The Mayflower is the name of the cargo ship that brought the Puritan separatists (known as pilgrims) to North America in 1620 CE. It was a type of sailing ship known as a carrack with three masts with square-rigged sails on the main and foremast, three decks (upper, gun, and cargo), and measured roughly 100 feet (27 m) long and 25 feet (7 m) wide. The pilgrim passengers, and those not affiliated with the group, were quartered on the gun deck (also known as the Tween Deck as it was in-between the other two) which, with the 8 small cannons, 4 medium cannons, and other considerations, was reduced to a living space of roughly 70 feet (21 m) overall. The 30 or so crew members and captain quartered on the upper deck in the forecastle and aft castle, which also held pens for animals. Goods for the voyage were stored in the cargo hold, and passengers traveled in the tween. There were no windows on the tween deck and the ceiling was only 5 feet (1.5 m) high, with no latrines and no private rooms; these were the living conditions for the 102 passengers on their journey from 6 September to 11 November 1620 CE.

The captain and quarter-owner of the Mayflower was Christopher Jones (l. c. 1570-1622 CE) who commanded a crew of 30 men and was contracted by one Thomas Weston (l. 1584 - c. 1647 CE) in the interests of the Puritan separatists living in Leiden, the Netherlands, to transport them to the New World to found their own settlement. The English colony of Jamestown, Virginia was thriving and their original destination was north of Jamestown, just below the Hudson River Valley in the region of present-day New York State, which was then part of the English Virginia Patent, but weather and lack of supplies forced their landing in present-day Massachusetts at Plymouth.

The pilgrims under John Carver (l.c. 1584-1621 CE), Edward Winslow (l. 1595-1655 CE), and William Bradford (l. 1590-1657 CE), and the others not of their group, signed the Mayflower Compact upon their arrival at Plymouth, a set of laws all agreed to live by which would inform those that came later and established the Plymouth Colony (1620-1691 CE), which would eventually become absorbed by the Massachusetts Bay Colony, forming the basis of present-day New England in the United States.

The Puritan interpretation of Christianity would influence the development of that religion in the early English North American colonies and the later United States and continues to through the present day. The Plymouth Colony also has provided the United States with some of its most enduring cultural myths, referenced annually in November through the celebration of Thanksgiving since the 19th century CE.

Pilgrim Origins

The pilgrims who subjected themselves to the Atlantic crossing on the Mayflower were religious separatists whose beliefs were inspired by the Protestant Reformation (1517-1648 CE) in its earliest years and, especially, the theology of Jean Cauvin (better known as John Calvin, l. 1509-1564 CE) the French philosopher, theologian, and reformer whose interpretation of Christianity informs Congregationalist, Presbyterian, and Reformed sects of Protestant Christianity in the modern era. The immediate source of their belief was Brownism, based on the teachings of Robert Browne (l. 1550-1633 CE), an Anglican priest who became disillusioned with the Church of England's practices and sought to establish a separate church rather than attempt reform of what he saw as false teachings.

The Anglican church (also known as the Church of England) was established by King Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547 CE) after he broke from the Catholic Church but still retained many aspects of Catholicism which fundamentalist Protestant Christians rejected, such as vestments for clergy, kneeling at the name of Jesus, calling a priest “father”, organ and choral music as part of worship, and especially the liturgy of the Book of Common Prayer. Browne, and those of like minds, believed one should be able to pray to God in any way the Holy Spirit directed and that there should be no “guidebook” or set times for prayer. Further, they rejected the concept of a governing body of the Church, arguing instead that each church should be an independent entity – modeled on the early Christian community from the biblical Book of Acts – able to decide on its own form of worship, prayer, and ritual without consulting with any authority except God through the revealed scriptures.

By the time Browne was advocating this vision, the Church of England was no longer a Protestant sect but an established institution with a hierarchy, cathedrals, churches, and set liturgy in place, and it persecuted separatists in the same way the Catholic Church had earlier with Protestants. Separatists could be and were arrested, imprisoned, and executed, which led many to leave England and settle in the Netherlands which had more lenient views of religion and encouraged tolerance for different beliefs.

Persecution & Exodus

In 1607 CE, the Anglican Archbishop Tobias Matthew (l. 1546-1628 CE), authorized raids on the homes of separatists in the village of Scrooby, England, where the congregation of pastor John Robinson (l. 1576-1625 CE) worshipped and arrested a number of them. The following year, Robinson and William Bradford led their people to the Netherlands, establishing themselves first in Amsterdam and then at Leiden. James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE) was not only the reigning monarch but also head of the Church of England who empowered the clerics with the right under the law to persecute separatists and others who caused dissension. He initiated talks with the government of the Netherlands to have the Leiden congregation repatriated to England or be allowed to come and collect them, and these requests were granted as the separatists were known as religious elitists and troublemakers on the secular level.

In 1618 CE, the spiritual mentor of Robinson and one of the most highly respected members of the Leiden congregation, William Brewster (l. 1568-1644 CE), published a tract highly critical of the king and his church, which brought English authorities with orders to arrest him. The congregation hid Brewster but understood they needed to take drastic measures to distance themselves from James I's reach.

The lives of Bradford and the others in Leiden was far from satisfactory anyway. Their congregation had been labeled “seditious” and was suspect, and further, as foreigners in a land controlled by guilds favoring citizens, they could only hold the lowest-paying jobs. Bradford had been a wealthy landowner in England; in Leiden, he could only find work as a weaver. They understood their best chance of living their faith freely was to obtain a charter to establish a colony in North America, but there was no way the authorities of James I would grant them one.

There was a way around this, however, by appealing to a wealthy investor's religious sentiment and greed. The English colonization of North America was initiated by Queen Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603 CE) through Sir Walter Raleigh (l. c. 1552-1618 CE) but was inspired by the writings and ideology of Richard Hakluyt (l. 1553-1616 CE), a founding member of the Virginia Company of London responsible for the Jamestown Colony's establishment in 1607 CE. Hakluyt emphasized the spiritual obligation of Christian Europe to colonize North America for the salvation of the natives who had never heard the scriptures and required salvation. His works encouraged many to invest in colonization efforts as a kind of offering to God, and if it were God's will that they should make a 100% return on their investment, that would just be God's way of thanking them for their generosity and altruism.

The evangelical justification for colonization gave rise to middlemen (known as merchant adventurers) willing to solicit funds for an expedition to the New World after the success of the tobacco crop of Jamestown had made so many shareholders of the Virginia Company millionaires and, of course, after so many Native Americans had been "saved" through conversion, after 1611 CE. Among these was Thomas Weston (l. 1584 - c. 1647 CE) who put together a joint-stock venture for the Virginia Company to finance the Leiden congregation's exodus from the Netherlands to the Americas, negotiating with two members of the congregation, Robert Cushman (l. 1577-1625 CE) and John Carver.

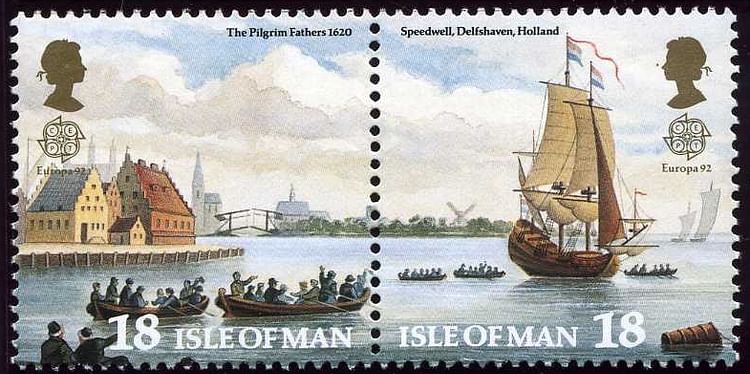

Weston financed the trip on the understanding that the colonists would work six days a week and none would own their own land or home as all profits were to be returned to the investors until their debt was paid. A friend (or member) of the congregation, one Captain Blossom, purchased them the passenger ship called the Speedwell and Weston rented another, larger cargo ship, the Mayflower and, in July 1620 CE, they went to the port town of Delftshaven to the Speedwell, having already decided that only the youngest and strongest would make the first voyage; the others would be sent for later.

They took the Speedwell to England in July 1620 CE and found the Mayflower waiting for them at the docks of Southampton. Weston had procured the services of Captain Christopher Jones and his crew to take the passengers. Jones made his money, primarily, in piloting the Mayflower between England and France trading textiles for wine but was an experienced captain on the open sea. The pilgrims loaded what goods they could take (one single box of all their possessions for most of them) and boarded the ships for the New World in July 1620 CE.

The Passengers

The Speedwell was found to be leaking and significantly delayed the journey as both ships had to stop and await repairs. Two more times the company started off but the Speedwell was leaking too badly to continue. Finally, the decision was made to leave it behind, along with many of its passengers, but 20 of them were welcomed aboard the Mayflower, and they began again across the Atlantic in September.

In addition to the congregation, a number of Strangers (those not of the faith) would be making the trip in order to help the pilgrims turn a profit once they arrived. Among these was Captain Myles Standish (l. c. 1584-1656 CE) who was to serve as a military consultant should the colonists have any problems with the Spanish, French, or indigenous people of the region. Among the other memorable names of passengers is John Alden (l. c. 1598-1687 CE), a cooper and member of the crew who made barrels for the colonists, and Pricilla Mullins (l. c. 1602-1685 CE), a member of the congregation and, later, Alden's wife, immortalized in the historical fiction The Courtship of Miles Standish by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (l. 1807-1882 CE), one of their descendants.

Richard Warren (l. c. 1578-1628 CE), another Stranger, traveled alone on the Mayflower, leaving his wife, Elizabeth, and five daughters back home to wait for the second trip. In all, they would have seven children all of whom, against the odds, lived to adulthood. Among their descendants are a number of notable individuals including author Ernest Hemingway, presidents Ulysses S. Grant and Franklin D. Roosevelt, author Laura Ingalls Wilder, and other notable figures from United States history.

Stephen Hopkins (l. 1581-1644 CE) was one of the survivors of the shipwreck of the Sea Venture in Bermuda bringing supplies in Jamestown in 1609 CE, traveled to Jamestown afterwards and assisted in the organization of the settlement, returned to England, and then traveled back to the New World on the Mayflower with his second wife, three children, and two servants. His son, Oceanus Hopkins, was born on the Mayflower but died seven years later.

William Brewster traveled with his wife Mary and their children and would be among the very few to survive the first winter and, in fact, live past the age of 60 in the colony. John Carver, like Brewster, was another member of the congregation who helped negotiate funding for the expedition and was elected the first governor of the colony; William Bradford would become the second governor and chronicler of the Plymouth Colony.

These are only a few of the 102 passengers and approximately 30 crew members aboard the Mayflower, which was around twelve years old at the time, not built for passenger service, and used mostly for short turn-around trade voyages between England and France. It would hold its own on the open seas but the voyage would not be easy nor pleasant. The Atlantic Ocean was especially rough in the autumn months and, having taken aboard the passengers of the Speedwell, provisions would be limited. Even so, there is no record of any of the passengers hesitating even though the trip meant living below deck in dim light, no privacy, and with no promise they would ever reach their destination.

Voyage & First Winter

The trip began calmly with good winds and a calm sea but grew increasingly difficult the further they traveled. The seas were rough with waves sometimes towering high over the ship and crashing against the sides, but they only lost two people (both to disease), one of the crew and a servant of the doctor Samuel Fuller (l. c. 1580-1633 CE). John Howland (l.c. 1592-1673 CE), one of John Carver's servants, was swept overboard but saved himself by clinging to a rope until he was rescued by crew members. Scholar Rebecca Fraser comments on the trip:

The journey lasted just over two months. From between decks where the passengers lived, they could see [through the gunwales] and smell the sea and hear the dash and smash of the waves…to travel on such a perilous journey required the greatest trust and confidence in one another. (45)

They arrived at modern-day Provincetown Harbor toward the northernmost tip of Cape Cod in the cold of 11 November 1620 CE. The pilgrims had purchased maps made by Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631 CE) of Jamestown fame, who had also traveled to and mapped this area, and they had hoped to reach the final destination of the Hudson Valley or Virginia, but a lack of supplies, and the prospect of more rough seas and dangers, persuaded them to settle here, across the bay from where they had first sighted land, at a place named New Plimouth by John Smith, present-day Plymouth, Massachusetts.

Before dropping anchor or making preparations for going ashore, they composed and signed the Mayflower Compact, an agreement between the puritan pilgrims and the Strangers to abide by common laws in the new colony for the collective good of all. It was signed by 41 of the male passengers aboard, and then the anchor was released, and they lowered the boats for shore.

Once on land, the puritan pilgrims led the others in a service of gratitude to God for their safe passage and the prospect of a successful colony in what they regarded as a “New Jerusalem” where they could worship and live freely without fear of persecution. The weather was much colder than they had anticipated, and they spent the first night with little shelter, wet from the sea, in near-freezing conditions. They soon realized that the New World was nothing like they had expected. The so-called First Encounter they had with natives was hostile and they had arrived too late to plant any crops and so had no way of procuring food other than taking what they found from deserted Native American villages.

By the time the first winter was over, the pilgrims had lost over 50% of their people and Captain Jones' crew was equally reduced. Small huts were built for shelter but many of the pilgrims wintered aboard the Mayflower where disease spread easily while those who remained ashore often succumbed to the cold. None of the party would have survived without the intervention of the Native American Tisquantum (better known as Squanto, l. c. 1585-1622 CE) of the Patuxet tribe and Samoset (also given as Somerset, l. c. 1590-1653 CE) of the Abenaki who introduced the pilgrims to Ousamequin (also known by his title Massasoit Sachem, l. c. 1581-1661 CE), chief of the Wampanoag Confederacy, who would assist them further.

Squanto was the last of his tribe since most had been killed by disease brought by the European settlers who founded the Popham Colony in the region of present-day Maine in 1607 CE and then furthered by others arriving between then and 1614 CE some of whom, such as the notorious Captain Thomas Hunt, made the situation worse by kidnapping as many natives as he could and selling them as slaves in the West Indies. Squanto had been one of these but had escaped to England and knew the language and so was able to instruct the pilgrims in how to grow the staples of corn, beans, and squash, which enabled the survivors of the first winter to continue on and establish the colony. He would die of the same European-borne diseases that had killed the rest of his tribe two years after the pilgrims arrived.

Conclusion

The pilgrims survived, however, and would celebrate their arrival in the New World and all the Native Americans had done for them with a feast on the one-year anniversary of their arrival in autumn of 1621 CE. Captain Jones had long since left for England by then, and the pilgrims had built themselves homes and established crops to keep them alive through the next winter. This first feast, mentioned by Bradford and Winslow, would later be institutionalized as the United States' national holiday of Thanksgiving by President Abraham Lincoln (served 1861-1865 CE).

Captain Christopher Jones died in 1622 CE after returning from one of his trade runs to France, and the Mayflower then lay at anchor in the port at Rotherhithe-on-Thames for two years as it steadily rotted. In 1624 CE, it was sold as scrap for approximately 130 pounds, which was divided between the other owners and Jones' widow. According to traditional accounts, parts of the ship were used to build the so-called Mayflower Barn in Buckinghamshire, England but this claim has been repeatedly challenged. Whatever the final fate of the Mayflower's remains, however, its name lives on as the iconic ship that brought the pilgrims to the New World to establish their vision of a land of promise where one could live and worship freely.