Massachusetts Bay Colony (1628-1691 CE) was the largest English settlement in New England and the most influential both in the colonization of the region and later developments in what would become the United States of America. It was founded and developed by Puritans, religious reformers who sought to 'purify' the policies and practices of the Anglican Church of Catholic influences, which put them in conflict with the Church and the Crown. When persecutions of Puritans became more intense in 1629 CE, many chose to leave and settle in North America where the successful Plymouth Colony had established itself in 1620 CE.

A preliminary expedition led by Puritan Separatist John Endicott (l. c. 1600-1665 CE) established a colony at Salem in 1628 CE, but a larger influx arrived in 1630 CE led by the Puritan lawyer John Winthrop (l. c. 1588-1649 CE). Winthrop arrived as the new governor with 700 colonists on four ships and the colony's center was moved from Endicott's village of Salem to a newly established site Winthrop named Boston.

As Massachusetts Bay Colony developed, it came into conflict with Native Americans of the region which resulted first in the Pequot War (1636-1638 CE) and then King Philip's War (1675-1678 CE), after which the colonists controlled the region and the natives who were not sold into slavery were moved to reservations or left the area.

Winthrop was primarily responsible for the vision and development of the colony for the first 18 years of its existence and it followed his model even after his death in 1649 CE. Events in England led to the revocation of the colony's charter, but it received a new one in 1691 CE under the name Province of Massachusetts Bay. At its height, it comprised parts of the present-day states of Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire. The form of government, cultural values, and policies of the colony would inform those of the region for years afterwards and, more or less, still do today.

Puritans & Separatists

The Protestant Reformation (1517-1648 CE) challenged, then rejected, the authority of the Catholic Church on theological grounds, but King Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547 CE) had no real interest in religious matters; he only wanted to divorce his wife and joined the Reformation when the Catholic Church prohibited this. Consequently, he made only minor changes to his new Anglican Church, the most significant being replacing the pope with the English monarch.

A number of theologians and religious reformers objected to this policy, especially after the reign of the Catholic Mary I of England (r. 1553-1558 CE), who restored Catholicism and persecuted Protestants, causing many to flee to Europe (becoming the so-called Marian Exiles). When these people returned under the reign of the Protestant Elizabeth I of England (1558-1603 CE), they had seen first-hand what true Church reform looked like elsewhere and sought the same for the Church of England. These people were referred to derisively by Anglicans as 'Puritans', which would equate to calling someone a 'stickler' or 'nitpicker' because, in the Anglican view, they criticized minor aspects of the Church which harmed no one. The Puritans referred to themselves by other names but, primarily, as 'Saints' because they felt they were practicing true Christianity based solely on the Bible which they interpreted as the literal word of God.

The Puritans wanted to complete the work of the Reformation by rejecting any Catholic elements still observed by the Anglican Church, but there were separatists among them, who felt the Church was wholly corrupt and could not be reformed. They maintained that a Christian must completely separate from the Church in order to serve God faithfully. Whether Puritan or separatist, both felt it their duty to criticize the Anglican Church through various (illegal) publications, to abstain from attending Anglican services (holding their own in private), and to live a life which marked them as true believers, apart from those they felt had been deceived by Satan through Anglican theology and practice.

Their beliefs and activities were outlawed as treasonous under Elizabeth I, and under her successor, James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE), Puritans were persecuted, many again fleeing to Europe. A group of separatists who had fled to Leiden, the Netherlands, decided to distance themselves further from James I's reach and, in 1620 CE, left to settle in North America.

Plymouth & Massachusetts Bay Colonies

These separatists established Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts, the first English colony in New England which not only survived but flourished. The Plymouth Colony was not a cohesive group of Puritan separatists, however, as half their number were so-called Strangers (people not of their faith), who were Anglican. The separatists (later referred to as pilgrims) had learned how to live with their Anglican shipmates aboard the Mayflower and had joined with them in signing the Mayflower Compact which established the colony's government; Plymouth was therefore somewhat ecumenical in daily, if not religious, life. Massachusetts Bay Colony, on the other hand, had a completely different demographic when it was founded and was comprised of Puritans governed by Puritans; they were, therefore, less tolerant of Strangers – and certainly of dissenters - than Plymouth.

News of the Plymouth Colony's success reached England in early 1622 CE, and in 1623 CE a small settlement was established at Cape Ann, which the investors hoped would turn a profit. After two years, and little to show for the effort and expense, Cape Ann Colony was abandoned but some of the colonists remained in the area. One of these, Roger Conant (l. c. 1592-1679 CE), was a former resident of Plymouth Colony who had moved to Cape Ann following a disagreement with Plymouth authorities. He established a new colony at the site of an abandoned native village just south of Cape Ann which he called Salem.

The Cape Ann colony was a purely commercial enterprise but the next attempt at colonization would not be. Between 1625-1629 CE, persecutions of Puritans grew worse under the reign of Charles I of England, and in 1628 CE, the newly formed Massachusetts Bay Company financed the expedition of an advance group of Puritans to New England. This group was led by John Endicott (l. c. 1600-1665 CE) who further expanded the Salem site between 1628-1630 CE. In 1630 CE, John Winthrop, who had been elected to replace Endicott as governor, led a fleet of four ships carrying 700 colonists in what has come to be known as the Great Migration (also Puritan Migration) to North America. Upon landing, he rejected Salem as the center of his new colony and chose another site, which he named Boston; this was the beginning of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, a charter colony (meaning it was granted the right to exist and form its own government by a legal charter from the English crown) comprised of the settlements of Boston, Cambridge, Charlestown, Dorchester, Medford, Roxbury, and Watertown.

Development & Vision

Winthrop worked alongside the other colonists to build the settlement while simultaneously organizing a system of government. Like Plymouth Colony, they established a representational form of government, a republic, in which magistrates were elected by popular vote. Although this government appeared democratic and stipulated a separation of church and state, it was closer to a theocracy because it was informed by Puritan values and only those who exemplified those values had a chance of being elected.

The colony was informed by Winthrop's vision of it as a 'city on a hill' which they were entrusted with establishing by God himself. Either just before the fleet left England in April of 1630 CE or during the crossing, Winthrop delivered his famous sermon A Model of Christian Charity in which he emphasized the importance of the colony's success, not just for those involved but for the propagation and even survival of Christianity itself and for God's honor and glory. He made clear that all the colonists would have to work together toward the common goal of success and, to do this, would have to be of like minds and be "knit together in this work as one man" (Hall, 169). Winthrop drew on the image from the biblical passage of Matthew 5:14 in which Jesus Christ tells his followers "You are the light of the world. A city that is set upon a hill cannot be hidden" to impress upon the colonists the importance of the work they had before them:

For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us; so that if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken and so cause him to withdraw his present help from us, we shall be made a story and a by-word through the world, we shall open the mouths of enemies to speak evil of the ways of God and all professors for God's sake; we shall shame the faces of many of God's worthy servants, and cause their prayers to be turned into curses upon us till we be consumed out of the good land whither we are going. (Hall, 169)

The sermon had the desired effect of establishing a colony of single-minded Puritans who, more or less, would continue to work together over the next few years to establish a successful settlement. Fewer colonists of Massachusetts Bay died the first year than any other English colony founded prior to 1630 CE. The Jamestown Colony of Virginia lost over half their population between 1607-1608 CE and over 80% before 1610 CE. The Plymouth Colony also lost half their population the first year and the earlier Popham Colony (1607-1608 CE), though it had no high casualty rate, was abandoned after 14 months. The Massachusetts Bay Colony was thriving after the first year through agriculture and trade (primarily in fur and lumber at first) and later through industries such as shipbuilding.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony had a tighter cohesion than others because of their common vision, and this led to greater productivity. Plymouth Colony, although successful, did not share in this attribute since the citizens were not all Puritans. Disagreements on policy and punishment were fairly common at Plymouth, but not so much at Massachusetts Bay Colony. Throughout the two colonies' histories, Plymouth would be the more tolerant and welcoming while, in order to maintain Winthrop's vision, Massachusetts Bay would rid itself of anyone who challenged the established order or did conform to the colony's beliefs, values, and accepted forms of behavior.

Dissent & Banishment

The Puritans had come to North America to establish a colony where people could worship God freely; as long as the people believed and worshipped as they did. The first source of conflict and dissent they dealt with was a man who was not even part of the colony. In 1630 CE, shortly after arriving, Winthrop presided over the trial and banishment of the liberal Anglican lawyer Thomas Morton (l. c. 1579-1647 CE), leader of the nearby Merrymount Colony, whose views on religion and proper behavior differed sharply from those of the colony. Morton was exiled back to England where he then pursued legal action to strip Massachusetts Bay Colony of its charter.

He won the lawsuit, but it was a meaningless victory because Winthrop had had the foresight to take the original charter with him when he left England, and when Morton won, the authorities were too busy with other matters to expend any efforts sending a delegation to North America to take it back. Although England had registered the charter, they did not have the original nor the colony's board. Winthrop's possession of both meant that the authority of the magistrates to govern the colony was in their hands, not back in England where the king could interfere, and it was physical proof of their legal right to colonize and govern the region as best as they saw fit.

This being so, Winthrop and the others felt no need to tolerate challenges to their authority. In the 1630s CE, the unity of the colony was tested by various dissenters who were banished for defying Winthrop's vision and proposing reform. Among the best known of these dissenters were Roger Williams (l. 1603-1683 CE), Anne Hutchinson (l. 1591-1643 CE), Thomas Hooker (l. 1586-1647 CE), and John Wheelwright (l. c. 1592-1679 CE). Hutchinson, Hooker, and Wheelwright were the primary instigators of the Antinomian Controversy ("against the law") which challenged the concept of one's personal efforts affecting one's salvation.

They claimed the Puritans were emphasizing adherence to the spirit of the law in religious practice rather than relying on God's free grace. The Puritans believed in predestination – God had already decided who was to be saved or damned – but felt one should live one's life in the hope of salvation, and this included performing works worthy of God's approval. Hutchinson and the others claimed there was nothing one could do to merit God's grace and charged Winthrop and the others of anti-biblical policies and practices.

Williams claimed, among other criticisms, that, since everyone was a sinner, no one was worthy to partake in communion, and, as a pastor, he denied more and more colonists communion until only he and his wife were allowed, then only him, until he finally realized he was also a sinner and unworthy. All of these reformers were banished from the colony after arrest and trial. Williams, Hutchinson, and Wheelwright would leave to colonize the regions which became Rhode Island and New Hampshire while Hooker established Connecticut.

Conclusion

Although these dissenters disagreed with how the Puritans were practicing their faith, they were still intensely religious, anti-Catholic, Protestant Christians who believed in the Great Commission (spreading the Christian message through evangelization), and the colonies they established reflected this belief. Every colony in New England, to greater or lesser extents, engaged in missionary work to the Native Americans whom they believed were not only in need of civilization and salvation but had somehow spiritually asked the Puritans to come and help them toward these goals.

Between 1630-1640 CE, 20,000 more colonists would arrive in New England, taking more land as they expanded outward from the established settlements. Although Plymouth Colony also believed in the importance of spreading the Christian message to the Native Americans, they were less zealous – at least initially – than Massachusetts Bay Colony and also, in their early years, pursued no expansionist policies. Massachusetts Bay Colony, therefore, was the primary colonizer of the rest of New England either intentionally or through the banishment of dissenters.

The expansion of the colony brought the settlers into conflict with the Native Americans of the region. Winthrop's Indian policy held that, first of all, God had cleared the land of natives between c. 1600-1620 CE through disease in order to make settlement by his chosen people easier and, second, that since the natives did not fence off their lands or appear to make the most of them, any land without an actual Native American settlement on it was free for the taking by any colonist.

This policy led to the practice of colonists taking more and more land without offering any form of payment or offering a token payment less than what the land was worth which was accepted by the natives who had no concept of private land ownership or sale. To a Pequot, for example, 'sale' seemed the equivalent of 'rent' or 'borrow' and any payment that changed hands was regarded as a gratuity, not as a transaction for permanent sale.

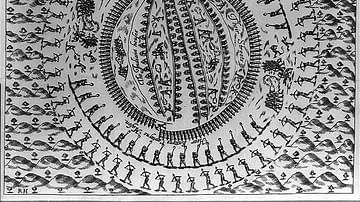

Misunderstandings, greed, religious intolerance, and simple racism eventually led to the outbreak of the Pequot War between 1636-1638 CE, which was decided in favor of the colonists after the Mystic Massacre of 1637 CE in which over 700 Pequot, mostly women and children, were slaughtered in their fortified village by colonist militia. Afterward, Pequot survivors were sold into slavery either on nearby plantations or in the West Indies. The slave trade, whether dealing in Native American or African slaves, was a significant source of income for the colony, which also operated a lucrative trade in salted fish which were sold to plantations in the south and West Indies to feed their slaves.

King Philip's War between 1675-1678 CE broke out when the chief of the Wampanoag Confederacy, Metacom (known to the colonists as King Philip, l. 1638-1676 CE), could no longer tolerate the many broken treaties with Massachusetts Bay Colony and the continual land theft which pushed his people further and further into the interior. After Metacom was killed and the war won by the colonists, New England was controlled by the colonies and the natives were either moved to reservations or left the area.

Throughout the first 20 years of the colony, England had been engulfed in the conflict of civil wars, the abolition of the monarchy and rise of the Commonwealth, the establishment of the Puritan Protectorate, and other problems, but in 1686 CE, James II of England (r. 1685-1688 CE) turned his attention to the colonies and revoked the charter in order to blend Massachusetts Bay Colony with others as the Dominion of New England. In 1691 CE, a new charter was obtained designating the colony the Province of Massachusetts Bay and incorporating other settlements in Massachusetts, notably Plymouth Colony, into it. The province would in time become the modern-day State of Massachusetts, with its capital at Boston, which would continue to adhere to the Puritan vision, with modifications, up through the 19th century CE and, in some respects, into the present day.