made up of prayers, psalms, and other selections from the Bible. It was probably made in Flanders but who created or commissioned it is unknown. The book was bought by the Venetian Cardinal Domenico Grimani (1461-1523 CE) in 1520 CE who declared it so beautiful that only select people of high moral standing should be allowed to see it and then only under special circumstances.

Prayer book of Claude de France (c. 1517 CE) – One of the most unique and impressive illuminated manuscripts, this book is small enough to fit in the palm of one's hand and yet is illustrated with 132 brilliantly realized works framed by elaborate and striking borders. The little book was made for Claude, queen of France (1514-1524 CE) along with a Book of Hours by an artist who was known, after completing these works, as Master of Claude de France.

The Printing Press & the End of Illumination

By the 13th century, literacy in Europe had improved and professional book-makers appeared on the scene in response to demand. In Britain, literature produced in vernacular languages had been encouraged since the reign of Alfred the Great (871-899) and, in France, since the time of Charlemagne (800-814). The greater demand led to the necessity for more scribes and many of these were women.

That both men and women were now involved in book production is clear from their known places of origin (such as nunneries rather than monasteries) as well as the same kind of notations the monks left on pages. Scholar Christopher de Hamel notes one such instance:

It is frequently said that women had an important role in promoting vernacular writing [English] because girls were not customarily taught Latin as thoroughly as boys. It is quite true that vernacular prayer books can often be traced to nuns rather than monks, for example…In fact the earliest dated Lancelot manuscript must have been written by a female scribe. It was made in 1274 and ends with the request that the reader will pray for the scribe, `pries pour ce li ki lescrist'; `ce li' is a feminine pronoun. (148)

Books continued to be produced by hand until the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in c. 1440. By 1456, he had printed the Latin Bible – now commonly referred to as the Gutenberg Bible – and the process of printing books instead of crafting them by hand was mastered.

Shortly after this, Gutenberg's press and equipment were seized for outstanding debts and Gutenberg's patron, Johann Fust, developed the printer's techniques successfully to mass produce written works. A single book of approximately 400 pages would have once taken at least six months to produce; now it could be printed in less than a week.

Even so, people then – as now – liked what they knew and many rejected the new product of the printed book. Giulia Bologna notes how "the great bibliophile Federigo da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, would have felt shame to have had a printed book in his library" (39). Printed books were at first considered cheap imitations of “real books” and printers, recognizing this, went to lengths to make them look like hand-made works of the past by binding them in leather, adding gold gilt to the covers, and hiring illustrators to provide images for the text. These practices helped make the new products more palatable to book collectors. Still, illuminated manuscripts were commissioned, though in far fewer numbers than in the past, up through the early years of the 17th century.

As the printed book became more widely accepted, however, the skills of illumination were valued less and less and eventually were forgotten. The work of the artists - most of them anonymous - would live on, however, in the books they had created. Illuminated manuscripts were intentionally crafted as valuable items from their beginning but became more so once they were no longer produced. The wealthy sought out these books and cultivated collections in their private libraries which preserved the works up through to the present day.