Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631 CE) was an English explorer, soldier, author, and early governor of the Jamestown Colony of Virginia between 1607-1609 CE. Smith had served as a mercenary in his younger years and was well-versed in military discipline. His written works continue to serve as important primary sources for the history of his time.

He was part of the expedition to establish the colony of Jamestown in 1607 CE and found himself surrounded by aristocrats, who had no experience with manual labor, and lower-class laborers who had no inclination to work. Both sets of colonists had arrived with him in Virginia under the impression that gold was to be had for free under every rock, leaf, and tree, and their disappointment in finding this was not so discouraged them. Smith took control of the colony and issued his famous edict, "He that will not work, shall not eat" which proved a significant motivator.

He is best known for his relationship with Pocahontas (l. c. 1596-1617 CE), daughter of the Powhatan chief Wahunsenacah (l. c. 1547-1618 CE, also known as Powhatan) who presided over the Powhatan Confederacy. Although Smith’s relationship with Pocahontas has been famously portrayed as romantic, there is no basis in fact for this as Pocahontas was, at most, 12 years old at the time and Smith was 27. Further, Smith himself gives no indication in his works of romantic involvement with her. Smith established a good working relationship with the Powhatans but left for England, without telling either Wahunsenacah or Pocahontas, in 1609 CE following an accident.

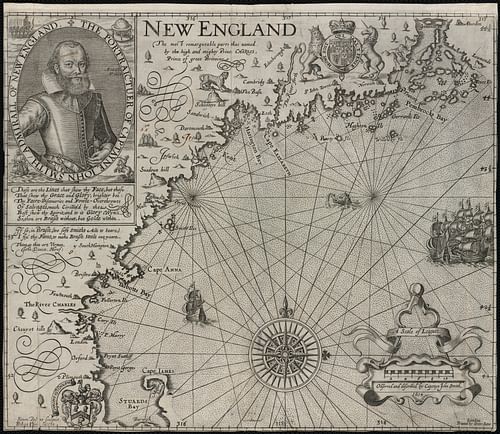

After he left Jamestown, Smith engaged in a number of other expeditions, most notably mapping the region of New England (which he named) in North America in 1614 CE. He was approached by the pilgrims who would go on to establish the Plymouth Colony as their military advisor, but they rejected him due to his price and their fear that his commanding personality might negatively influence their religious vision of the colony. He later mocked them for not at least using his maps, which would have saved them considerable time and effort.

Smith was a great self-promoter and prolific writer, penning a number of significant works on his experiences in North America as well as his younger years as a soldier. He is often criticized in the modern day for exaggeration or even outright fabrication of some passages in his works, but he remains a respected author and historical primary source for the details he provides of his time and his often-objective observations of the relationship between the immigrant English and the Native Americans.

Early Life & Adventures

John Smith was born in the village of Willoughby, England, Lincolnshire, in 1580 CE, the son of a tenant farmer. His father must have been rather well-off financially because Smith was educated at grammar school rather than having to work as a child. All other details of Smith’s life between childhood and the age of around 27 come from Smith himself and often have no outside corroboration.

It is for this reason that modern scholarship so often inserts disclaimers and qualifiers into discussions of his claims but, just because there is no objective corroboration for the events Smith says took place does not mean they did not happen. Smith’s contemporary, the writer William Strachey (l. 1572-1621 CE), also makes claims – such as seeing a blonde-haired Native American boy and noting this as proof that the "lost" Roanoke Colony was not lost but had been taken in by local Native Americans – which are uncorroborated but accepted, more or less, without question.

Scholar Charles C. Mann, however, notes how the difference between Smith and other writers is that Smith’s narratives consistently cast himself as the swashbuckling hero who, often against all odds, not only survives harrowing ordeals but prevails. Mann quotes a contemporary of Smith’s who observed, "it sounded much to the dimunition of his deeds, that he alone is the herald to publish and proclaim them" (65). Smith claims to have left home at the age of 16 after his father’s death to become a mercenary, fighting for France against Spain, and, afterwards, was a pirate in the Mediterranean and a mercenary sent against the Turks. Mann provides a list of Smith’s most impressive claims regarding his time abroad:

- He served in the Transylvanian Army, killed three Turks in single combat, and was knighted by the prince of Transylvania.

- He was captured and sold into slavery in the Ottoman Empire, killed his master, dressed in his clothes, and fled to Russia, then France, and finally Morocco.

- He joined a band of pirates who preyed on Spanish ships off West Africa. (65)

Later 19th-century CE scholars claimed that most of what Smith related was fictional, but this claim was challenged and discredited when it was pointed out that Smith’s spelling and penmanship were sub-par, and the names of people and places actually could be objectively corroborated once one deciphered them based on context clues. However he spent his younger years, he was back in England by 1604 CE and was associated with the Virginia Company of London and their efforts to colonize North America by 1606 CE.

Smith & Jamestown

Smith was chosen to accompany the 100 men and boys who made up the three-ship expedition to the New World, under the command of Captain Christopher Newport (l. 1561-1617 CE), to establish Jamestown. Spain had colonized the West Indies and South and Central America throughout the 16th century CE, and tales of the fabulous wealth of the Americas had been circulating in England for the past 100 years by the time the Virginia Company put together the expedition of 1607 CE. The members of the party, who had all grown up on the tales of the wealth of the New World, believed they had signed up for the fast-track to wealth as it was understood that gold and precious gems were to be found under rocks, behind trees, in shrubs all around the Americas and one needed to exert one’s self only so much as to pick it up.

Smith came from a working-class background and this significantly affected his relationship with many of the others who were aristocrats. Class distinctions were rigidly maintained in England at this time, and someone from the lower classes challenging a social superior could be whipped, jailed, or even executed. Smith ran into some trouble with Newport on the transatlantic crossing which caused Newport to charge him with mutiny. Smith spent most of the trip in the brig and was under order of execution until the ships reached the coast of North America in April 1607 CE and the orders from the Virginia Company were unsealed. Smith, it was discovered, had been named by the company as one of the colony’s leaders and so his death sentence was thrown out and he was set free.

Smith helped organize the temporary shelters for the colonists while they looked for a suitable spot to establish the colony. Spanish ships periodically raided the coasts and so an inland location was sought and finally located in May 1607 CE. The area was uninhabited by natives, which the colonists took as a good sign, but they later discovered this was because it was considered “bad land” in a marsh and plagued by mosquitoes and disease. Over half the colonists who established the colony in May were dead by September.

A large part of the problem with survival was the inability, or refusal, of the colonists to do any work to produce food. The survivors of the first expedition were already starving when Newport returned from England in January 1608 CE with 100 more colonists but no supplies to feed them as he had assumed, naturally, that the Jamestown Colony of Virginia would have worked out a food source by then. Smith had established a relationship with the Powhatans by this time, however, and the native tribes regularly fed the colonists what they could spare. This was never intended to be the main source for the settlers' food, however, and Smith consistently came into conflict with the aristocrats of the group, trying to impress upon them the need to produce their own.

Smith & Pocahontas

Wahunsenacah regarded the newcomers with suspicion but thought they might be useful allies against Spanish raids and so had offered them help in the form of food and supplies throughout 1607 CE, but he could not afford to feed the colonists at the expense of his own people. When food was not provided for them, the colonists took to stealing it from the natives, resulting in conflicts, and after one of these, the settlers captured a number of Wahunsenacah’s people. Smith met Pocahontas when, according to his account, she was ten years old and was sent with a warrior Rawhunt to negotiate the release of the captives. According to some accounts, the two became friends and afterwards taught each other their respective languages.

In December 1607 CE, Smith was taken by Opchanacanough (l. 1554-1646 CE), Wahunsenacah’s half-brother, and brought to the chief’s village. Here, according to Smith’s account, was where he was famously saved from execution by Pocahontas. Scholar David A. Price relates the now-familiar story as it was known in the 19th century CE:

There he was doomed to be put to death, by laying his head upon a stone, and beating out his brains with clubs. He was led to the place of execution, and his head bowed down for the purpose of death, when Pocahontas, the king’s darling daughter, then about thirteen years of age, whose entreaties for his life had been ineffectual, rushed between him and his executioner, and folding his head in her arms, and laying hers upon it, arrested the fatal blow. Her father was then prevailed on to spare his life. (68)

This famous account comes from Smith’s own in his 1624 CE work The General History of Virginia where he writes:

A long consultation was held [among the natives] but the conclusion was, two great stones were brought before Powhatan: then as many as could laid hands on him [Smith], dragged him to them, and thereon laid his head, and being ready with their clubs, to beat out his brains, Pocahontas, the King’s dearest daughter, when no entreaty could prevail, got his head in her arms and laid her own upon his to save him from death; whereat the Emperor [Wahunsenacah] was contented he should live to make him hatchets, and her bells, beads, and copper. (321)

Modern scholarship maintains that this event either never happened or was a ritual, establishing Smith as part of the tribe, which he misinterpreted. In Smith’s 1608 CE account of his apprehension by Opchanacanough and journey to Wahunsenacah’s village, he makes no mention of Pocahontas or any attempt at executing him. The story first appears in a letter he wrote to Queen Anne of Denmark (wife of James I of England) in 1616 CE when Pocahontas and her husband John Rolfe (l. 1585-1622 CE) were visiting the country on a promotional tour for the colony.

It is now thought that, if the event happened, it was a death-and-rebirth ritual through which Smith “died” to his old life and was “reborn” as a member of the Powhatan Confederacy. Scholars have claimed that the event probably never occurred, however, because Pocahontas, as a young female, would not have been allowed to participate in or even witness such a ritual. Others have countered this claim, however, noting that Smith wrote his letter to Queen Anne when Pocahontas herself was in the country and able to call him out if he were lying.

No one disputes that Smith and Pocahontas were on friendly terms, however, nor that Smith established an effective working relationship with her father. Wahunsenacah is said to have expressed genuine affection for Smith even though his behavior was often exasperating or unacceptable. Smith stopped his people from stealing from the Powhatans and, in 1608 CE, instituted his famous policy of "he that will not work, shall not eat" which finally motivated the colonists to make an attempt to provide for themselves.

The Pilgrims & New England

Smith was injured in a gunpowder explosion in the fall of 1609 CE and had to return to England for treatment. He never sent word of his imminent departure to the Powhatans and the colonists later told Wahunsenacah and Pocahontas that he had died (why they told them this is unclear). His former relationship with the Powhatans had cooled by this time as food was still scarce, and the settlers were again stealing from the natives and demanding supplies. Smith himself was guilty of this, often demanding food from nearby Powhatan villages at gunpoint.

Once he recovered from his injuries back in England, Smith wrote further of his adventures in North America and published his works along with a number of maps of the area. He was then hired to map the northern regions of North America and was sent on an expedition there in 1614 CE, naming the area New England and also giving names to specific places along the coast such as Plymouth. This expedition included one Captain Thomas Hunt who was left to conclude business when Smith sailed back for England. Hunt kidnapped a number of Native Americans (among them, Squanto) to sell into slavery in Europe; an act denounced by Smith, who then barred Hunt from further commerce in the Americas.

In 1616 CE, Pocahontas, with her husband John Rolfe, young son Thomas, and members of her tribe, visited England on the promotional tour mentioned above. Smith avoided his former friend for most of her stay, only finally visiting her in 1617 CE before she was to return to Virginia. Pocahontas chastised Smith for dereliction of duty in not honoring agreements made with her father and for leaving Jamestown without telling them. Scholar Paula Gunn Allen quotes Pocahontas telling Smith:

They did tell us always you were dead, and I knew no other [truth] until I came [here] to Plymouth. Yet Powhatan did command [us] to seek you and know the truth because your countrymen will lie much. (292)

The meeting is recounted by Smith himself and yet the meaning of her words seems lost on him as he never responds to her accusations or criticism and certainly gives no indication he took them to heart or apologized. By all accounts, however, the meeting did not go well, and Pocahontas set sail for North America. She would never reach home, however, dying aboard ship – possibly from pneumonia – before even reaching the open sea.

Afterwards, Smith was approached by a group of religious separatists (later known as pilgrims) asking if he would be interested in joining them on an expedition to the New World to establish a colony. Smith expressed interest in the position of military advisor and guide, but the pilgrims rethought their offer and rejected him. Their goal was to create a religious community, and they feared Smith’s strong personality and "worldly nature" might interfere with this. Scholar Nathaniel Philbrick quotes Smith’s reaction:

"They would not…have any knowledge by any but themselves," Smith wrote, "pretending only religion their governor and frugality their counsel when indeed it was…because…they would have no superiors" …As Smith later wrote, much of the suffering that lay ahead for the pilgrims could easily have been avoided if they had seen fit to pay for his services or, at the very least, consult his map. (59)

Myles Standish (l. c. 1584-1656 CE) was chosen in Smith’s place while Smith continued to complain about the pilgrims and their arrogance from his home in England.

Conclusion

Smith published his General History of Virginia in 1624 CE, still hoping for employment with some venture which would return him to North America. He had tried to return himself in 1615 CE but was taken prisoner by French pirates and held captive until he managed to escape and find his way back to England. In his History, Smith advocated for military discipline and force in colonizing North America, suggesting himself as coordinator and director of this policy.

Smith’s advocacy came in response to the so-called Indian Massacre of 1622 CE during which Opchanacanough gathered the tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy for a concentrated attack on Jamestown, killing over 300 colonists, and initiating the Second Powhatan War (1622-1626 CE). In the Fourth Book of his work, Smith offers his services to the Virginia Company in helping to resolve the problem of the "savages" and establish peace:

If you please, I may be transported with a hundred soldiers and thirty sailors by the next Michaelmas, with victual, munition, and such necessary provision, by God’s assistance, we would endeavor to force the savages to leave their country. (491)

No one took Smith up on his offer, however, and he remained in England until he died of natural causes in 1631 CE. His works continued to be published and remained bestsellers, linking Smith forever with the first successful English colony in North America and establishing him as its first effective governor. In time, he became a larger-than-life figure to the settlers of New England and, although detractors continue to criticize the accuracy of his works, remains one of the most popular, and often controversial, figures of Colonial America.