The Puritans were English Protestant Christians, primarily active in the 16th-18th centuries CE, who claimed the Anglican Church had not distanced itself sufficiently from Catholicism and sought to 'purify' it of Catholic practices. The term was originally an insult used by Anglicans to refer to people whom they claimed were too easily offended by the liturgy of the Anglican Church and were nitpicking at details and causing trouble while justifying their efforts through proof-texting of the Bible. Puritans did not use the term to refer to themselves, primarily using 'Saints' as a self-referent.

Although initially a small sect of dissenters who drew inspiration from the writings of the religious reformer John Calvin (l. 1509-1564 CE), Puritanism became more widespread toward the end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th century CE. They objected to the use of the Book of Common Prayer, the Anglican Church hierarchy (which mirrored that of the Catholic Church), the use of incense and music in worship services, and a number of other aspects of Church liturgy and practice. Under Queen Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603 CE) they were accommodated (for the most part) while under her successor James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE) they were persecuted.

Half of the passengers aboard the Mayflower, who founded Plymouth Colony in North America in 1620 CE, were Puritan separatists – those who believed the Church could not be redeemed and true believers should separate themselves from it – who were fleeing James I's persecutions. Many of those who would colonize New England in the years following the establishment of the Plymouth Colony were also Puritans (but not separatists) who sought to leave Anglican practices and persecutions behind and found their own colonies in North America informed by their religious beliefs.

Puritanism in England continued to grow and exert considerable political power by the mid-17th century CE, finally influencing two civil wars and the establishment of the Commonwealth (1649-1660 CE) and the Protectorate (1653-1659 CE). Puritanism as a political force declined after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 CE while, in North America, it flourished through the mid-18th century CE. Puritanism influenced the governing bodies of many of the original 13 English colonies along the east coast of North America and continued this influence until shortly before the American Revolution (1775-1783 CE) but, even afterwards, continued to inform societal norms and customs, especially in New England, and continues to have an effect on the culture of the United States, to greater or lesser degrees, in the present day.

Origin & Development of Puritanism

The Protestant Reformation (1517-1648 CE) broke the unity of the Catholic Church and established Christian denominations in countries throughout Europe. One of the early Protestant reformers was the Swiss theologian Jean Cauvin (better known as John Calvin) who advocated for a literal reading of the Bible as God's word and strict adherence to the scriptures in directing one's life. King Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547 CE) followed the lead of other countries in rejecting Catholicism and establishing the Anglican Church, but he had no interest in theological matters or how his church was to be organized and so had no objections to modeling it closely on the Catholic paradigm people were used to.

This decision offended a small number of Protestants who had expected the same sort of radical break with Catholicism they had heard of in other countries, such as Germany, and they began advocating quietly for further reform. These people were labeled 'Puritans' by their fellow Anglicans for their efforts to 'purify' the Church. The term was hardly complimentary and its initial use would correspond to calling someone 'high-strung' or 'uptight' in the present day because the Anglicans saw these Puritans as needlessly objecting to aspects of worship which were generally regarded as harmless and beneficial.

It was not only aspects of worship or practice that the Puritans objected to, however, but holidays – such as Christmas – and various forms of entertainment. They objected to the popular pastime of bear-baiting (in which a dog was let loose in a pen to attack a chained bear), dog fights, cockfights, and the theater. Theaters in cities such as London were located in the same area as brothels and actors were regarded as people of loose morals and low character.

Elizabeth I & James I

Henry VIII was succeeded by his son Edward VI of England (r. 1547-1553 CE) who was far more interested in religious matters than his father had been. Edward VI reorganized the Anglican Church to distance it from Catholicism and during his reign many priests and theologians were Calvinists. He was succeeded by Mary I of England (also known as “Bloody Mary”, r. 1553-1558 CE) who reversed the reforms of Henry VIII and Edward VI to restore Catholicism. She persecuted the Protestant dissenters in what became known as the Marian Persecutions, burning many of them at the stake, and restored Catholic properties that had been confiscated by Henry VIII. Puritans who could afford to do so fled the country for the continent and were later referred to as Marian exiles.

Her policies were reversed by her successor and half-sister Elizabeth I who restored Protestantism in the form of the Anglican Church with herself as its head (just as Henry VIII and Edward VI had been). The Elizabethan Religious Settlement of 1559 CE created the distinct ecclesiastical entity of the Anglican Church and made allowances for compromises between Calvinist Puritans and others who did not share their views. The Marian exiles began returning from the continent, however, and they objected to the Settlement and its compromises because, to them, Protestant efforts in France and Germany had gone much further in distancing themselves from Catholicism and creating Bible-based churches which were self-governing (also known as Congregational) in which elected elders made policy instead of bishops.

Tensions between the crown and the Puritans grew, even while Puritans or Puritan sympathizers held important positions in the Anglican Church, and led to underground networks of Puritans who sought to radically challenge the authority of the queen and her church. This challenge finally took the form of a pamphlet war known as the Marprelate Controversy. An anonymous Puritan author who signed himself as Martin Marprelate published a number of tracts attacking the queen, the Church, and individual priests and bishops between 1588-1589 CE.

A nationwide manhunt was launched to find Marprelate, and while that was ongoing, Elizabeth had her own writers publish tracts answering Marprelate's criticisms. Marprelate was never found, but his presses were discovered and destroyed at the same time the distribution network was broken. The Marprelate Controversy resulted in the further reformation and consolidation of the Anglican Church as well as the establishment of laws treating criticism of the Church as treason against the monarchy.

When James I succeeded Elizabeth I in 1603 CE, he sought to resolve the religious conflicts and assembled the Hampton Court Conference of 1604 CE which was a meeting of Puritan theologians and Anglican bishops. James I listened to both sides of the argument and rejected Puritanism. The Puritans used the translation of the Bible known as the Geneva Bible, influenced by John Calvin's theology, as their scripture and so James I commissioned the leading scholars of the day to create a new translation, the King James Bible, which would support his theological views and those of the Anglican Church. He also authorized Church officers to work in conjunction with secular law enforcement to arrest, fine, imprison, and even execute Puritan dissenters.

Theology & Conflict

The Puritans refused to compromise their faith, believing the Bible was God's word and one should live as closely to the model of Jesus Christ and his twelve disciples as one could. To the Puritans, any aspect of religious observance or personal behavior that did not appear in the Bible, or at least could be justified by it, was not of God and should be rejected. The Anglican Church's insistence on retaining the position of bishops, using the Book of Common Prayer, allowing priests to wear vestments like Catholic priests, burning incense during worship services, and allowing music went to convince the Puritans that the Church was corrupt and under the influence of Satanic powers.

Puritans held that there was nothing more important in life than one's religious belief which dictated how one comported one's self in this world and gave one hope of salvation and eternal life in the next. Their belief in pre-determinism meant that they could not actually know if they were 'saved' as that was known only to God, but they could act in a way befitting one of the elect whom God had already chosen. They believed in what is known as Covenant Theology, a quid pro quo relationship between the individual and God in which a believer acted in accordance with God's will as given in the Bible and God rewarded the believer's efforts.

Among their most important observances was what is known as Sabbatarianism, the strict observance of the Sabbath during which God was to be one's sole focus and no work could be done nor any leisure activity pursued. The pulpit became the focal point of worship services because the sermon was considered its most important aspect in accordance with the biblical admonition “So then faith comes by hearing, and hearing by the word of God” (Romans 10:17). Young boys were brought up in their father's trade to be industrious while girls were taught to be homemakers, but literacy was encouraged for both sexes since it was believed that everyone should be able to read the Bible.

Attending the theater, at any time, was prohibited as were games of chance like dice. Alcohol was allowed but drunkenness severely frowned upon. Sex was encouraged only within marriage, and both husbands and wives were expected to be able to sexually satisfy each other. Women were considered spiritually and morally inferior to men as they were tainted by the spirit of Eve who had caused the Fall of Man in the Garden of Eden, they but were to be respected and cared for as homemakers and bearers of children.

This theological view did not in any way endear the Puritans to James I or most members of the Anglican Church. Moderate Puritans continued to serve in the Church in the early years of James I's reign, but the fundamentalists formed their own congregations and met secretly, especially the so-called separatists who believed one needed to leave the Anglican Church completely to save one's soul. These secret meetings were illegal, and when a congregation was discovered, its members were persecuted.

The Great Migration

Puritans began smuggling themselves out of England to the Netherlands where there was greater religious tolerance and a number of congregations established themselves in Amsterdam. One such congregation, in the Village of Scrooby, England, was discovered by the Anglican Archbishop Tobias Matthew (l. 1546-1628 CE) in 1607 CE, and its members were arrested and fined. The group was led by the pastor John Robinson (l. 1576-1625 CE) who afterwards resolved to go the same route others had and leave for the Netherlands. They first moved to Amsterdam but, finding dissent among the Puritan congregations too rife there, moved on to Leiden.

Although the presses and distribution network of the Marprelate tracts had been destroyed, Puritans continued to publish illegal tracts, pamphlets, and broadsides criticizing the Anglican Church. In 1618 CE, one of the leading members of the Leiden congregation, William Brewster (l. 1568-1644 CE), published such a tract and had it smuggled into England. James I ordered Brewster's arrest and this encouraged the congregation to move elsewhere.

By this time, England had tried to establish colonies in North America thrice with two failures – Roanoke Colony and Popham Colony – and one success – Jamestown Colony of Virginia. The separatists of Robinson's congregation decided to establish their own, and a number of them left for the New World aboard the Mayflower in 1620 CE. Although they lost half their number to disease and malnutrition the first winter, the survivors established the successful Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts, and word of this reached England in 1622 CE along with the pamphlet known as Mourt's Relation, written by two of the colonists, William Bradford (l. 1590-1657 CE) and Edward Winslow (l. 1595-1655 CE), describing the region in glowing terms and encouraging others to make the journey.

The success of the Plymouth Colony led to what is known as the Great Migration (or the Puritan Migration) between 1620-1640 CE during which over 20,000 English Puritans migrated to New England, settling in Massachusetts primarily. In 1630 CE, a fleet of ships carrying 700 Puritans under the leadership of John Winthrop (l. c. 1588-1649 CE) arrived and established the Massachusetts Bay Colony centered around Boston. Winthrop believed this colony would be a City on a Hill (a reference to the biblical passage of Matthew 5:14: "You are the light of the world. A city that is set upon a hill cannot be hidden") which would draw others to it and be an exemplar of true Christian faith.

Puritans in North America

The Puritans had come to North America in order to worship freely without fear of persecution, but they were not interested in the religious freedom of others. The Massachusetts Bay Colony, though not a theocracy, was informed by Puritan belief and demanded strict adherence to proper behavior (as defined by the Puritans) from its citizens. Native Americans were considered in dire need of salvation and so missionaries were sent to convert the neighboring tribes which resulted in so-called 'praying Indians' who were no longer welcomed by their people and were considered inferiors by the Puritans and so were relegated to a kind of no man's land in between the two.

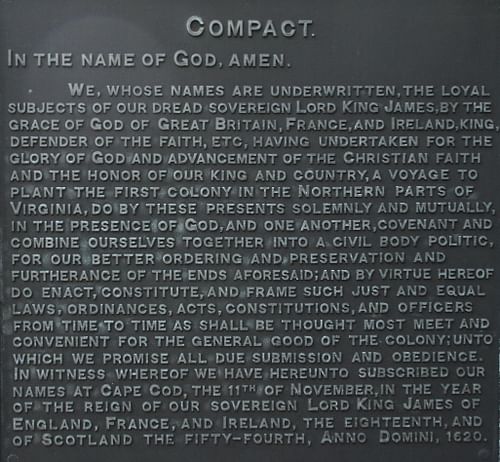

Those of other faiths were persecuted by the Puritans just as the Puritans had once been by the Anglican Church back in England. Jews, Catholics, Anglicans, and other Christian sects were considered hell-bound, but none more so than the Quakers. The Quakers inspired especially harsh persecution because they believed a spark of the divine light was present in everyone and so every person was worthy of respect. This contradicted the central Puritan belief in the 'elect' and themselves as God's chosen people. The intolerance of the Puritans and their persecution of non-Puritans led to further migrations by these groups (and also by other Puritans who were more tolerant and open-minded) to surrounding regions which became the states of Rhode Island, Connecticut, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. The original constitutions of some of these states were influenced and inspired by the Puritan separatist document, the Mayflower Compact, which established the government of the Plymouth Colony and then served as a model for others.

The Puritans influenced the development and culture of the United States in many other ways. Since the Puritans rejected Christmas, it was not celebrated in the United States until 1870 CE. Literacy was a primary value because only by reading the Bible could one know God's will and so public education was advanced. Harvard University was founded by the Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1636 CE in order to train clergy, and they also encouraged medical knowledge and practice. The strict observance of the Sabbath led to the so-called blue laws which restrict certain activities and the sale of alcohol on Sundays.

The Puritans also encouraged racism and sexism as they believed that Africans, women, and Native Americans were naturally inclined toward Satan or, in the case of women, too weak to resist the devil's temptations. The persecution of women through witch trials was not confined only to Salem, Massachusetts in the 1690s but was pursued in a number of states throughout New England. The Puritans also engaged in and profited from the slave trade, selling the Native Americans of the Pequot tribe into slavery at the conclusion of the Pequot Wars of 1636-1638 CE, importing African slaves, and selling salted cod en masse to feed the slaves of Jamestown and those in the West Indies.

Conclusion

While the Puritans who had migrated were developing North America, those in England were still trying to reform the Anglican Church and gain a political voice. Their efforts would influence the English civil wars, the establishment of the Commonwealth, the execution of Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649 CE), and the rise to power of the Puritan magistrate and general Oliver Cromwell (l. 1599-1658 CE) who established the Protectorate. When the Protectorate collapsed and the monarchy was restored in 1660 CE, the Puritans of England lost their political power and advantage.

In the colonies of North America, theological disputes between Puritan congregations, as well as the arrival of people of other faiths, gradually diluted the Puritan hold over communities by the mid-1700s CE. Their influence, however, is still apparent in United States' culture, especially through the concept known as American Exceptionalism - the claim that the United States is innately superior to other nations - which was advanced by both Bradford and Winthrop regarding their respective colonies, advanced by the Founding Fathers in the 18th century CE, and popularized in the 19th and 20th centuries CE. Since the 19th century CE, the Puritan separatists of the Plymouth Colony have been regarded as national heroes and, in the 20th, Winthrop's idealized vision of his colony as a shining "city on a hill" applied to the United States generally.