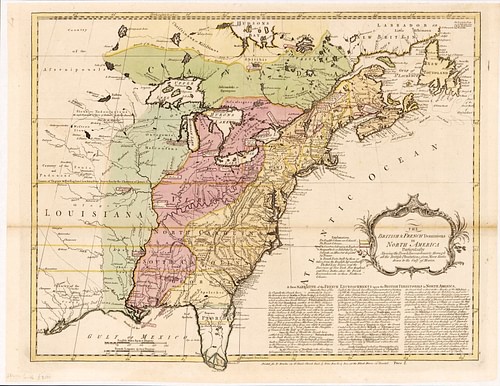

The establishment of the Middle and Southern English Colonies of North America was encouraged by the earlier English settlements of Jamestown Colony of Virginia in the south (founded 1607) and Plymouth Colony and, especially, Massachusetts Bay Colony in the north, founded 1620 and 1630 respectively.

These early colonies not only inspired more English to cross the Atlantic to start a new life in North America but, in the Middle Colonies especially, those of other nations. The colonies of New England grew primarily from the Massachusetts Bay Colony following Plymouth’s success. Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire were all developed by religious dissenters from Massachusetts Bay. The regions which would become the Middle Colonies were largely controlled by the Dutch until 1664 while the lands of the future Southern Colonies were inhabited by Native Americans who were displaced as Virginia’s tobacco crop and then Carolina’s rice crop became increasingly lucrative.

English colonists steadily purchased or otherwise deprived the Native Americans of their land and pushed out the Dutch to take control of the eastern seaboard of North America which allowed for profitable overseas trade. The following dates reflect the establishment of English control over a colony even though, in the case of the Middle Colonies, European settlement was already established.

Middle Colonies:

- Delaware – founded 1664

- New Jersey – founded 1664

- New York – founded 1664

- Pennsylvania – founded 1681

Southern Colonies:

- Virginia – founded 1607

- Maryland – founded 1632

- Carolina (later North and South Carolina) – founded 1663

- Georgia – founded 1733

- Florida (after 1763)

After 1619, slavery was steadily institutionalized in Virginia until slave laws were established by the House of Burgesses in the 1660s. By 1700, slavery was firmly entrenched as an indispensable aspect of the Southern Colonies’ economy and an important, though not vital, part of the economies of the Middle and New England Colonies.

After the French and Indian War (1754-1763), the colonies became more of a cohesive entity, though still maintaining their own governments and seeking their own interests, and this trend would continue through the American War of Independence (1775-1783), which would form the original 13 colonies into the early United States of America.

Early English Colonization

England was a latecomer in the colonization of the Americas. Spain was the first in 1492, followed by Portugal by 1500 in the southern regions and by France at about the same time to the north (present-day Canada and northern Maine). The English did not establish a settlement until the Roanoke Colony (1587-1590), whose first attempt, in 1585, failed quickly.

In 1607, the English founded Jamestown in Virginia and Popham Colony in present-day Maine; Popham failed after a little more than a year, and Virginia struggled to survive until it was saved by the strict governance of men like Thomas West, Lord De La Warr (l. 1577-1618) and Sir Thomas Dale (l. c. 1560-1619) and the tobacco crop of John Rolfe (l. 1585-1622). In New England (which had been so named by Jamestown colonist and explorer Captain John Smith in 1614), after Popham failed, no other attempts at colonization were made until the Plymouth Colony was established in 1620. Plymouth’s success encouraged further English colonization of New England establishing Merrymount Colony in 1624 and Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. Dissenters from Massachusetts Bay would establish the other New England Colonies between 1636-1638.

New England & the Dutch

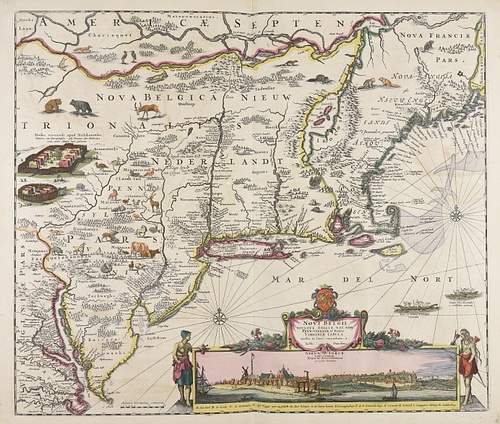

The Dutch had claimed the region between New England and the Virginia Patent by 1609 and were already in conflict with the English over trade by 1633 when Massachusetts Bay governor John Winthrop (l. c. 1588-1649) established a trading post on the Connecticut River upstream from a Dutch post to cut their access to the fur trade with Native Americans from the interior.

Unlike the colonies of New England, the Dutch colony of New Netherland followed the same model regarding religious and cultural tolerance as its mother country and so welcomed diverse religions and nationalities. Dutch wives and single women had more rights than those in the English colonies which encouraged migration from the one to the other so that, by c. 1650, New Netherland was the most diverse of any European settlement in North America with English colonists making up a small, but significant, minority.

The English crown had taken direct control of the Virginia colonies (those that developed from Jamestown) by 1624 but could not do the same with the New England Colonies which had established nearly autonomous local governments. In order to control the lucrative North American trade, the English government instituted the Navigation Acts in 1651 to discourage New England colonists from trading with other nations and restrict Dutch trade at the same time. The Navigation Acts stipulated:

- Only English ships (defined as a ship built by the English, owned and commanded by English subjects, and manned by a mainly English crew) could trade with English colonies.

- Certain commodities produced in the English colonies (primarily tobacco and sugar) could only be shipped to the mother country.

- All European goods arriving in the colonies had to pass through an English port where they would be taxed by customs officials.

Scholar Alan Taylor sums up the law’s purpose:

The Navigation Acts sought to enhance customs revenue collected in England, increase the flow of commerce enriching English merchants, stimulate English shipbuilding, and maximize the number of English sailors, swelling the reserve for the royal navy…According to the [English government’s] view, the government had every right, indeed the duty, to shape the economy to serve its needs for more revenue, ships, and men for use in war to drive other nations out of overseas markets. (258)

The Navigation Acts achieved their goal, but the Dutch continued to trade and New Netherland to expand until 1664 when England sent a fleet to take the region from them. The English and Dutch had already clashed in New England indirectly, but in 1652-1654 and 1664-1667 engaged in a number of naval battles which finally drove Dutch commercial interests from North America.

The Middle Colonies

New Netherland afterwards became the Province of New York, (named after the Duke of York, later King James II of England) and the Province of New Jersey (named for the Isle of Jersey in the English Channel) was established, also in 1664, and was divided between Scottish Protestants in the area of East Jersey (near New York) and English Quakers of West Jersey by the Delaware River. The colony was united as New Jersey in 1702 by the crown which took direct control through a royal charter.

The first English governor of New York was Richard Nicolls (l. 1624-1672) who wrote the first laws for the colony. These were later developed and enforced by governor Edmund Andros (l. 1637-1714) resulting in, among other changes, the loss of status for women. Taylor notes:

The imposition of English common law eroded the opportunities for Dutch colonial women to hold, manage, and dispose of property. As they became legally “covered” by their husbands’ identity, Dutch women dwindled as entrepreneurs, litigants, and testators. During the early 1600s, about forty-six women conducted commerce in their own names at Beverwyck [later Albany]; none did so in the Albany of 1700. (260)

The diversity of the region remained intact except where Native American rights were concerned. The Dutch had already pushed the native Algonquian and Lenni Lenape tribes from their lands and English policy continued this process. The Lenape were displaced from the region of modern-day Delaware by 1664 and, when the Province of Pennsylvania was established by the wealthy Quaker aristocrat William Penn (l. 1644-1718) in 1681, it became part of his colony until granted independent government and autonomy in 1701.

Penn welcomed Native Americans of all tribes to his colony which was founded on the Quaker ideal that every individual carried within a spark of the divine. Consequently, Native Americans were treated better in Penn’s colony than elsewhere and began migrating there, forming a buffer between the Middle Colonies and Southern Colonies.

The Southern Colonies

While New England had been developing, Jamestown Colony had been equally busy expanding settlements in Virginia. John Rolfe’s tobacco crop had proven itself the most profitable in the so-called New World, and in 1632, the aristocrat Cecilius Calvert, 2nd Baron of Baltimore, founded the Maryland Colony to cash in on the demand for tobacco. The colony was named after Henrietta Maria of France (l. 1609-1669), wife of King Charles I of England, who was a Roman Catholic, and Baltimore intended Maryland to be a haven for Catholics as well as a profitable venture in tobacco. Conflicts between the Catholic minority and protestant Puritans and Anglicans eventually led to the so-called “Plundering Time” of 1644-1646 during which Catholics were abused and priests deported. By 1704, Maryland was producing as much tobacco as Virginia and Catholicism had been outlawed in the interests of social stability; it would remain so until after the American War of Independence.

Stability was key to productivity and productivity, of course, to profit. Initially, the Virginia colonies operated on a class system of elite landowners, small farmers, and indentured servants until after 1619 when the first Africans were purchased from a Dutch ship by Sir George Yeardley (l. 1587-1627) to increase both productivity and profit. These Africans seem to initially have been treated along the lines of indentured servants, but after 1640 and through the 1660s racial chattel, slavery became institutionalized and the slave trade became more lucrative. Maryland and Virginia, known as the Chesapeake Colonies, both had a significant slave population by 1670 and their success encouraged the founding of the Province of Carolina to the south of Virginia.

Carolina, named for King Charles I, was established in 1663 in response to overcrowding and lack of opportunity in the English colony of Barbados. Wealthy English nobles, in a desire to provide financial opportunities for their sons, established a kind of manorial system of regional government which operated through a Council of Nobles known as the Lords Proprietor who encouraged religious tolerance, outlawed any attack – verbal or otherwise – on any religion, and mandated that small farmers would be subordinate to large plantation owners.

A group of settlements near Virginia objected to these rules, and in 1691, the Lords Proprietor established North Carolina as an independent colony to maintain peace with these settlers. The political faction known as the Goose Creek Men (so named because they lived along Goose Creek, a favored area of the elite) now dominated politics in South Carolina and could do as they wished, abolishing religious tolerance and instituting laws intended to keep them safe from Spanish attack from the south (where Spain had their colony in modern-day Florida), Native Americans from the interior, and the possibility of a slave revolt, as Carolina – both North and South – had large slave populations. Taylor writes:

Carolina’s early leaders concluded that the key to managing the local Indians was to recruit them as slave catchers by offering guns and ammunition as incentive…to pay for the weapons, the native clients raided other Indians for captives to sell as slaves – or they tracked and returned runaway Africans…If deprived of ammunition, the natives would suffer in their hunting and fall prey to slave-raiding by better-armed Indians more favored by their colonial supplier…By pushing the gun and slave trade, the Carolinians gained mastery over a network of native peoples, securing their own frontier and wreaking havoc on a widening array of Indians. Victimized peoples desperately sought their own trade connection to procure arms for defense; but to pay for those guns, they had to become raiders, preying upon still other natives, spreading the destruction hundreds of miles beyond Carolina. Drawn into the slave trade by degrees, the natives could not know, until too late, that it would virtually destroy them all. (228)

The destruction Taylor alludes to was made possible by the English policy of divide-and-conquer, which set the parties potentially hostile to the English against each other. Had the native tribes united against the English immigrants, they could have stopped incursions into their land, and if they had allied with the African slaves instead of catching and returning them to their masters, they would have had valuable allies. The English policy worked well, however, and the Africans and Native Americans were encouraged to distrust and betray each other while the English expanded their control of the land.

Georgia, named after King George II of England, was established from part of the Carolina Colony in 1733 by the politician and reformer James Oglethorpe (l. 1696-1785) who hoped to create a slave-free, utopian-type colony without religious animosity or gross social inequality. The Native American policies of the Carolina colonies had already removed most of the natives not killed by European disease and so there was plenty of land to be had but also a significant number who wished to settle there. The colonial government restricted new settlers to 50-acre tracts of land, not only in the interests of fairness but to prohibit the development of slavery in the colony. Large plantations could not function without slave labor and, since Georgia rejected slavery, they rejected plantation farming.

A number of colonists objected to this, however, claiming that they were being denied their individual liberty in being deprived of the right to own slaves. Taylor writes:

The Georgia dissidents rallied behind the revealing slogan “Liberty and Property Without Restrictions” – which explicitly linked the liberty of white men to their right to hold blacks as property. Until they could own slaves, the white Georgians considered themselves unfree. (242)

In 1751, the colonial government passed the law – over the objections of Oglethorpe – allowing slavery in the colony. A new government was created, modeled on that of Carolina, and more people were invited to settle, increasing the population from “3,000 whites and 600 blacks in 1752…to 18,000 whites and 15,000 blacks in 1775” (Taylor, 243). As more Africans were imported as slaves, however, and as recognition of the poor treatment given to Native Americans grew, fears of a joint Native American-African offensive became prevalent.

Conclusion

The Southern Colonies increased their efforts in the policy of divide-and-conquer by encouraging natives to not only capture and return runaway African slaves but also conquer neighboring tribes for slaves to be shipped to the West Indies. Harsher slave laws were passed, making it clear that a slave was property without any human rights, and slaves were encouraged to inform on one another regarding complaints about treatment by whites. Africans were therefore encouraged to betray fellow Africans just as Native Americans had been, further destroying any unified resistance to English colonization and expansion.

Sales of alcohol and guns to the natives, as well as repressive and unethical laws concerning Native American rights, neutralized many tribes as a threat while policies encouraging fear and enmity between African slaves and natives prevented the feared uprising. The English colonists had achieved the stability they required for productivity and profit, and by 1760, Taylor writes, “a relatively small group of whites became immensely rich, leisured, and politically powerful by exploiting a large and growing population of enslaved Africans” (243). At the same time, removal of native tribes, or their neutralization, opened up the “vast and fertile lands of Carolina and Georgia” providing “more room for common opportunity” for an influx of more settlers (Taylor, 243-244). These colonists were able to expand to the south after the English won the French and Indian War in 1763.

Spain had supported the French and their native allies against the English and their own native warriors, and when the French were defeated, Spain lost Florida to the English. England now had colonized the entire eastern seaboard of North America from New England to Florida. Slavery in the Middle Colonies, as well as increasingly exploitative policies regarding Native Americans became standard, and this same model was adhered to by the Southern Colonies, especially after Bacon's Rebellion in Virginia in 1676 during which black and white indentured servants banded together with slaves and poor whites in an attempt to overthrow the colonial government which favored the elite plantation owners.

Bacon’s Rebellion resulted in the abolishment of the indentured servant program, an increase in the importation of slaves, greater reliance on slave labor, and massive displacement of Native Americans of the region. Although slavery was not as vital to the economies of the New England and Middle Colonies, it was still practiced and considered not only an important aspect of financial success but profitable to the Africans as well.

Africans, as well as Native Americans, were thought to be in dire need of Christian salvation; even though missionary efforts to both groups seem to have been a low priority to the English colonists. The New England, Middle, and Southern Colonies of North America continued to develop and expand until, by the 1770s, the land-rich elite and many others were advocating for breaking away from English rule, famously insisting on their own right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness after depriving thousands of other non-English and non-white peoples of their own.