The Popham Colony (1607-1608 CE, also referred to as the Sagadahoc Colony) was an English settlement established in the present-day town of Phippsburg, State of Maine, USA, in August 1607 CE. The expedition which founded the site was comprised of about 100 men and boys whose principal goal was to establish a fort and build ships. The colonists arrived in August of 1607 CE, too late to plant crops, and many returned to England that fall when food began to run out. The remainder stayed until the fall of 1608 CE. Their leader, George Popham (l. 1550-1608 CE), had died in February 1608 CE and that fall his successor, Raleigh Gilbert, decided to return home upon hearing he had inherited his father's estate; the other colonists followed him home.

The venture was primarily backed by Popham's uncle Sir John Popham (l. 1531-1607 CE) who had died soon after the expedition had set sail and so a loss of funding also contributed to the decision to abandon the colony. The colonists succeeded in establishing their fort (Fort St. George) and a few of the planned structures and homes inside the walls as well as building a single ship (the Virginia, the first ocean-going sea vessel built in the Americas by the English), but having lost their leader and financial backer, suffering from inadequate food sources, and facing increasing animosity from the natives, Gilbert's decision to abandon the colony was approved of by the others.

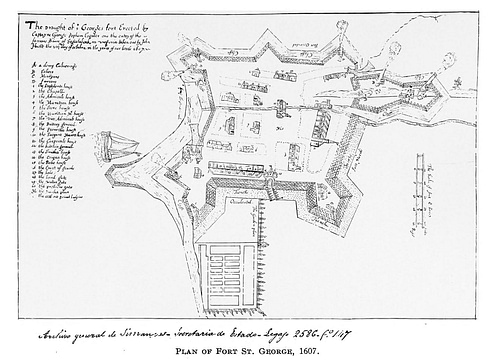

The location of the site was lost until 1888 CE when a map of the colony, drawn by a John Hunt (one of the colonists), was discovered in the archives in Simancas, Spain. Excavations at the site began in the 1960s CE, but no actual progress was made until 1994 CE when the archaeologist Jeffrey Brain began work there.

Between 1994-2013 CE, Brain's work has uncovered the outline of the fort, a number of structures, and numerous artifacts. The site is considered among the most significant in North America in regard to early English colonization as the colony only lasted 14 months before it was abandoned and so serves as a kind of time capsule of life there over 400 years ago.

Roanoke & Jamestown

After the Spanish, French, and others had already staked claims in North America, England made its first attempt in 1584 CE with the Amadas-Barlowe Expedition sent by Sir Walter Raleigh (l. c. 1552-1618 CE) to find suitable land for colonization which had not yet been claimed by a sovereign European nation. Captains Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe returned to England with a good report and a map of the region which Raleigh named Virginia in honor of Queen Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603 CE). The glowing report of the two captains encouraged ventures to capitalize on the so-called New World.

A settlement was established in 1585 CE on Roanoke Island off the coast of Virginia when the ships were unable to reach the mainland due to rough weather. This colony was led by one Ralph Lane (d. 1603 CE) who at first was able to form friendly relations with the natives but took advantage of their hospitality and finally attacked them for supplies. The colony would probably have been massacred afterwards but were rescued by Sir Francis Drake (l. c. 1540-1596 CE) who was passing by on his way back to England after raiding Spanish ships.

A second attempt was made at the Roanoke Colony in 1587 CE under John White, but this time the natives refused to help owing to Lane's earlier treatment. When supplies ran low, and with no crops planted, White returned to England for more. He was unable to return until 1590 CE, and then he found all the colonists had vanished; this is the so-called “Lost Colony of Roanoke”.

White had been delayed, in part at least, by the Spanish ships which regularly seized those of the English heading for the Americas. In 1588 CE, however, the Spanish Armada was destroyed, and English ships were free to travel across the Atlantic without fear of capture (at least by Spain). James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE) succeeded Elizabeth I and encouraged new attempts at colonizing North America. Two companies were created for this purpose: the London Company (also known as the Virginia Company) and the Plymouth Company.

James I granted charters to both but for different areas. The Virginia Company was free to colonize the region from the area of modern-day northern Florida up through the lower Hudson River Valley in New York State while the Plymouth Company was granted the rights from around New Brunswick, Maine down through upper New York State. The stretch of land in between these regions was left open to whichever company was most successful but would be taken by the Dutch before either company proved itself.

In 1606 CE, the Plymouth Company launched an expedition of one ship which was taken by the Spanish, who still had a significant number of operational ships, off Florida. In 1607 CE, the Virginia Company financed the expedition which would establish the Jamestown Colony of Virginia, and the same year, the Plymouth Company backed the one that founded Popham Colony. Both expeditions were made up entirely of men and both seemed to have believed the reports that the New World was teeming with gold one only had to step ashore and pocket to become fabulously wealthy.

The reality they were faced with was no such gold, wilderness, and – in the case of Jamestown – natives who were hostile to the immigrants because of their previous experiences with the colonies of Roanoke. Jamestown would lose 80% of its population between 1607-1610 CE when they were able to turn their fortunes around and go on to become the first successful English colony in North America; Popham Colony, though it suffered only one casualty (at least officially), would last only 14 months.

Arrival & Relations with the Natives

The Popham expedition, of two ships, was led by George Popham who commanded the Gift of God, and his second-in-command Raleigh Gilbert (nephew of Sir Walter Raleigh and son of Sir Humphrey Gilbert) in command of the Mary and John. They were guided by two Native Americans who had been kidnapped in 1605 CE and were being returned to their homes, Dehamda and Skitwarrers. The ships left England on 31 May 1607 CE and arrived off the coast of Maine on 8 August. Scholar Samuel Gardner Drake quotes Sir Ferdinando Gorges (l. c. 1565-1647 CE), one of the financial backers of the expedition, in describing the arrival:

As soon as the president [Popham] had taken notice of the place, and given order for landing the provisions, he dispatched away Captain Gilbert with Skitwarrers his guide, for the thorough discovery of the rivers and habitations of the natives, by whom he was brought to several of them, where he found civil entertainment, and kind respects, far from brutish or savage natures, so as they suddenly became familiar friends, especially by the means of Dehamda and Skitwarrers. (71)

Either at this meeting or shortly afterwards, the principal sagamores (chiefs) asked Popham to go, apparently, some distance to meet “Bashabas, who it seems was their king. They were prevented, however, by adverse weather, from that journey, and thus the promise to do so was unintentionally broken” (Drake, 71). This event might be interpreted as the beginning of problems between the English immigrants and the natives, but Gorges notes how the Bashabas later sent his son to trade with Popham, so it seems that, early on at least, relations between the two peoples were cordial.

Development & Conflict

Between August and October, John Hunt completed his draught of the plan for Fort St. George. It was to be a star-shaped fortification enclosing a community of homes and shops. On 8 October 1607 CE, the Mary and John left for England with Hunt and a copy of his map on board. Another copy, or the original, was left with Popham who had overseen the construction of the colony thus far. No crops had been planted, owing to their late arrival in the land, and they seem to have lived off what they could hunt, fish, or forage as well as the hospitality of the natives. When food began to run low in December 1607 CE, however, half the settlement sailed back to England aboard the Gift of God.

Hunt's map makes clear the intention to construct a full settlement behind the walls of Fort St. George, which would include a chapel, homes, a bakery, storehouse, market, and other structures. How much of this was completed is unknown. The extensive housing plans were abandoned when half the colonists left in December. Modern-day excavations have thus far uncovered the foundations of the storehouse, the line of the fortifications, the admiral's house (where Gilbert would have lived), and the building known as the buttery which stored liquor, wine, and other provisions.

The winter of 1607-1608 CE is reported to have been one of the worst in recent years, but Popham Colony, unlike Jamestown, suffered only one casualty: their leader George Popham who died on 5 February 1608 CE. He was succeeded by Raleigh Gilbert, age 24 or 25 at the time, who did not have the same high level of diplomatic skills with the natives as Popham had. According to accounts, Gilbert was ambitious but lacked leadership skills and was more interested in entertaining and enjoying himself than working toward a goal. Gilbert's lack of leadership skills alienated the Native Americans but what exactly happened is unclear. According to an account by the French Jesuit priest Pierre Biard, once Popham Colony was under Gilbert's command:

[The English] drove the savages away without ceremony; they beat, maltreated, and mis-used them outrageously and without restraint; consequently, these poor, abused people, anxious about the present, and dreading still greater evils in the future, determined, as the saying is, to kill the whelp ere its teeth and claws became stronger. The opportunity came one day when three boat-loads of [the English] went off to the fisheries. [The natives] followed in their boat, and approaching with a great show of friendliness, they go among them and at a given signal each one seizes his man and stabs him to death. Thus were eleven Englishmen dispatched. Others were intimidated and abandoned their enterprise the same year; they have not resumed it since. (45)

Drake mentions how one of the “melancholy accidents” to befall the settlement was the loss of the storehouse to fire in the winter of 1608 CE. He gives no cause for the fire, but Biard's account suggests that the Abenaki claimed credit for it. Biard's account is only suspect because of the animosity between the English and the French at this time and the penchant of French writers to cast the English in a bad light. If his report is accurate, however, then there were at least eleven more casualties of the Popham Colony than the official account which records only Popham's death.

The Virginia & Abandonment

It is unclear what was accomplished by the colony under Popham and what by Gilbert, but the central achievement of Popham Colony was the construction of the 30-ton pinnace (a three-masted, decked ship, which could be sailed or rowed), the Virginia of Sagadahoc. It was built to enable the settlers to explore the region further, but it does not seem to have been used for this purpose.

In September of 1608 CE, the Mary and John returned to the colony with the news that Raleigh Gilbert's older brother had died and he was now lord of his father's estate in Devon. Gilbert chose to return to England to claim his inheritance rather than continue to struggle at Popham, and the other colonists left with him aboard the Virginia and the Mary and John. The Virginia would make at least two other transatlantic crossings to supply Jamestown, but what happened to it afterwards is unknown.

When Father Biard and his company visited the site in 1611 CE, they were at first impressed by the abandoned English settlement, but the more they explored, the more their first impression changed:

Our people at once disembarked, wishing to see the English fort, for we had learned, on the way, that there was no one there. Now as everything is beautiful at first, this undertaking of the English had to be praised and extolled, and the conveniences of the place enumerated, each one pointing out what he valued the most. But a few days afterward they changed their views; for they saw that there was a fine opportunity for making a counter-fort there, which might have imprisoned them and cut them off from the sea and river; moreover, even if they had been left unmolested, they should not have enjoyed the advantages of the river, since it has several other mouths, and good ones. Some distance from there, furthermore, what is worse, we do not believe that, in six leagues of the surrounding country, there is a single acre of good, tillable land, the soil being nothing but stones and rocks. (33)

If one accepts Biard's account, then the Popham Colony would probably have been abandoned even if Gilbert had not received news of his inheritance, which deprived the colony of a leader. There is no evidence that Popham Colony was ever able to live off the land, and without Native American assistance, they would have had to have continued living off what they could hunt or take from the river or sea, especially after relations with the natives turned sour.

Conclusion

The Popham colonists who returned to England reported on the harsh winter when the river froze, the difficultly of the land in growing crops, and the hostility of the natives, all of which deterred further colonization plans for the region until the success of the Plymouth Colony was reported in 1622 CE. Within ten years of the arrival of the Mayflower in 1620 CE, the region known as New England was increasingly colonized by the English and some scholars claim that the reports of the Popham colonists provided the passengers of the Mayflower with a guide on how to proceed in the New World.

The site of Popham Colony was left alone, however, as other settlements grew up around it. Perhaps, as Biard claims, later colonists recognized the weaknesses of the site. During the American Civil War (1861-1865 CE), the US government built Fort Popham near the site and, later, Fort Baldwin but the center of the site itself remained undisturbed. There was no known record of what the settlement had even looked like until the discovery of Hunt's map in the archives of Simancas, Spain in 1888 CE. Scholars theorize the map was either stolen or copied by a Spanish spy in England when Hunt returned with it in the fall of 1607 CE.

The area was purchased by the State of Maine in 1924 CE and today forms part of the Fort Baldwin State Historic Site and park. In the 1960s CE, excavations were attempted at the site but came away with nothing of importance. It was not until 1994 CE, when archaeologist Jeffrey Brain was vacationing in Maine and became aware of Popham Colony, that excavations were begun in earnest.

Brain used Hunt's map to gauge where to dig and, between 1994-2013 CE, Brain and his team of specialists and volunteers excavated as much of the one-acre site as they could. Part of the original Fort St. George site, however, is now on land privately owned, and permission to continue excavations further onto these lands was refused. The story of the Popham Colony continues to engage scholars, however, and access to the lands might be granted at some point in the future, revealing other finds which will add to the history of the first English colony established in the region.