Wahunsenacah, also known as Chief Powhatan (l. c. 1547 - c. 1618) was the head of the Powhatan Confederacy of Native Americans who inhabited the region of the modern-day State of Virginia, USA, which they knew by the name of Tsenacommacah (densely populated land).

He is also known by his title Mamanatowick (Great Chief) as well as by different spellings of his name translated from his native Algonquian into English as Wahunsenasawk, Wahunsenacoq, Wahunsenakah, and other variations along the same lines. He is best known as the father of Pocahontas (l. c. 1596-1617) and less well-known as the half-brother of Opchanacanough (l. 1554-1646) who waged the last two Anglo-Powhatan Wars against the English invaders.

Nothing is known of his father, but he inherited leadership of six tribes in the region from his mother (as the Powhatans were a matrilineal society) before c. 1570. He then expanded his kingdom through the assassination of other chiefs, warfare, or diplomacy until, by c. 1607, he was the leader of over 30 different tribes who paid him tribute for protection against other indigenous tribes which were not aligned with the Powhatan, notably the Iroquois Confederacy.

Almost nothing is known of his life prior to 1607 when the Jamestown Colony of Virginia was established by the English. He befriended Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631) and attempted to ally himself with the English against the Spanish and other native tribes, but relations deteriorated as the Jamestown colonists continued to demand more from their neighbors while simultaneously abusing them.

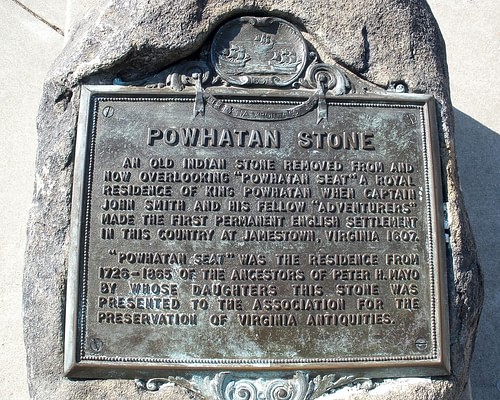

Wahunsenacah launched the First Powhatan War in 1610 in response to land theft by the colonists which ended in 1614 with the marriage of Pocahontas to the tobacco farmer John Rolfe (l. 1585-1622). The marriage established the so-called Peace of Pocahontas (1614-1622), which was broken by Opchanacanough in 1622, setting off the Second Powhatan War (1622-1626). By that time, Wahunsenacah had died. He is remembered in the present day through place names in Virginia, statuary, monuments, and historic sites associated with his life. His capital, Werowocomoco, long considered to have been located in modern-day Wicomico, Gloucester County, Virginia, was definitively identified west of that area on Purtan Bay in 2003, and excavations are ongoing.

Powhatan Confederacy

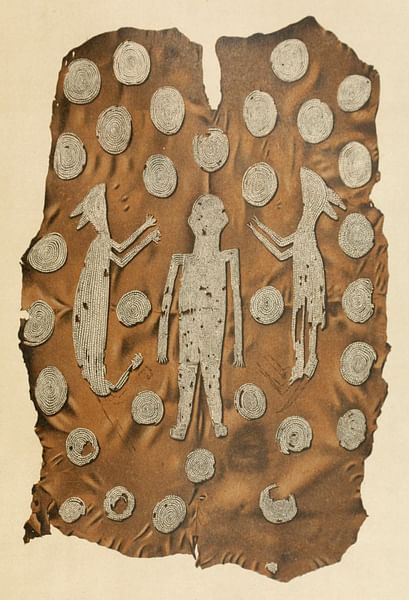

Long before the Powhatan Confederacy was formed under Wahunsenacah, the indigenous tribes who would form it had lived in the region as separate political, cultural, and martial entities. Native American habitation of the area has been traced back over 12,000 years and shows gradual development from a nomadic to semi-nomadic culture. Scholar Rick Sapp comments:

They cleared fields by felling, girdling, or firing trees at the base and then setting fire to the slash and stumps. A site became unusable when soil productivity declined and local fish and game such as buffalo (which migrated into this area before 1400) were depleted. The bands then moved on. In every new location, the people used fire to clear virgin land. They also used fire to maintain extensive areas of open game habitat, called "barrens". (290)

Men were responsible for hunting and warfare while women planted, tended, and harvested crops. When the men left on hunting expeditions, the women went before them to construct temporary camps. In time, certain areas were established as permanent communities, and one of these permanent settlements was Werowocomoco, a name derived from the Algonquian word for "leader" – weroance – and for "settlement" – komakah – given as "village of the leader". Werowocomoco may have already been the center of Powhatan government prior to Wahunsenacah’s reign.

As a matrilineal society, one’s family name and title were passed down through the female’s bloodline, and women chose the elders, members of the tribal council, and the chief. Wahunsenacah’s mother’s name is unknown but she would have been a powerful member of the tribe, probably even the chief, and conferred that title on her son at some point prior to c. 1570. He also inherited the responsibility for presiding over not only his own tribe of the Powhatan but the Appamattuck, Arrohateck, Chiskiack, Mattaponi, and Pamunkey.

The Native American tribes were not a cohesive or unified society. Each tribe was its own nation and made war on others. These were not wars of conquest but waged for honor, power, prestige, or to avenge a wrong. Scholar Alan Taylor comments:

Lacking property to plunder, the Indians primarily fought for scalps or captives, both to boost their own honor and to degrade that of their enemies…Although chronic, Algonquian warfare killed relatively few people by English standards. The natives waged short raids intended to kill a few warriors, take some captives, and humiliate a rival, then beat a hasty retreat homeward to celebrate. (127)

The tribes of the region they knew as Tsenacommacah engaged in this kind of warfare regularly. The Iroquois Confederacy (also known as the Haudenosaunee) to the north had formed a league of tribes to end these conflicts and empower themselves at some point in the 12th century. Their success may have inspired Wahunsenacah to form his own league, especially since the Iroquois were among the hostile tribes raiding Powhatan lands.

With the six tribes under his control, Wahunsenacah embarked on a policy of expansion from Werowocomoco. His methods were often brutal – raids which killed the tribe’s chief and replaced him with one of Wahunsenacah’s sons or a trusted member of his extended family – but he also employed diplomacy and bribery to bring a tribe under his control. Each tribe had its own weroance who submitted to Wahunsenacah and paid him tribute. This tribute, which included crops such as corn, beans, and squash (the so-called Three Sisters) deerskins and furs, was then distributed equitably among the tribes of the confederacy. This system provided the tribes with regular supplies of food as well as surplus for lean seasons.

The Powhatan Confederacy also maintained the safety and security of the unified tribes against outsiders. In order to maintain unity, Wahunsenacah organized multi-tribal, large-scale hunts each winter, sending his people toward the interior where they were free to raid the villages and take the scalps of tribes outside of the confederacy. Men who needed to prove themselves as warriors were able to thereby meet this need without causing conflict within the confederacy. Wahunsenacah’s policy was so successful that, by 1607, he was the leader of over 30 different tribes in Tsenacommacah.

Jamestown & the Powhatan

The Spanish had colonized the West Indies, South and Central America throughout the 16th century and made periodic raids up the coast of North America, kidnapping natives to sell into slavery. When the English arrived in Tsenacommacah in May of 1607, Wahunsenacah thought they might prove useful allies against not only the Spanish raiders but the Iroquois and other hostile nations. The English chose to establish Jamestown in a swamp that Wahunsenacah had no use for as it was considered 'bad land', poor for agriculture and only good for generating disease, and so he had no problem with the English settling there. He allowed the settlement to establish itself, but it would be inaccurate to say he actually welcomed them.

He did feel badly for the inept and poorly prepared English, however, and instructed his people to provide them with food. One of the first tribes to interact with the colonists was the Kecoughtans who invited the English to dine with them. They were appalled at their guests’ lack of manners as they grabbed at sacks of corn until it was made clear the invitation was for a civilized sit-down dinner at which they would be served.

The colonists had come to believe the Spanish propaganda that the so-called New World was laden with gold and one only needed to pick the plentiful pieces up to become wealthy. The expedition, of around 100 men and boys, was therefore made up largely of individuals who expected to get rich quick without expending any effort. The initial gesture of generosity from the Powhatans, therefore, was taken as an invitation to continue looking to them for food.

Wahunsenacah had most likely ordered the Kecoughtans to supply the colonists out of their surplus and, when this was exhausted, the colonists began stealing food from nearby villages or trading tools, weapons, clothing, and other items in exchange for corn and beans. To discourage this practice, and encourage the English to fend for themselves, the natives began raising prices but all this accomplished was to increase theft which finally led to conflict and the taking of prisoners.

John Smith & Wahunsenacah

John Smith first met Pocahontas when she came as part of a delegation sent by Wahunsenacah to negotiate the release of some Powhatans who had been captured by the colonists and were being held at Jamestown. They initially communicated through hand gestures but, according to some accounts, learned some bits of each other’s language through later interactions. While on an exploration of the interior, Smith was taken by Wahunsenacah’s half-brother Opchanacanough and brought to Werowocomoco where he was presented to Wahunsenacah. Smith provides the first written account of what the great chief looked like:

Arriving at Werowocomoco, their Emperor [Wahunsenacah] was proudly lying upon a bedstead a foot high upon ten or twelve mats, richly hung with many chains of great pearls about his neck and covered with a great covering of racoon skins. At his head sat a woman, at his feet another, on each side sitting upon a mat upon the ground were ranged his chief men on each side of the fire, ten in a rank, and behind them as many young women, each a great chain of white beads over their shoulders, their heads painted in red and he with such a grave and majestical countenance as drove me into admiration to see such a state in a naked savage. He kindly welcomed me with good words and great platters of sundry victuals, assuring me his friendship, and my liberty within four days. (17)

Smith’s initial account of this meeting makes no mention of Pocahontas at all. The famous story of Smith’s capture by Chief Powhatan and how he was saved from execution by Pocahontas first appears in a letter Smith wrote to Queen Anne of Denmark (wife of James I of England) in 1616 when Pocahontas visited England as the wife of John Rolfe, and it was repeated in Smith’s The General History of Virginia, published in 1624. The scholarly consensus is that Smith’s account of his rescue is either a fabrication or Smith misinterpreted a death-and-rebirth ritual intended to symbolically 'kill' him, severing him from his old life, and welcome him into the tribe as a werowance of the English whom Wahunsenacah regarded as another tribe which could be added to his confederacy.

Wahunsenacah was able to make clear to Smith that he wanted him as an ally and, as promised, released him afterwards. Smith then took firmer control of the colony, prohibited theft from the natives, and forced the settlers to work in order to eat. Relations improved for a time until word was brought back from England by Captain Christopher Newport (l. 1561-1617) that the Virginia Company of London – the group who had financed the Jamestown expedition – wanted Smith and Newport to make Wahunsenacah a subject of King James I through a ritual in which he would be crowned an English prince.

Smith adamantly rejected this course, pointing out that Wahunsenacah was a sovereign in his own right and trying to make him subject to the English king could only cause trouble. Still, he and Newport and the others had no choice but to follow the directives of the company and Wahunsenacah was informed that they wanted to crown him in a formal ceremony. He was asked to come to Jamestown but refused, telling them that it was undignified for a king to make such a concession to commoners and they would have to come to Werowocomoco.

The ritual did not go well because Wahunsenacah either pretended to or truly did not understand what the ritual was about or what the crown was for. In order for him to accept his position as a subject of King James I, he was supposed to kneel so the crown could be placed on his head. As a king, however, Wahunsenacah would kneel to no one and so the colonists surrounding him tried to lean on his shoulders to force him down. He was a tall man, however, and their efforts only made him stoop somewhat so that the crown could hastily be placed and then one of the men fired off a weapon in celebration, a cannon from the nearby ship Discovery fired in answer, and the ritual was quickly concluded. Wahunsenacah seems to have regarded the entire event as an exchange of gifts – and nothing more – since he afterwards gave Captain Newport his deerskin shirt and a pair of moccasins in return for the crown and cloak he had received.

De La Warr & First Powhatan War

The colonists seem to have now understood Wahunsenacah and his people as subjects of their king, like themselves, while Wahunsenacah acknowledged no such thing. Throughout 1609, colonists continued to expect food from the neighboring tribes, and relations soured. Problems were exacerbated by the influx of more settlers so that, by August of 1609, there were over 500 colonists at Jamestown, all of whom required food and shelter, necessitating expansion further into Powhatan lands. Smith was injured in a gunpowder explosion in October 1609 and returned to England for treatment. His relationship with the Powhatan chief had deteriorated by then to the point that he did not even tell him he was leaving. The colonists would later tell the Powhatans, for some reason, that Smith had died.

Wahunsenacah ordered the colonists to remain within the walls of their fortified town and gave his warriors leave to kill those who ventured out. This policy contributed to what is known as the Starving Time during which over 80% of the Jamestown population died and those who survived only did so by eating vermin, dogs, horses, and, finally, corpses. In May 1610, a supply ship arrived bringing the new governor Sir Thomas Gates (l. c. 1585-1622) who found only 60 settlers left alive. He ordered the colony abandoned and was taking the survivors back to England when another ship arrived carrying the aristocrat Thomas West, Lord De La Warr (l. 1577-1618) who took control and ordered the colony re-established.

De La Warr took a radically different approach to Anglo-Powhatan relations, making demands on Wahunsenacah and expecting compliance. His policies of no compromise resulted in the First Powhatan War (1610-1614). De La Warr fell ill and returned to England in 1613, handing his authority over to Sir Samuel Argall (l. c. 1580-1626). Argall continued West’s policies and kidnapped Pocahontas in 1613, holding her for ransom first at Jamestown and then at the recently established colony of Henricus.

John Rolfe, who had arrived on the same ship as Gates in 1610, had by this time cultivated his profitable tobacco crop on his plantation across the river from Henricus and met Pocahontas there. She converted to Christianity, took the name Rebecca, and married Rolfe in April 1614 with her father’s blessing. The First Powhatan War ended with their marriage and the Peace of Pocahontas was established.

Conclusion

Rolfe, Pocahontas, and their young son Thomas went to England in 1616 on a promotional tour to generate further investment in Jamestown, and she died there, probably of pneumonia. Thomas was left in the care of Rolfe’s brother. Wahunsenacah mourned the loss of his favorite daughter but kept the peace in honor of her son. He stepped down as chief c. 1617 and his younger brother Opitchapam briefly succeeded him but did not have the confidence of the elders that Opchanacanough had and so the latter became chief. Wahunsenacah died the next year and was buried with all honors.

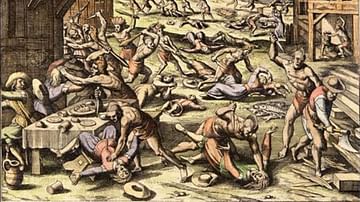

Opchanacanough maintained the peace, but the lucrative tobacco crop meant even more prime land taken from the Powhatans and, in 1622, he attacked the settlements, killing over 300 colonists in the first raid known as the Indian Massacre of 1622. The war continued until 1626 when Opchanacanough sued for peace, but hostilities continued afterwards. Opchanacanough launched the Third Powhatan war in 1644 in a final attempt to drive the English out but was defeated, captured, and then killed in 1646, ending the war. The treaty signed by his successor dissolved the Powhatan Confederacy and removed the natives to reservations.

After Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676, Native American lands shrank even further, and in the present day, only the Mattaponi and Pamunkey tribes still retain their 17th-century land grants. The land Wahunsenacah ruled over is now the highly-developed State of Virginia, but he is remembered as its former king through sites dedicated in his honor (such as the Powhatan Stone) and areas identified as closely associated with him like Werowocomoco. His descendants, still living in the region, have only recently been granted official recognition by the Federal Government of the United States as Native American tribes but continue to fight for the respect they deserve.