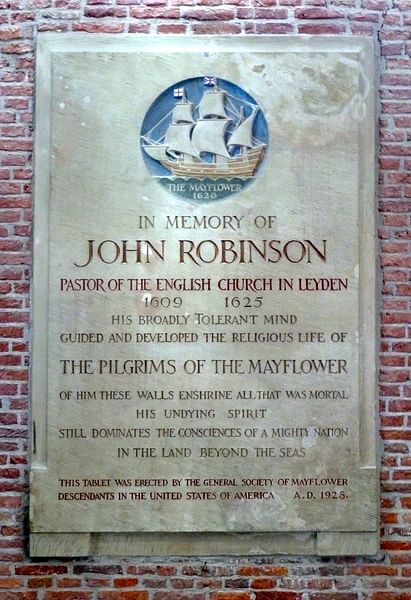

John Robinson (l. 1576-1625 CE) was the pastor of the Leiden congregation of separatists, some of whom made up the party (later known as pilgrims) who sailed on the Mayflower in 1620 CE to establish the Plymouth Colony in North America. Robinson was a former Anglican theologian, educated at Cambridge, who became convinced that the Anglican Church was corrupt and at first embraced the Puritan efforts at reform prior to abandoning them and becoming a separatist, advocating for separation from the church and the establishment of individual congregations.

He first became involved with the congregation in Scrooby, England and led them to Leiden, the Netherlands in 1607 CE, where he purchased a plot of land known as the Green Gate and helped establish a separatist community there. Along with William Brewster (l. 1568-1644 CE), he enlarged the congregation, defended separatist beliefs against attacks (real or perceived) from the Anglican Church and the Dutch Reformed Church, and supported Brewster's call for the congregation to relocate to North America.

He is credited with providing the model for the Mayflower Compact which is thought to have been based on the covenant he wrote up for his church and influenced by his farewell letter to the Mayflower passengers in July of 1620 CE. Robinson planned on joining the colonists in the second wave of immigrants, but his responsibilities to the members who had remained behind delayed him, and he died in 1625 CE.

His letters to the governors John Carver (l. 1584-1621 CE) and William Bradford (l. 1590-1657 CE) influenced their policies in the new colony, and he is especially remembered for taking the side of the Native Americans in disputes with the colonists and advocating for peaceful relationships between immigrants and natives. He is honored both in Leiden, the Netherlands, and Massachusetts, USA, for his contributions to the cause of religious freedom, peaceful coexistence, and encouraging the Plymouth Colony to honor their treaty with the Wampanoag Confederacy.

Early Life & Conversion

Little is known of Robinson's early life. He was born at Sturton-Le-Steeple in Nottinghamshire, England in 1576 CE, was enrolled at Cambridge University in 1592 CE, and graduated in 1596 CE, afterwards becoming a priest of the Anglican Church. He was fluent in Greek and Latin and regarded as a promising scholar and cleric at this time, but he came to sympathize with and then embrace the Puritan vision which was popular among the student body of Cambridge.

The term “Puritan” was originally coined by detractors in referencing those who objected to policies and practices of the Anglican Church and wished to purify it of any traces of Roman Catholicism. Although the Anglicans had broken with the Catholic Church under Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547 CE), it still retained aspects of Catholicism in worship services, hierarchy, administration, and personal devotion. Puritans especially objected to the mandatory use of the Book of Common Prayer which stipulated set prayers and recitations, which believers were encouraged to follow.

Puritans believed one should be free to express one's self to God in prayer in one's own words and claimed that the Book of Common Prayer prevented this by forcing people to recite “dead words” on a page rather than giving voice to one's own needs and concerns. Robinson would eventually break with the Anglican Church and even with fellow Puritans, becoming a separatist in his belief that the Church was too corrupt to be purified and one's only honest recourse as a believer was to join with others who recognized the Bible as the only spiritual authority and form independent congregations. The Book of Common Prayer was a major point of contention with him. According to scholar George F. Willison:

Robinson [denounced] the use of set prayers, even the Lord's Prayer. Anybody could read a prayer. It was altogether as puerile a performance as for a child “to read of a book or a prayer (saying), Father, I pray you give me bread, or fish, or an egg”. (104)

Robinson embraced the separatist vision of the former Anglican priest turned reformer Robert Browne (l. 1550-1633 CE) whose followers were known as Brownists but, at first, did not want to leave the Anglican Church. This could have been out of fear of legal reprisals since James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE) was the head of the Church and encouraged persecution of religious dissenters under The Act Against Puritans which had become law under Elizabeth I of England (r. 1559-1603 CE). It is equally possible, however, that he was reluctant to abandon the Church because it was the only spiritual home he had ever known.

He held a number of prominent positions as an Anglican cleric through 1604 CE when he was finally persuaded by his friend and former Anglican priest, John Smyth (l. c. 1554-1612 CE), that the Church could not be purified and was too corrupt to provide spiritual guidance. By 1606 CE, had joined a separatist congregation at Scrooby, England influenced by the teachings of the Brownist pastor Richard Clyfton (d. 1616 CE) and organized by William Brewster who held secret services at his home.

Leiden & Relocation Efforts

In 1607 CE, the congregation was discovered by agents of the Anglican Church, and many were imprisoned or fined. Brewster organized the group to relocate to Leiden, the Netherlands, where the government practiced a policy of religious tolerance. The group's first attempt to escape England failed when the Anglican captain of the ship they had chartered betrayed them to authorities, and their second attempt was also thwarted, but eventually, most of the congregation arrived in Amsterdam and then settled at Leiden.

Robinson, as the most highly educated and the only member holding a degree in theology, was elected pastor and then furthered his education by enrolling at the University of Leiden (a status which also would afford him the legal protection against religious persecution granted to students and faculty under intellectual freedom of speech, probably his main motive). He purchased a lot known as the Green Gate and invested in low-income housing for members of the congregation to be built around his home which served as the center of worship.

Although the congregation was now free to practice their faith as they wished, they suffered financially because jobs in the Netherlands were controlled by guilds, and as foreigners, they were ineligible to join and forced to accept the lowest-paying jobs as menial laborers. Further, the congregation began to be concerned for their children who were assimilating into Dutch culture and seemed to be losing their English heritage. By 1617 CE, they were already looking into relocating elsewhere, and Brewster advocated establishing their own colony in North America where they could live according to their beliefs while still retaining their cultural identity. Robinson supported the move and two members, Robert Cushman (l. 1577-1625 CE) and John Carver were sent back to England to arrange transport and provision for the voyage.

Brewster was originally chosen to lead negotiations as he had the most experience both as a businessman and former assistant to a diplomat, but in 1618 CE, he published an anti-Anglican work through the press he had established, which resulted in orders issued for his arrest. Brewster went into hiding, and it was already clear that efforts needed to be increased to relocate the congregation when Robinson contributed to their troubles by publishing a tract criticizing the Dutch Reformed Church in response to rumors that it had become critical of the separatist movement. Willison writes:

If Robinson had set out deliberately to make matters worse, he could scarcely have done as well as he did. His usual discretion and good sense deserting him in his anger, he bluntly attacked the hierarchical structure of the Dutch church with its synods, assemblies, and other central governing agencies, citing against it the “true” Brownist principle of independent congregations, each a church in itself and accountable to no higher authority, cooperating with sister churches in a purely voluntary fellowship. (104)

Afterwards, the congregation could expect no help or sympathy from the Dutch Reformed Church, were already being monitored by the agents of the Anglican Church who were hunting for Brewster, while they continued to suffer financially in their low-paying jobs. Cushman and Carver stepped up their efforts and secured a deal with the merchant adventurer Thomas Weston (l. 1584 - c. 1647 CE) for passage to North America. The congregation purchased (or had purchased for them) the passenger ship the Speedwell, and Weston rented them the cargo ship, the Mayflower, with the original deal stipulating that only the members of the congregation would take passage, and once arrived in North America, they would only be required to work for the Virginia Company, which was financing the expedition, four days a week, the other two to be used for the colonists' own profit and the sabbath as a day off.

Weston changed the terms of the deal shortly before they were to leave, however, as he came to believe that the separatists were too inexperienced to establish a profitable colony. There would now be a number of Anglicans (whom the separatists referred to as Strangers, those not of their faith) accompanying them, and they would have to work for the company six days a week in order to repay their debt. Cushman agreed to these changes without consulting with Robinson or the rest of the congregation, which earned him the later criticism of many, including Bradford whose Of Plymouth Plantation provides the details of the negotiations and critique of Cushman's part in them.

Influence on Mayflower Compact

Robinson accompanied the members of the congregation who would be leaving to the port of Delfthaven where he delivered a parting sermon to encourage them. He remained behind to minister to the remaining congregation and established William Brewster, who had returned from hiding for the journey, as their pastor until he could come later. The Speedwell sailed to Southampton with around 35 members of the congregation to meet up with others, the Strangers, and the Mayflower in July 1620 CE, and the two ships departed for the New World together. The Speedwell leaked, however, and had to be abandoned, necessitating a number of its passengers to then board the Mayflower for the transatlantic crossing in September 1620 CE.

The Mayflower was supposed to land in Virginia, where the Jamestown Colony was already established in 1607 and English law was in place, but was blown off course and landed in New England. Their patent was invalid in this region, and according to Bradford, a number of the Strangers argued that each passenger should be allowed to live as he pleased, without constraint, since there was no law to compel them to do otherwise. This dispute was resolved by the Mayflower Compact, an agreement establishing a democratic form of government for the colony, which is thought to have been inspired by and even modeled on Robinson's covenant for the Leiden congregation, which was also based on the concept of one-man-one-vote and the rule of the majority.

The compact is also thought to have been influenced by Robinson's last letter to Carver before the congregation's departure, which reads:

Lastly, whereas you are to become a body politic, using amongst yourselves civil government, and are not furnished with any persons of special eminency above the rest, to be chosen by you into office of government; let your wisdom and godliness appear, not only in choosing such persons as do entirely love and will promote the common good, but also in yielding unto them all due honor and obedience in their lawful administrations, not beholding in them the ordinariness of their persons, but God's ordinance for your good; not being like the foolish multitude who more honor the gay coat than either the virtuous mind of the man, or glorious ordinance of the Lord. But you know better things, and that the image of the Lord's power and authority, which the magistrate bears, is honorable, in how humble persons soever. And this duty you both may the more willingly and ought the more conscionably to perform, because you are at least for the present to have only them for your governors, as you yourselves shall choose. (Of Plymouth Plantation, Book I. ch.7)

The Mayflower Compact stipulated that each male over the age of 21 would have a voice in establishing laws and that everyone who signed the document on 11 November 1620 CE agreed to abide by it. None of the passengers were upper class, as Robinson notes in his line regarding “special eminency above the rest” and so those chosen to govern would be granted their authority by the governed, not by virtue of social status or adherence to any tradition. The rest of Robinson's letter further encourages harmony between the members of the congregation as well as with the Strangers and others they might encounter, all points which the Mayflower Compact addresses.

Conclusion

During the winter of 1620-1621 CE, half the passengers and crew of the Mayflower would die, and in the spring of 1621 CE, the colonists were still struggling until they received help from the Native Americans of the region. They were first welcomed by Samoset (also given as Somerset, l. c. 1590-1653 CE) who introduced them to Ousamequin (better known as Massasoit, l. c. 1581-1661 CE) and Tisquantum (also known as Squanto, l. c. 1585-1622 CE) who taught the colonists how to plant crops and otherwise survive in their new home. A treaty was established between the colony and the Wampanoag Confederacy led by Massasoit to look out for each other's interests which would be honored throughout Massasoit's life, but within a year conflict threatened this treaty.

Weston sent more colonists who established a settlement at Wessagussett and, poorly provisioned, began to steal from the neighboring Native Americans. In 1622 CE, the colonists at Plymouth were told that the Native Americans of the Massachusetts tribe were planning to attack Wessagussett and then take Plymouth to prevent reprisals. Captain Myles Standish (l. c. 1584-1656 CE) was sent by Bradford (by then the governor, as Carver had died in April 1621 CE) to Wessagussett to deal with the situation. Upon arriving, Standish found no evidence of any planned attack but decided on a preemptive strike and killed the Native Americans suspected of encouraging the plans against the colonies.

When Robinson heard of Standish's action, he condemned it in a letter to Bradford, noting how the “heathenish Christians” of Wessagussett had provoked the Native Americans, that there had been no need for bloodshed, and that Standish's action had set a precedent which would lead to more violence in the future:

Concerning the killing of those poor Indians, of which we heard at first by rumor, and since by more definite report, oh! How happy a thing had it been if you had converted some before you had killed any. Besides, where blood once begins to be shed, it is seldom staunched for a long time after. You will say they deserved it. I grant it; but upon what provocation from those heathenish Christians?...and indeed I am afraid lest, by this example, others should be drawn to adopt a kind of ruffling course in the world. (Of Plymouth Plantation, Book II. ch. 5)

Robinson's fears were not only justified but proved prophetic since, as more ships arrived bringing more and more colonists to North America between 1622-1636 CE, no treaties were drafted between them and the Native Americans comparable to the one forged between Plymouth and Massasoit. The “ruffling course in the world” Robinson warns of in his letter, by which he means destructive and unproductive policy and behavior, became the standard mode of operation for the colonists as Native American land was taken and settlements proliferated.

The Plymouth Colony honored their treaty, however, throughout the time of the original colonists' lives and that of Massasoit. Robinson's long-distance direction and guidance is thought to have influenced this policy and helped to maintain peaceful and productive relations which continued until King Philip's War of 1675-1678 CE. He continually encouraged and admonished the colonists, always hopeful of joining them as soon as possible, until his death in 1625 CE.

Afterwards, the members of the congregation at Leiden who had not already left for North America joined the Dutch Reformed Church, and the Leiden congregation was ended. Robinson, however, continued to be remembered and honored for his compassionate leadership and direction of those directly under his authority in the Netherlands as well as those across the sea at Plymouth, and the significance of his legacy as the spiritual mentor of the Plymouth Colony continues to be recognized in the present day.