The New England Colonies were the settlements established by English religious dissenters along the coast of the north-east of North America between 1620-1640 CE. The original colonies were:

- Plymouth Colony (1620 CE)

- New Hampshire Colony (1622 CE)

- Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630 CE)

- Providence Colony (1636 CE)

- Connecticut Colony (1636 CE)

- New Haven Colony (1638 CE)

Prior to the arrival of the English colonists, the land had been inhabited by Native Americans for over 10,000 years. The tribes still occupying the region c. 1607 CE were the Abenakis, Assonet, Chappaquiddick, Mashpee, Mi'kmaq, Mohegan, Narragansett, Nantucket, Nauset, Patuxet, Penobscot, Pequot, Pocumtuck, and Pokanoket. These tribes would reduced by disease, military action, enslavement, and deportation, or assimilation by 1680 CE, and survivors moved either onto reservations or left the region to join other tribes elsewhere after the colonial victory in King Philip's War (1675-1678 CE). The colonies then occupied the vacated Native American land and flourished.

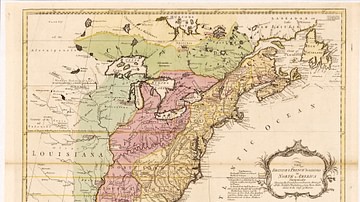

Plymouth Colony would be absorbed by Massachusetts Bay into the larger colony of Massachusetts in 1691 CE while New Haven Colony joined Connecticut in 1664 CE. Providence Colony was officially recognized as the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations in 1790 CE. Land grants given by the Province of New Hampshire, contested by their southern neighbor, the Province of New York, would eventually become Vermont in 1777 CE. The northern part of Massachusetts became the State of Maine in 1820 CE, establishing the region of modern-day New England as the states of:

- Massachusetts

- New Hampshire

- Rhode Island

- Connecticut

- Vermont

- Maine

England had first attempted colonization of the region in 1607 CE with the Popham Colony (1607-1608 CE) which failed after 14 months. The success of Plymouth Colony (1620-1691 CE) encouraged the establishment of the New Hampshire Colony and Massachusetts Bay Colony while Providence Colony, Connecticut Colony, and New Haven Colony were founded by dissenters from Massachusetts Bay. All of these settlements were established by Puritans, separatists, or others seeking freedom of religion and personal liberty for themselves while, with the exception of Providence, denying the same to others. The colonies would continue this model not only in their Native American policies but through the institution of slavery, establishing a pattern of systemic racism still evident in the policies and practices of the nation they helped establish.

Native American New England

Before the arrival of European settlers, the land was inhabited by the people who had occupied it going back at least 10,000 years. The indigenous people were semi-nomadic with seasonal settlements along the coast and more permanent villages in the interior (though there were exceptions to this model). The land was considered a gift from the Great Spirit (most often designated as Manitou), and the people had no concept of private ownership of the land, although different tribes regularly used specific areas and there were wars over resources when one tribe infringed on another's established right to a region.

The natives observed a matrilineal cultural system in which the family name and tribal status was passed down through the woman's side, and women were active in the government of the tribe, as elders especially, who chose the next sachem (chief). Native Americans subsisted on agriculture, growing beans, maize, and squash (the “three sisters”), on hunting, fishing, and foraging. By the 17th century CE, a number of these tribes had formed themselves into the Wampanoag Confederacy to protect themselves and their resources from others. The sachem of the Pokanoket tribe presided over the others who each had a lesser sachem and paid tribute to the Pokanoket.

English Colonization in North America

European colonization of the Americas began with the arrival of Christopher Columbus (l. 1451-1506 CE) in the West Indies in 1492 CE, claiming the land for Spain. Spain then expanded their claims throughout South and Central America (except for Brazil which was claimed by Portugal in 1500 CE) up through areas of lower North America. France claimed Canada and established the first settlement in what would become New England on the island of St. Croix (off the coast of Maine) in 1604 CE. Over half the settlers died the first winter, however, and the colony was abandoned. The Dutch claimed lands to the south, establishing themselves in the area of the Hudson River Valley by 1614 CE and other European nations made their own claims to other regions at this time.

England, therefore, was a latecomer to North American colonization. The first attempt, Roanoke Colony, was established in 1585 CE and had failed twice by 1590 CE. Under King James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE), a more concentrated effort was made and two companies formed for the express purpose of colonizing North America for profit: the Virginia Company and the Plymouth Company. Virginia Company was given permission to colonize the region from just above modern-day Florida to the lower Hudson Valley while the Plymouth Company was granted the area from present-day northern Maine down to the upper Hudson Valley.

In 1607 CE, The Virginia Company established the Jamestown Colony of Virginia and the Plymouth Company founded the Popham Colony in present-day Maine. Jamestown struggled in its first years, losing up to 80% of its population, but survived and was flourishing by c. 1620 CE. The Popham Colony only lasted 14 months before it was abandoned. These two colonies were both commercial ventures launched entirely for profit, but the next expedition would have a different motivation and goal.

The Anglican Church had replaced the Catholic Church under Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547 CE), substituting the monarch for the pope. By the time of the reign of James I, it was long established that criticism of the Church was treason against the king, and dissenters, such as the Puritans, were persecuted. The Puritans wanted to 'purify' the Church of its Catholic policies but still considered themselves members, while radical Puritans, known as separatists, advocated complete separation and the establishment of independent, congregational churches.

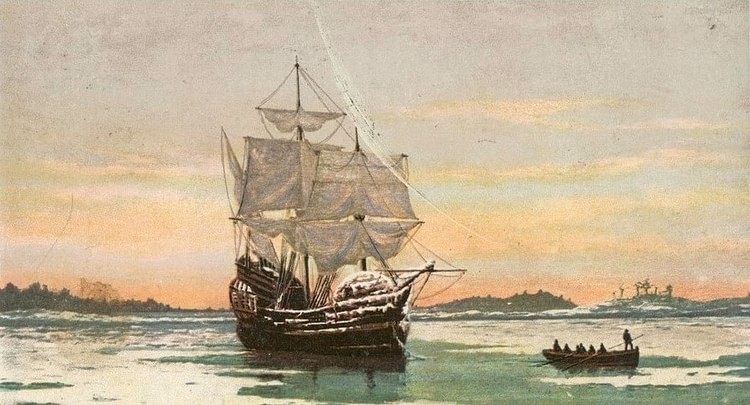

In 1620 CE, a group of separatists, joined by Anglicans, set out aboard the Mayflower to establish a colony where they could worship freely. Their destination was the Virginia Patent, but they were blown off course and landed off the coast of Massachusetts. Forced to establish a settlement outside a region under English law, they composed the Mayflower Compact to establish the colony's government; a document which would later influence the constitutions of other colonies as well as the United States Constitution.

Plymouth & Massachusetts Bay

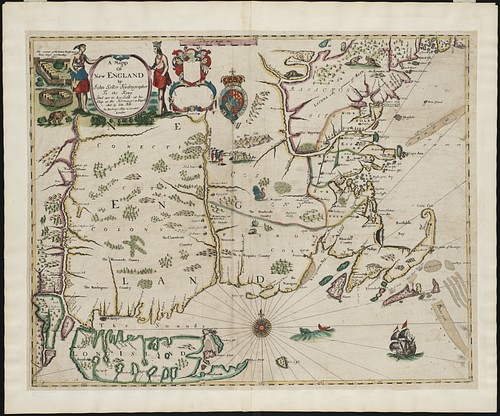

The new arrivals were acquainted with the region from the writings of Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631 CE), one of the founders of Jamestown Colony, who had mapped the area in 1614 CE and named it New England. A number of English ships had visited the region between c. 1605-1614 CE, trading with the natives and had, unwittingly, infected them with European diseases to which they had no immunity. The coastal Patuxet and Nauset tribes were most severely affected. The Mayflower passengers and crew, in fact, established their colony at the site of a former Patuxet village. Although the natives had at first welcomed the English, their trust had been betrayed when English ships began kidnapping natives to sell into slavery. By the time the Mayflower landed, the indigenous people were justifiably cautious in dealing with them.

After surviving the first winter of 1620-1621 CE, during which half of them died, the settlers of Plymouth Colony flourished only through the assistance of the sachem of the Wampanoag Confederacy Massasoit (l. c. 1581-1661 CE). Massasoit at first wanted nothing to do with the immigrants but eventually relented and sent Squanto (l. c. 1585-1622 CE) to help them. Squanto had been kidnapped by an English captain in 1614 CE, learned English, and had only recently returned. He instructed the colonists on how to survive and served as their interpreter.

Massasoit signed a treaty with the English promising mutual assistance and protection. Massasoit had lost many members of his confederacy to disease (which cost him his status with other tribes) and was at this time paying tribute to the Narragansetts. The alliance with the colonists, who needed his help to simply survive, proved beneficial to both parties. The colony was thriving by 1622 CE, and this encouraged others to make the transatlantic journey.

In 1630 CE, 700 Puritan colonists arrived under the leadership of John Winthrop (l. c. 1588-1649 CE) to settle Massachusetts Bay Colony through a charter granted by the Massachusetts Bay Company, which had replaced the Virginia Company. Winthrop believed his colony was ordained by God to be a 'city upon a hill', a shining beacon of the model Christian community, and so insisted on complete conformity to the Puritan interpretation of Christianity and resultant laws.

Providence, New Hampshire, & Connecticut

The Puritan separatist theologian Roger Williams (l. 1603-1683 CE) arrived in 1631 CE and quickly came into conflict with Winthrop and the other magistrates over religious differences. He left for Plymouth Colony, thinking he would fit in better with fellow separatists, but found the colonists there too legalistic. He also objected to both Plymouth Colony and Massachusetts Bay on the grounds that neither had paid the Native Americans for the land they had settled. Williams, who became fluent in the Native American language of Algonquian, was eventually banished from Massachusetts Bay and lived with Massasoit at his village of Sowams (modern-day Warren, Rhode Island) in 1636 CE. He negotiated with Massasoit and the sachems of the Narragansett tribe, Canonicus (l. c. 1565-1647 CE) and Miantonomoh (l. c. 1600-1643 CE) for the land on which he established the Providence Colony, paying them their asking price.

Williams' banishment was followed by others. In 1638 CE, the religious dissident Anne Hutchinson (l. 1591-1643 CE) was expelled from the Bay Colony, and Williams invited her and her followers to join his. She instead founded the colony of Portsmouth with her brother-in-law, the Puritan minister John Wheelwright (l. c. 1592-1679 CE). Wheelwright left shortly afterwards to establish the colony of Exeter in New Hampshire in 1638 CE while other Hutchinson followers such as William Coddington (l. c. 1601-1678 CE) founded Newport, Rhode Island.

New Hampshire was first established as a commercial venture in 1622 CE under a patent issued to two merchants, Captain John Mason (l. 1586-1635 CE) and Sir Ferdinando Gorges (l. c. 1565-1647 CE) neither of whom ever set foot on the land. Wheelwright tried to buy some land for his settlement from their representatives but could find none and so negotiated a sale with the natives of the region. Wheelwright's colony attracted other dissenters from Massachusetts Bay who settled the nearby areas. Lacking a legal charter, Wheelwright could not form a colonial government and so negotiated an agreement with Massachusetts Bay under which the Bay Colony would govern New Hampshire but the New Hampshire Colony was free to live and worship as they wished.

Connecticut was settled at about the same time and, again, by religious dissidents from Massachusetts Bay Colony. Connecticut Colony was founded in 1636 CE by John Haynes (l. 1594-1653 CE) and Thomas Hooker (l. 1586-1647 CE) who were among Anne Hutchinson's supporters. Haynes and Hooker contributed to the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut, considered by many scholars as the first written constitution. Other colonies, later absorbed into Connecticut, were also established both before and after the Pequot War.

Pequot War & Further Settlement

The Massachusetts Bay Colony justified the Pequot War (1636-1638 CE) by claiming that the Pequots had murdered a merchant from their settlement. The Pequots defended themselves, noting that the man in question was a notorious troublemaker who had kidnapped some of their people. The head of the Salem militia, John Endicott (l. c. 1600-1665 CE), destroyed Pequot villages and killed some of the natives, and the Pequots struck back. Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay then joined militias to mount a full-scale attack on the Pequot fortification at present-day Mystic, Connecticut in May of 1637 CE.

Roger Williams kept Providence Colony out of the conflict but encouraged the Narragansett to side with the colonists against the Pequot and also provided the militia with the plan of attack. The Mystic Massacre resulted in the deaths of over 700 Pequot, mostly women and children, and the war ended with a colonial victory. The surviving Pequot were sold into slavery either on local plantations or in the West Indies. Their land was now open for colonization, and the areas which were not then claimed by the Narragansett were settled by the English.

New Haven Colony was established in 1638 CE by English intellectuals, theologians, and merchants who had no charter, no experience in agriculture, and no support from other colonies in trying to fend off Dutch merchants who were encroaching on the areas they hoped to exploit for profit and Native Americans who objected to their land theft. They appealed to Massachusetts Bay and were accepted into the New England Confederation in 1643 CE along with Connecticut and Plymouth.

Providence Colony was excluded from the Confederation as it was considered a haven for reprobates and troublemakers (just as the earlier Merrymount Colony had been) who refused to conform to the vision of the majority. Providence, which thus far had operated without a charter, secured one in 1644 CE and incorporated the colonies of Newport, Portsmouth, and Warwick as a single colony under the leadership of Roger Williams. New Haven Colony, which continually failed in almost every business venture and never secured a charter, finally joined with the larger Connecticut Colony in 1664 CE. New Hampshire was able to break away from Massachusetts Bay in 1679 CE when they received a charter from King Charles II of England (r. 1649-1651 CE) and were legally allowed to elect their own colonial president and form a government.

Slavery & Expulsion of Native Americans

All of the colonies benefited from the institution of chattel slavery, beginning with Massachusetts Bay which enslaved the Pequots after the war. In 1641 CE, Massachusetts Bay passed its law known as the Body of Liberties, which included the provision that no human being would be enslaved except for those legally taken captive in war or those already enslaved by others and sold to citizens of the colony. Slavery was understood as approved of by God according to the Bible, which sanctions it in both the Old and New Testaments, and this accorded with Massachusetts Bay's vision.

Roger Williams was an abolitionist who outlawed slavery in Providence Colony but never enforced the law. The Rhode Island colonies, along with Massachusetts Bay, would become New England's centers for the Triangular Slave Trade between North America, Europe, and West Africa. Connecticut also enslaved Pequots and other natives, as well as importing African slaves, until 1774 CE. New Hampshire participated the least in the slave trade and slave ownership, but the upper class kept slaves until, like the others, the mid-18th and 19th centuries CE.

As the colonies became more affluent, they attracted still others from England and elsewhere, and more land was taken, usually without any payment, from the Native Americans. The Native American culture differed considerably from the English in that women were considered equal, land could not be owned, and agreements were considered binding. The English treated their women as non-citizens (they could not vote or own land), fenced in their land, and honored agreements only as long as they were of benefit. Cultural misunderstandings, including those concerning religion, inevitably led to a series of conflicts. After a string of broken treaties and near-constant abuse by the colonists, Massasoit's son, Metacom (known to the English as King Philip, l. 1638-1676 CE), united the region's tribes under the Wampanoag Confederacy and launched King Philip's War. Metacom was killed in 1676 CE, and the colonists were victorious. Afterwards, the Native Americans were moved onto reservations or left the area, and the colonies took over their lands.

Conclusion

The colonies were absorbed into a single group under the Dominion of New England in 1686 CE under James II of England (r. 1633-1688 CE) who was concerned with their growing independence and economic power. The Dominion ended with the Glorious Revolution of 1688 CE when James II was deposed, and the colonies were then allowed the right to self-government while still subject to the English monarchy. While they continued to cooperate with each other in financial matters, there were disputes over land rights and religious views. The divisions among the Puritan colonies, including the general disdain for Providence and its policy of religious tolerance, eventually caused citizens to lose their allegiance to the Puritan vision and adopt a less rigid interpretation of the Bible and the Christian path, but each still retained the belief in the value of freedom which had brought the first settlers from England.

Each of the New England Colonies contributed to the earliest efforts to win independence from Great Britain while ignoring their own policies and practices which deprived Native Americans of their land, destroyed their culture, and enslaved both those who had initially helped them survive in the New World and others kidnapped from Africa, who were neither captives taken in war nor legally purchased to be sold to them. This us-and-them mentality, which set different standards and laws for white Europeans and non-whites, would inform the policies of the new nation of the United States after the Revolutionary War and continues to in the modern era.