Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685) was the king of Scotland (1649-1685) before the Restoration in 1660 also made him king of England and Ireland. Charles was a charming and easygoing monarch who took a keen interest in sports, science, and the arts. From the acquisition of New York to the Great Fire of London, his reign was certainly eventful.

Charles returned the monarchy triumphantly to the apex of British politics and society with a magnificent coronation bedecked in the new British Crown Jewels. There were wars with the Netherlands, alliances with France, divisions at home over religion, and significant expansions overseas, particularly in India and North America. He died in 1685 and was, since he had no heir, succeeded by his younger brother, who became James II of England (r. 1685-1688).

Early Life

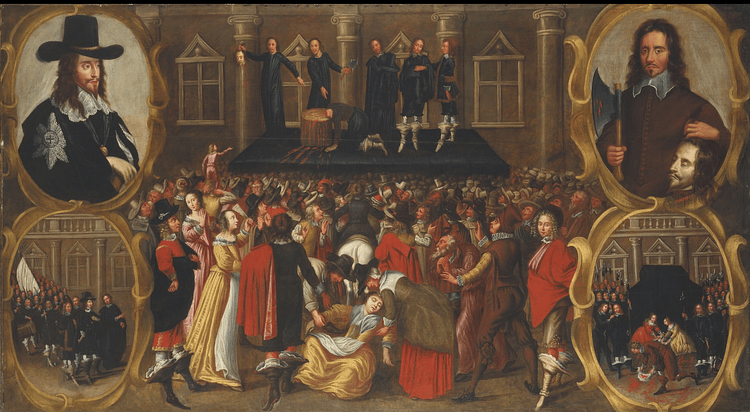

When Elizabeth I of England died in 1603 without an heir, James VI of Scotland (r. 1567-1625) was invited to also become the king of England as James I of England (r. 1603-1625). James was the first of the Stuart kings, and he was succeeded by his son Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649). Charles' battles with Parliament over religion, finances, and the power of the monarchy led to the English Civil Wars (1642-1651) and his ultimate execution on 30 January 1649.

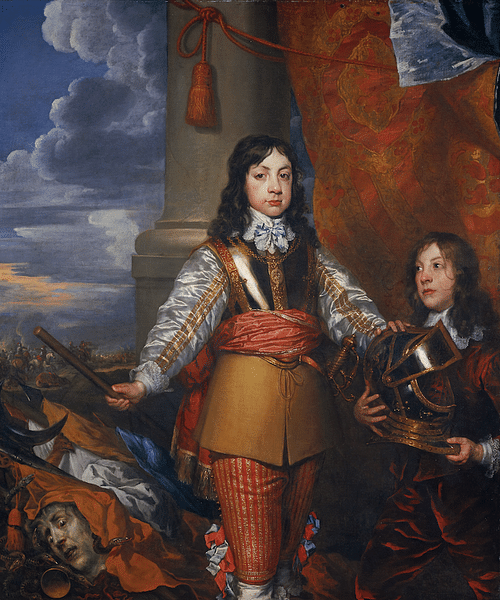

Charles I's eldest son, also called Charles, was born on 29 May 1630 in St. James' Palace, London. His mother was Queen Henrietta Maria (1609-1669), the young sister of Louis XIII of France (1610-1643). Charles spent most of his childhood at Richmond House, where he most enjoyed horse riding. After his father lost the Battle of Naseby in 1645, Charles was shipped off to the safety of France along with his mother. He "grew up tall, swarthy, and saturnine" (Cannon, 293), reaching an impressive height of 1.88 metres (6 ft 2 in). Charles seems to have been the very opposite of his rather straight-faced father. The younger Charles was charming, witty, and easy-going, and his passion for romantic encounters began with Lucy Walter (d. 1658), who bore him the first of many illegitimate children, James Scott who became the Duke of Monmouth (b. 1649).

The Anglo-Scottish War

While the monarchy was abolished in England after Charles I's execution, Scotland was permitted to choose its own way. Charles' eldest son was made the king of Scotland as Charles II in February 1649 (formally crowned on New Year's Day 1651 at Scone). Pro-Royalists rallied around Charles as their figurehead, and so began the Third English Civil War or Anglo-Scottish War (1650-1651). The Scots had switched sides since they now considered Charles their best means of preserving the independence of the Presbyterian Church in Scotland and promoting it in England, something the Puritan-dominated Parliament certainly would not do. As it happened, Charles himself had no interest whatsoever in Presbyterianism, which he described as "a religion not fit for gentlemen" (Cavendish, 324).

In 1650, Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) led Parliament's New Model Army into Scotland to persuade by force that any hope of restoring the monarchy south of the border was futile. The two armies clashed at the Battle of Dunbar in September 1650. Cromwell won yet another crushing victory. The remainder of the Scottish and English Royalist forces met for one last clash with Cromwell at the Battle of Worcester in September 1651. Again, the Parliamentarians won, and so ended the English Civil Wars. Charles was obliged to flee to France, but getting away from the battlefield at Worcester was no easy matter. The Scottish king had to first hide in an oak tree for a day near Boscobel House in Shropshire before he could, disguised as a humble servant, escape to the coast and then abroad. This escapade is the origin of the common pub name in England: The Royal Oak. Almost penniless, the king without a throne relocated to the Netherlands.

The Stuart Restoration

Oliver Cromwell was made Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland in December 1653, and so he was head of the military state known as the 'Commonwealth' Republic. Cromwell's authoritarian rule and imposition of Puritanism made many wish for the moderation and tradition of the old monarchy. When Cromwell died in 1658, his republic died with him. Cromwell had chosen for his successor his son Richard Cromwell, but he did not enjoy universal support. Following a march on London in 1660 and with the support of a Scottish army led by General George Monck (1608-1670), the monarchy was restored with Parliament's consent on 8 May. There was remarkably little political fuss, helped by Charles' promise of a free Parliament and religious toleration as expressed in the Treaty of Breda of 4 April. On 29 May, his 30th birthday, Charles was escorted to London, where he met cheering crowds and streets decorated with tapestries and flowers. Trumpets blared, and church bells rang. The monarchy was back. Parliament declared 29 May a public holiday, which thereafter became known as Oak Apple Day in reference to Charles' flight after the civil war.

In 1660, all of Cromwell's Acts of Parliament were cancelled, and Parliament's New Model Army was disbanded. In the same year, Charles I was declared a martyr by Parliament and made a saint by the Anglican Church. Puritan Cromwell received an entirely different treatment. The vindictive king had Cromwell's remains exhumed from Westminster Abbey in 1661 to receive treatment as if executed as a traitor, that is the corpse was hanged and beheaded, and the remains were put on public display. There were a few executions of living men, but, generally, Charles was willing to forgive and forget the sins of the fathers.

There were still, nevertheless, many open wounds within and without the Anglican Church and no sign of reconciliation between the opposing sides of moderate Protestants, various Puritan groups, and the Catholics. Charles favoured a lenient approach to Catholicism, but Parliament, on which he depended for finances, took the opposite view. As so many times since the English Reformation, stories of Catholic and 'Popish' plots abounded, notably one in 1678 propounded by the fantasist Titus Oates (1649-1705), which he said planned to assassinate the king. Evidence was slim for these conspiracy theories, but a wave of persecution of Catholics in one form or another did follow as a result. There was one real regicidal conspiracy, the 1683 Rye House Plot, but it came to nothing. The debate over religion would simmer along right through Charles' reign and boil over in that of his successor.

Coronation & Regalia

After the Civil War, the British Crown Jewels were broken up and sold off, but Charles II's coronation in Westminster Abbey on 23 April 1661 would have been a drab affair without some glittering baubles. Accordingly, an entirely new set of regalia was created, although some of the old gemstones were recovered and used in the new pieces. The gold St. Edward's Crown was bestowed at the actual moment of coronation and has been so used in ceremonies ever since. The Sovereign's Sceptre (aka King's Sceptre) has also become a staple part of the coronation, although today it has the added sparkle of the 530-carat Cullinan diamond. The Sovereign's Orb, symbolic of the Christian monarch's domination of the secular world, was made for Charles and is a hollow gold sphere set with pearls, precious stones, and a large amethyst beneath the cross. Every British monarch since has held the orb in their left hand during their coronation. The new jewels nearly went the way of their predecessors. A villain called 'Colonel' Thomas Blood disguised himself as a priest and tried to steal the regalia from the Tower of London in 1671. Upon hearing of the plot, Charles, impressed with his audacity, pardoned Blood in an example of the king's sympathy with audacious schemes whether they be scientific or criminal.

Building an Empire

On 21 May 1662, Charles married Catherine of Braganza (1638-1705) who was the daughter of King John IV of Portugal (r. 1640-1656). The couple had three children, but all died in infancy. Charles had many mistresses. With these women, who included a duchess, an actress, a prostitute, and a spy, the king had 16 illegitimate children. Not for nothing was Charles nicknamed after his favourite stallion in the royal stud: "Old Rowley." Following their recent independence from Spain, the Portuguese were keen to forge an alliance with England. As part of her impressive dowry, Catherine brought a huge sum of cash and gave England control of Tangiers and Bombay, formerly possessions of the Portuguese Empire.

There were some significant developments, too, across the Atlantic. On 24 March 1663, Charles granted the lands of 'Carolina' in North America to eight noblemen. The colony's constitution was written by the philosopher John Locke (1632-1704). A royal charter was granted to the Rhode Island colony on 8 July 1663. In 1665, British privateers took over from the Netherlands the port of New Amsterdam on the east coast of America, then a major hub of the fur trade. It was renamed New York when it was officially ceded by the Dutch in the 1667 Treaty of Breda. The name was in honour of the king's brother James, Duke of York, while the quarter still known as Queens was named in honour of Queen Catherine. In exchange for New Amsterdam, the British gave the Netherlands Suriname in South America. In 1681, the king granted the Quaker entrepreneur William Penn the territory of Pennsylvania in return for Penn's father cancelling the king's debt to him. All of these actions cemented Britain's control of the eastern seaboard of North America.

Back in Europe, competition for control of global trade brought a trio of wars with the Netherlands. After a bright start, things did not go well, and the Royal Navy suffered a humiliating defeat at Medway in June 1666. In 1670, Charles signed the Treaty of Dover with Louis XIV of France, which forged an alliance against the Netherlands. A secret clause of this treaty promised that, in return for cash, Charles would promote Catholicism in England, using French military support if necessary. Whether the king ever intended to keep this promise is debatable, certainly, it never became a reality, but the regular cash payments frequently came in handy and allowed the king to avoid calling Parliament more than absolutely necessary. His agreements with Louis were repeated in 1678 and 1681. There were some other consequences to the deals besides Charles' purse gaining weight. In 1672, Charles was obliged to give military assistance for Louis XIV's attack on the Netherlands, but a disappointing naval draw off Southwold in June was followed by failures on land so that the war was abandoned by 1674.

Disasters & Achievements

Back in England in the 1660s, Charles, the 'Merry Monarch', was notorious for living it up in his high-spending court and playing all manner of sports (he rode winners at Newmarket horse races and celebrated his Scottish coronation with a round of golf). He was also fond of strolling through his magnificent gardens pursued by his noisy spaniels. While the king might have been able to elude reality on his aptly named yacht The Royal Escape, there were some notable disasters for everybody else. There was another devastating wave of the Black Death plague in the unusually hot summer of 1665. In 1666, there was the Great Fire of London. This terrible blaze began in a baker's shop in Pudding Lane, not far from London Bridge on 2 September. It quickly spread through the narrow streets to engulf a huge swathe of London, then mostly composed of wooden buildings. The king personally supervised some of the firefighting activities, which went on for four days. Saint Paul's Cathedral was one of the architectural casualties; the intense heat from the fire melted the lead of its roof and sent it in a molten stream through the nearby streets. Miraculously, fewer than ten people died in the inferno, which destroyed 87 churches and 13,000 other buildings. It was hoped that a rebuilding programme funded by a tax on coal imports might rid London of many of its narrow streets, but landlords were loath to reduce their opportunities for rents, and so only a limited part of the programme came to fruition.

Amongst the devastation, the enlightenment of literature at least burned brightly. Charles' reign saw the publication of the immensely popular Christian allegory Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan (d. 1688) and the epic poem Paradise Lost by John Milton (1608-1674). Theatre, especially comedy plays, was another radiant part of a blossoming artistic scene that sprang anew after the closures imposed by the Puritans during Cromwell's reign. Such was the quantity of new works, the phrase 'Restoration theatre' was coined. The king founded the noted Royal Hospital in Chelsea for retired soldiers; its building was designed by one of the great architects, Sir Christopher Wren (1632-1723). Wren's finest achievement was the new St Paul's, which rose from the ashes of the cathedral destroyed in the Great Fire.

This period also saw the foundation of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich (1675), reflecting the king's keen interest in science and gadgets – he had his own personal laboratory in Whitehall Palace. In April 1662, he had given a royal charter to the research body that became known as the Royal Society, of which Sir Isaac Newton (1642 to c. 1627) was a prominent member.

Death & Legacy

Charles died four days after suffering a stroke in London's Whitehall Palace at the age of 54 on 6 February 1685. He was buried in Westminster Abbey. Without a legitimate heir and despite the Duke of Monmouth's attempt to take the throne by force in July 1685, he was succeeded by his younger brother James.

James II of England (also James VII of Scotland) was known as a prominent advocate of Catholicism, and many, who became known as the 'Whigs', had wanted him excluded from the succession during his brother's reign. Indeed, Parliament formally removed James from the succession in 1679, but Charles had him reinstated. The kingdom was divided, there were arguments over who should be monarch if not James, and the 'Tory' MPs were happy enough to keep the Stuart royal line going along its natural path. As it turned out, when James finally got his chance, he reigned for only three years before his pro-Catholic policies provoked the Glorious Revolution of November 1688 when he was deposed. The next king was a Protestant one, William of Orange, who became William III of England (r. 1689-1702). He reigned equally with his queen, Mary II of England (1689-1694) who was the daughter of James II. The Stuarts thus continued to rule Britain until 1714, when they were succeeded by the House of Hanover.