Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) was an accomplished cavalry commander, then head of Parliament's New Model Army, and finally Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland. The latter title was awarded to Cromwell for life after the bloody conclusion of the English Civil Wars (1642-1651) and the execution of King Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649).

Cromwell was a Puritan and a radical whose long string of victories on the battlefield across the British Isles led him to believe he had been charged by God to rid the people of a wicked king. Cromwell remains a divisive figure, seen variously as a political visionary, military genius, religious fanatic, callous invader, and regicidal despot. Whatever he may have been, by the time his reign as Lord Protector ended with his death in 1658, England's political, religious, and military landscapes had all changed forever.

Early Life

Oliver Cromwell was born on 25 April 1599, his father was Robert Cromwell, a modest country gentleman, and his mother was Elizabeth Steward. Oliver spent his childhood in Huntingdon before attending Cambridge University for one year. Cromwell married Elizabeth Bourchier on 22 August 1620, and they went on to have seven children, the most famous being the eldest, Richard (b. 1626). In 1628, he represented a Cambridgeshire borough as a Member of Parliament. In the 1630s, Cromwell, earning his living as a yeoman farmer near St. Ives in East Anglia, underwent a religious conversion. Thereafter, it was rare that he spoke or wrote without liberally seasoning his often fervent speech with the religious language typical of a zealous Independent or Congregationalist, that is one who called for more inclusion in the Church and greater freedom for 'independent' congregations that assembled according to the individual believers' consciences.

As a committed Puritan, Cromwell lived plainly, dressed soberly, and enjoyed modest and traditional pursuits like hunting and hawking. In the mid-1630s, his fortunes rose following the death of an uncle and the inheritance of an estate near Ely, Cambridgeshire. In 1640, Cromwell was back in Parliament as MP for Cambridge.

The historian R. Starkey gives the following summary of Cromwell's character:

He was a big, bony, practical, rather awkward man – hands-on, sporty, unscholarly despite his Cambridge days, but with the gift of the gab and a knack for popular leadership. Fearless, with no respect for persons however grand or institutions however venerable, Cromwell was a man waiting for God to reveal Himself to him in actions.

(342)

Cavalry Commander

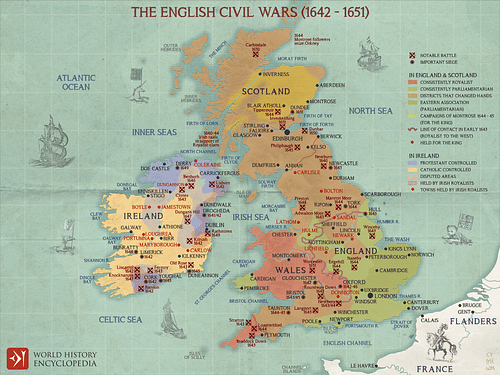

In July 1642, England finally descended into civil war after years of political wrangling and empty promises between Parliament and King Charles I. The two sides had disagreed over money, religion, and how political power should be distributed. The opposing sides became known as the 'Roundheads' (Parliamentarians) and 'Cavaliers' (Royalists). During the early years of war, most Parliamentarians merely wanted to force the king to see the error of his ways and have some of his powers curbed by Parliament. It was not, as yet, an objective to abolish the monarchy.

From 1642, Cromwell was a captain in the cavalry of Parliament's Eastern Association army led by Edward Montagu, Earl of Manchester (1602-1671). He commanded his own troop, which he expanded thanks to the wealth of his Ely estates.

Cromwell rose to become a cavalry commander thanks to his success as a leader and the victories he won on the battlefield. Cromwell was a strict disciplinarian, and he believed he was God's instrument against a wicked king. As the historian T. Hunt notes:

His biblical literalism was joined to an awesomely fiery temper and out it spewed in his letters and speeches. He warned his fellow Roundhead commanders, 'I had rather have a plain russet-coated captain who knows what he fights for, and loves what he knows, than that which you call a gentleman and is nothing else.'.

(xiii).

Cromwell's personal heavy cavalry regiment, unusually strong with 14 troops, was known as the 'Ironsides' after the nickname given to Cromwell by the Royalist cavalry commander Prince Rupert, Count Palatine of the Rhine and Duke of Bavaria (1619-1682).

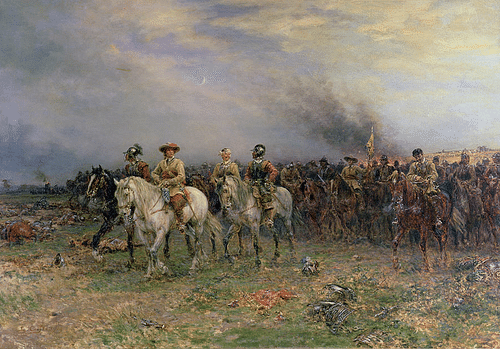

Marston Moor to Preston

The result of the first major engagement of the Civil War at the battle of Edgehill in Warwickshire in October 1642 was indecisive, a lack of progress that would become typical of the long-drawn-out conflict. The First Battle of Newbury in Berkshire in September 1643 ended in another draw. Parliament had the bulk of resources and control of both the capital and the Royal Navy, so the lack of progress was disappointing, to say the least. The Roundheads did win the Battle of Marston Moor near York in July 1644, the largest battle of the entire conflict and one which first saw the appearance of Oliver Cromwell. On Marston Moor, a wing of the Parliamentary cavalry was led with aplomb by Cromwell and Sir David Leslie (c. 1600-1682), although Cromwell was injured in the neck and was obliged to leave the field of action for some time. Leslie and Cromwell had routed the opposition cavalry and turned on the infantry with great and terrible effect. Commanding cavalry and keeping mounted troops in formation after one attack to launch a second in another part of the battlefield was extremely difficult to achieve in practice. It was a tactic Cromwell would repeat again and again as the war progressed.

Despite the loss at Marston Moor, King Charles fought on, and it was the indecisive Second Battle of Newbury in October 1644 that persuaded Parliament they had to ring the changes in their armies if they were to achieve final victory. At Newbury, the Royalists had been outnumbered 2:1, but a lack of coordination between Parliament's commanders brought about the necessity for change. Even Cromwell had not enjoyed his customary success at Newbury. Parliament conducted an official enquiry into the debacle which should have won the war. The Earl of Manchester came in for criticism for not being very proactive in the battle, although he accused Cromwell of disloyalty in a very public spat between the two men.

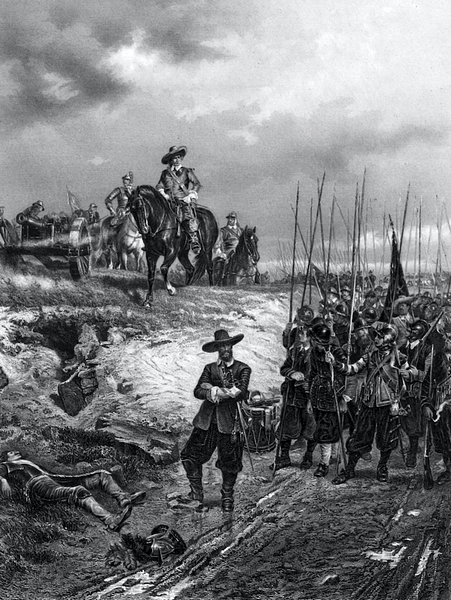

In Parliament, Cromwell called for a more professional army and general approach to the war in December 1644. February 1645 saw the formation of the New Model Army, funded by taxes. It was a professional army in terms of its paid personnel, training, and a defined hierarchy of leadership. Troops were issued with Bibles and printed catechisms, which outlined the cause they were fighting for. All regiments had chaplains, and there were regular sermons and prayer meetings.

In April, Parliament passed the Self-Denying Ordinance, a motion forbidding any of its members from being a military commander. The effect was to remove commanders who were politically powerful but had no military competence. Manchester was one of the casualties of this policy. Overall command of the Model Army was given to a talented and experienced campaigner, Sir Thomas Fairfax (1612-1671). His second-in-command was appointed at his own insistence regardless of the Ordinance: Cromwell. With a standing army that could take the field wherever their commanders thought best and for however long it took to gain victory, the Parliamentarians had taken one of the most important decisions of the entire war.

The first test of the New Model Army was at the Battle of Naseby, Northamptonshire in June 1645. King Charles led his army in person, but the Model Army was superior in numbers and tactics with Cromwell's cavalry once again distinguishing themselves – the commander even lost his helmet in the fray. The Royalist infantry was destroyed, thousands of prisoners were taken, and perhaps most significantly of all, Charles' personal writing cabinet was taken. The king's correspondence proved without a doubt that he had no intention of negotiating an end to the war and that he was willing to strike an agreement with Irish rebels to have his army bolstered by Catholic troops. The king himself, meanwhile, escaped to fight another day. He first fled to the north of England, and then, after being handed over to Parliament by a Scottish army, he escaped his imprisonment to establish himself on the Isle of Wight. From there, he plotted the extension of the war.

The Republic

The Battle of Preston in Lancashire (17-20 August 1648) was another great Parliamentary victory. Cromwell led the Model Army against a larger Scottish army that had hoped the restoration of Charles would promote the Presbyterian Church in Scotland and England. Cromwell went on to recapture Berwick, Carlisle, and Pontefract, securing the north of England for Parliament. For many, Charles could not now be tolerated. He was a 'man of blood', a king who had waged war against his own people.

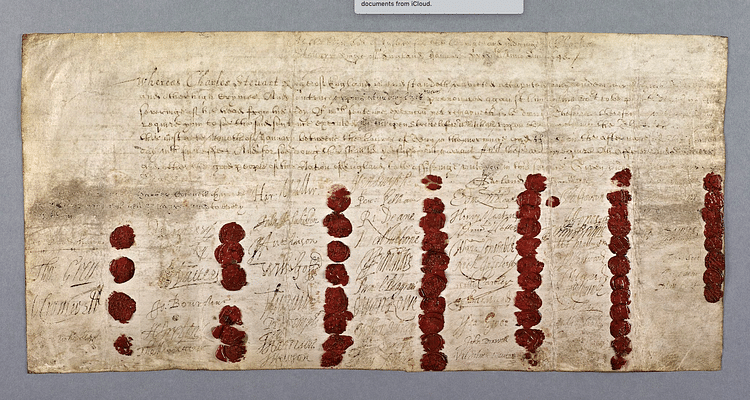

The creation of the 'Rump Parliament' in December 1648 saw the number of MPs reduced to just 150 more compliant members. It was, in effect, a military coup as the all-powerful New Model Army purged the House of Commons of anyone who stood against it. King Charles was tried, found guilty, and executed on 30 January 1649. Cromwell's signature was third on the death warrant. In March, Parliament formally abolished the monarchy as an institution and the House of Lords with it. The Anglican Church was reformed and the British Crown Jewels sold off. England became a Republic, known as the Commonwealth of England.

Crucially, the monarchy was not abolished in Scotland, where, in February 1649, the late King Charles' eldest son automatically became Charles II of Scotland. The Scots supported Charles as a means to defend the Presbyterian Church in Scotland, and one of their conditions for military support was that the king promised to promote that church in England should he be made king there. There were, too, diehards in England who considered Charles as their rightful ruler, even if he were in exile in France. The civil wars were not over yet. Round three began, and it was the threat from Scotland that mobilised the Model Army once more.

Ireland & Scotland

Before Cromwell could deal with the Scots, he first led an army of 12,000 men to Ireland in 1650 to ruthlessly crush a Royalist rebellion there. The Model Army won crushing victories at Wexford and Drogheda. The accusations of extreme violence to captured soldiers and hundreds of unnecessary civilian deaths in the Irish campaign tainted Cromwell's reputation thereafter.

The Scots, meanwhile, continued to rally around Charles II, and they now had a sizeable army in Edinburgh under the command of David Leslie (Cromwell's old cavalry colleague on Marston Moor). Parliament decided to send the Model Army into Scotland and remove this threat once and for all. Fairfax did not approve of such a measure and resigned his commission. Cromwell took over as commander-in-chief and led the army in person. He twice tried to take Edinburgh in July-August 1650. Falling back to his base at Dunbar, he was pursued by Leslie who thought he could crush the English while trapped against the coast. As it turned out, Leslie's choice of terrain was poor and Cromwell turned what looked like a probable disaster into a glorious victory, routing the Scottish cavalry and infantry at the Battle of Dunbar in 1650. Cromwell next took Edinburgh Castle on Christmas Eve.

Still the Scots persisted and formally crowned Charles II at Scone on New Year's Day 1651. In a last desperate throw of the dice, Charles sent Leslie with the remnants of his army to invade England, but local Royalist support was not forthcoming, and, yet again, Cromwell was there to defeat him at Worcester on 3 September 1651. The Kirk in Scotland was dissolved, and, instead, representatives (as with Ireland) were sent to the Westminster Parliament. Cromwell had done what no other English king had ever managed. He had unified Britain into a single political entity. The civil wars were over.

Lord Protector

There remained serious cracks in this enforced unity of Britain. Parliament and the army were still at odds, and few could agree on how to proceed without a monarchy. On 20 April 1653, Cromwell entered Parliament and informed its members they were not fit to rule, famously declaring, "You have sat here too long for the good you do. In the name of God, go!" (Phillips, 150). The 'Rump Parliament' was closed down. On 16 December 1653, Cromwell was appointed the Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland by a new, much smaller Parliament, known disparagingly as the 'Barebones Parliament' (a play on words of one of its members), which then voted to dissolve itself and leave the executive authority in the hands of Cromwell and the Council of State. Rather ironically, Lord Protector was the old title for a monarch's regent, and it meant Cromwell was the military dictator of Britain, a king in all but name.

The Republic was divided into military districts, each led by a major-general, but Cromwell's particular brand of militarism and Puritanism was far from popular. Although there was greater religious toleration (Catholics were excluded from this), there were some unwanted radical developments. The celebrations of Christmas and Easter were abolished, and certain sports were banned on Sundays. There were controls on clothing, swearing, and other areas of life, which people were not at all used to being interfered with. There were still, too, those who sympathised with a system of the monarchy, such as the secret society the Sealed Knot and radical groups like the Levellers who sought to equalize wealth and extend suffrage. Occasionally, there were minor uprisings like the one led by Major-General Desborough in Devon in March 1655, but these were ruthlessly crushed.

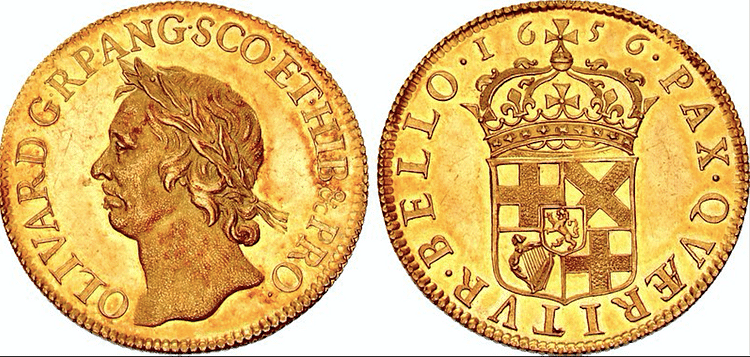

Parliament wanted to make Cromwell king, not to gain his favour but because they could then better control him as a constitutional monarch. Anything was better than a dictator who made up the rules as he went along. The army was adamant they would not support a new king when they had spent so long ridding themselves of the old one. Cromwell himself did not accept the title either, but he did accept to be inaugurated for a second time as Lord Protector, this time with much pomp and ceremony in Westminster Hall. This came about after an assassination plot by a Leveller was discovered in January 1657, which raised the question of who would replace Cromwell after his death. The solution was to allow the Lord Protector to nominate his successor. It seemed in many respects, that day on 26 June 1657, like so many coronations that had gone before. Cromwell was seated on the traditional Coronation Chair and given an imperial purple robe, a sword and a sceptre. The gathered dignitaries shouted, "God Save the Lord Protector." The only thing missing was a crown, but this was not omitted on either Cromwell's coins or his Great Seal.

Foreign Policy

Foreign rulers looked on at the bloody events in England and the execution of a king with horror, but none offered any practical assistance to the royalist cause after Charles' death. The disharmony in government in England through the 1650s was in no way helped by wars with the Dutch and then Spanish, although Cromwell earned the respect, if not the endorsement, of other European powers for his strong rule and the power he wielded at the head of his formidable army.

Cromwell's policy of attacking the Spanish Empire in the Caribbean in 1654-1655 was not a success, but it did at least secure Jamaica. In 1658, infantry of Cromwell's Model Army joined with the French to attack the Spanish Netherlands, and so Dunkirk was acquired at the Battle of the Dunes on 14 June 1658. This must have been a doubly-satisfying result since Charles II's younger brother, James, led a Royalist force on the Spanish side. The Lord Protector's foreign policy brought mixed results at best, but his investment in the Royal Navy would be fundamental in making Britain one of the great world powers in the next century.

Death

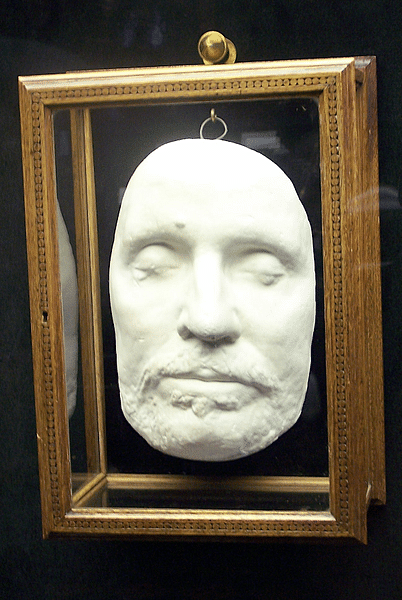

At the pinnacle of his powers, higher than any monarch before him, Cromwell suffered from what even he could not control: ill-health. He died of pneumonia at Whitehall Palace on 3 September 1658 (the date of his victories at Dunbar and Worcester). Cromwell received a state funeral worthy of a king, indeed, by the Lord Protector's body in Westminster Abbey was an imperial crown while in his lifeless hands were his orb and sceptre.

The army had fiercely resisted any move by Cromwell to nominate an heir and make his office hereditary, but on his deathbed, he did just that. His son Richard was chosen as Lord Protector, but he did not have the personality to sit astride the two snarling tigers of state: the Army and Parliament. In May 1659, a number of lower officers broke ranks and sided with Parliament in voting for the abolition of the Protectorate. The army could do little because it was divided and without a single authoritarian figure who could pull the factions together. The next year, faced with a stark choice between a monarchy or another civil war, Parliament voted for the Restoration of the Monarchy under pressure from General George Monck (1608-1670). Charles returned in May 1660 to become Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685), and he was invited to rule alongside the House of Lords and the House of Commons. All of Oliver Cromwell's Acts of Parliament were cancelled; the Republic was dead. To make doubly sure, Cromwell's remains were exhumed from Westminster Abbey in 1661 to receive treatment as if executed as a traitor, that is the corpse was hanged and beheaded, and the remains were put on public display as a warning for those who would be king without a crown.