John Winthrop (l. c. 1588-1649 CE) was an English lawyer best known as the Puritan leader of the first large wave of the Great Migration of Puritans from England to North America in 1630 CE and governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony (founded in 1628 CE) which they settled and expanded upon, and the founder of the city of Boston. Winthrop is also known for the conflicts between his government and religious dissenters such as Roger Williams (l. 1603-1683 CE), Anne Hutchinson (l. 1591-1643 CE), and Thomas Hooker (l. 1586-1647 CE), who were expelled by the colony and settled the regions now known as Rhode Island and Connecticut.

Winthrop served 18 terms as Massachusetts Bay Colony's governor from the time of his arrival until 1649 CE. As a strict Puritan, he came to embody Puritan virtues and values as well as their intolerance for dissenting views. He was instrumental not only in establishing the colony and expanding it but for his written works, including a history of the colonization of New England, his famous A Model of Christian Charity, and A Little Speech on Liberty defining the difference between “natural” and “civil” freedom.

His policy toward the Native Americans was marked at first by condescension and then brutality in the Pequot War (1636-1638 CE), which nearly exterminated the Pequot tribe. His proclamation giving thanks and declaring a day of Thanksgiving for the massacre of over 700 Pequots is remembered today by Native Americans who observe a Day of Mourning annually on the holiday of Thanksgiving.

He supported the practice of slavery, owned slaves, and assisted in the sale and transport of Pequots as slaves to other regions. He is primarily referenced in the modern day, however, for A Model of Christian Charity, which later writers and U.S. presidents have referenced in holding the United States up as a "city on a hill" which commands the attention and respect of the rest of the world and has encouraged the concept of American Exceptionalism.

Early Life & Belief

John Winthrop was born in Suffolk, England to upper-class landowning parents, Adam and Anne Winthrop in 1588 CE. His father became a director for Trinity College, Cambridge, and education was valued highly in the home. Winthrop was tutored privately, attended public school, and was accepted to Trinity College at the age of 14 in 1602 CE. At Trinity, he would meet two of the most important names in the later development of Puritanism in North America, John Cotton (l. 1585-1652 CE), the master Puritan theologian, and preacher John Wheelwright (l. c. 1592-1679 CE), who was expelled with Anne Hutchinson from the Massachusetts Bay Colony over religious differences.

Religion dominated Winthrop's youth, and he was already a Puritan devotee by the time he was 15 (as evidenced by his journals). Puritans opposed the practices and policies of the Anglican Church on the grounds that it had not gone far enough to purge itself of Catholic elements during the Protestant Reformation (1517-1648 CE). Scholar Alan Taylor comments:

Begun as an epithet, "Puritan" persists in scholarship to name the broad movement of diverse people who shared a conviction that the Protestant Reformation remained incomplete in England. Because the monarchs favored religious compromise and inclusion, the Anglican Church was, in the horrified words of one Puritan, "a mingle-mangle" of Protestant and Catholic doctrines and ceremonies. The ecclesiastical structure of bishops and archbishops remained Catholic except for the substitution at the top of the king for the pope. (160-161)

Puritans wished to 'purify' the Church of the Catholic elements they found offensive and 'not of God' and adhere to a simpler form of Christianity based solely on the Bible. At Trinity, Winthrop associated primarily with others who shared his Puritan beliefs and, through these people, met his wives. He married his first wife, Mary Forth, in 1605 CE, and they had five children (three of whom would survive to maturity) before Mary died in childbirth in 1615 CE. He quickly remarried one Thomasine Clopton that same year and supported his family by practicing law (though he never passed the bar). In 1616 CE, Thomasine also died in childbirth, and he married his third wife, Margaret Tyndal, in 1618 CE, taking up residence at the Winthrop family estate, Groton Manor. His eldest son, John Winthrop the Younger (l. 1606-1676 CE, one of the surviving children of his first marriage), followed his father's example in education and pursuing a career in law and would later play a major role in the colonization of New England.

The family continued their devotion to the Puritan vision of Christianity even though, increasingly, this caused problems for adherents due to persecutions by the Anglican Church. The Anglican Church had replaced Roman Catholicism under the reign of Henry VIII of England (1509-1547 CE) and, from that time, the English monarch was the head of the Church. Criticism of the Church became synonymous with treason against the throne during the reign of Elizabeth I of England (1558-1603 CE) and persecutions became standard under James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE). When Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649 CE) came to the throne, the situation for Puritans only became worse. Puritans were persecuted on a regular basis, and in 1629 CE, Charles I dissolved Parliament so he could rule without interference. Many Puritans lost their jobs at this time, especially those who held positions relating to the government or the Church, and Winthrop was among these.

The Great Migration & Expansion

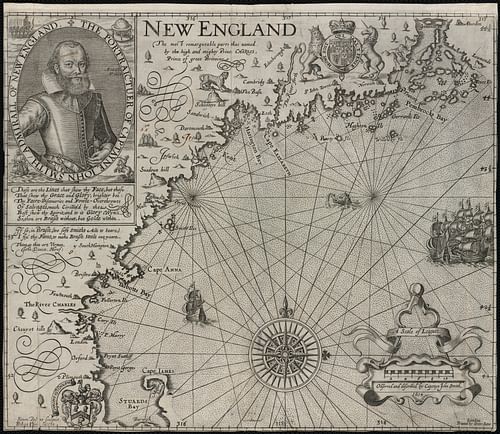

England had been engaged in attempts to colonize North America since the 1580s CE with varying degrees of success. The Roanoke Colony had failed, and the Jamestown Colony of Virginia, founded in 1607 CE, lost 80% of its population before it found its footing after 1610 CE. The Popham Colony of Maine, also founded in 1607 CE, only lasted 14 months before it was abandoned. The Plymouth Colony, however, founded in 1620 CE, was able to establish itself within a year in Massachusetts, and its colonists (who were Puritan Separatists, those who had completely separated from the Church instead of working for reform) sent back glowing reports of a boundless land of opportunity, which encouraged others to follow their example.

The Massachusetts Bay Company was formed to finance an expedition to the New World and sent an advance crew, led by John Endicott (l. c. 1600-1665 CE), to establish what would become the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Endicott, the first governor of the colony, was a Puritan Separatist known for his quick temper and intolerance. One of his first acts upon arriving in Massachusetts was in support of a raid by the Plymouth Colony on the unorthodox Merrymount Colony led by Thomas Morton (l. c. 1579-1647 CE) which was, nominally at least, Anglican.

While Endicott was at work in North America, the Massachusetts Bay Company shareholders in England elected Winthrop as governor of the new colony. Winthrop left England, in the company of two of his sons, aboard the ship Arbella in April 1630 CE, leading three other ships carrying around 700 Puritan colonists. Either just before departure, or once underway, Winthrop delivered his famous sermon A Model of Christian Charity in which he emphasized the importance of communal work toward a single goal and what was at stake in the venture they had embarked upon:

We must be knit together in this work as one man, we must entertain each other in brotherly affection, we must be willing to abridge ourselves of our superfluities for the supply of others' necessities, we must uphold a familiar commerce together in all meekness, gentleness, patience, and liberality, we must delight in each other, make others' conditions our own, rejoice together, mourn together, labor, and suffer together, always having before our eyes our commission and community in the work, our community as members of the same body, so shall we keep the unity of the spirit in the bond of peace; the Lord will be our God and delight to dwell among us, as his own people, and will command a blessing upon us in all our ways so that we shall see much more of his wisdom, power, goodness, and truth than formerly we have been acquainted with; we shall find that the God of Israel is among us, when ten of us shall be able to resist a thousand of our enemies, when he shall make us a praise and glory, that men shall say of succeeding plantations: the Lord make it like that of New England; for we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us; so that if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken and so cause him to withdraw his present help from us, we shall be made a story and a by-word through the world, we shall open the mouths of enemies to speak evil of the ways of God and all professors for God's sake; we shall shame the faces of many of God's worthy servants, and cause their prayers to be turned into curses upon us till we be consumed out of the good land whither we are going. (Hall, 169)

This concept of the colony as a 'city on a hill', which all the world was watching and the vital importance of its success for the glory of God, would inform the colony's policies and Winthrop's governance. Only those of like-mind who were willing to work hard with others toward success would be tolerated in the colony. Any those who caused dissent or raised questions concerning theology or Christian practice would be sent away.

Winthrop and his fleet arrived in June 1630 CE and were greeted by Endicott at Salem. Winthrop dismissed Salem as lacking for his purposes and established a new settlement at a spot which Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631 CE) of Jamestown fame had noted on his maps of 1614 CE as the best; this became the city of Boston. In order to keep from overcrowding (and also to prevent themselves from becoming an easy target for attack), Winthrop organized expeditions up and down the Charles River which established Cambridge, Charlestown, Dorchester, Medford, Roxbury, and Watertown.

Between their arrival and the spring of 1631 CE, these colonies lost about a quarter of their population to disease and other causes but persisted in the work of establishing and developing a shining example of a Puritan Christian community. Winthrop led by example, building his own home and helping others with theirs as well as in the construction of public buildings. As governor, he could have assigned menial labor to others, but he lived the words he had preached in his sermon and committed himself to the same workload as everyone else.

Governance & Conflict

Winthrop was not only a diligent laborer in every respect but highly educated, well-versed in the Bible, a student of history, and an astute observer of recent events. He was aware of how, when Jamestown finally succeeded, King James I had revoked the private charter of the Virginia Company which had financed it and taken direct control of the colony through a royal charter. To prevent this from happening to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Winthrop had taken the charter with him, rather than turning it over to the clerks, when he left England. If Charles I wished to follow the precedent set by James I, he would have to send emissaries to North America to revoke the charter.

This single action placed the original document, which validated and legalized the colony, in Winthrop's hands, effectively shifting governmental authority from England to New England. It also protected the colony from later legal attacks in the 1630s CE brought by the lawyer and former leader of the Merrymount Colony, Thomas Morton, who had been banished from North America by Winthrop in 1630 CE and sent back to England. Morton actually succeeded in his lawsuit to have the charter revoked, but his efforts came to nothing because, among other reasons, the actual charter was in Winthrop's hands and it was considered too much effort and trouble to send anyone from England to get it back.

Winthrop founded his colony as a Republic in which magistrates are elected by popular vote but remained true to his vision of establishing and developing a community of like-minded Puritans. His policies in this regard are best exemplified through his banishment of Roger Williams, a Puritan separatist, who first raised the voice of dissent in opposition to the Puritan government, and then during the Antinomian Controversy (Antinomian = "against the laws") when Anne Hutchinson, John Wheelwright, and Thomas Hooker charged Winthrop and the government with anti-biblical views and policies in establishing a community which based their hope of salvation of works instead of God's grace.

The Puritans believed in predestination – that God had chosen the elect who would be 'saved' and there was nothing anyone could do themselves to merit salvation – but also believed that one should act as though one were a member of the elect and one aspect of this was achieving financial success and stability through hard work. Hutchinson and the others had no objection to such work but did not equate one's activities with the hope of salvation. Winthrop eventually banished them all, which resulted in the colonization of Rhode Island by Williams, Hutchinson, and Wheelwright and of Connecticut by Hooker.

Indian Policy & Pequot War

Winthrop's view of the Native Americans was that they were not only in dire need of salvation but had spiritually sent the Puritans a plea for help in this. He believed it was the Puritans' responsibility to 'civilize' and Christianize the natives of North America. Winthrop believed that God had paved the way for this by sending disease some 30 years before his arrival which had killed off so many natives that it made English settlement easier. He also noted that, since the natives did not bother to mark off borders of their lands and did not seem to be making much use of them, those which had no native settlements on them were free to be taken by colonists. Between 1630-1640 CE, 20,000 such colonists would arrive in Massachusetts and would require more and more land which Winthrop said they were welcome to.

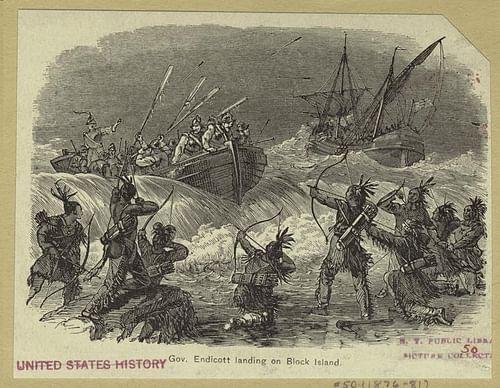

Although Winthrop is frequently blamed for the Pequot War, and certainly did have a hand in causing the problems, he was not even governor at the time the conflict started. Sir Henry Vane (l. 1613-1662 CE) was governor in 1636 CE and he sent Endicott to meet with the Niantic (tributaries of the Pequot). He did not, however, authorize violence or the burning of the villages and it was actually Endicott who was responsible for starting the war. A trader named John Stone was allegedly killed by the Niantic tribe in 1634 CE in reprisal for Stone's murder of a Niantic chief, and then, two years later, another trader named John Oldham was killed near Block Island, inhabited by the Niantic.

Vane approved the call for reparations for the killings which included a significant amount of wampum (considered quite valuable), handing over the Native Americans responsible for the killings, and a number of children of the Pequots as hostages to be held to guarantee future compliance in trade and commerce. When these demands were refused, Endicott – who, again, had not been authorized to initiate hostilities – burned Niantic and Pequot villages and killed a number of the natives.

Winthrop was governor again in 1637 CE, however, when Pequot raids on English settlements finally led to the Mystic Massacre of 26 May 1637 CE in which over 700 Pequots were murdered - many women and children - when colonists set their fortified village on fire and shot those trying to escape. Scholar David J. Silverman notes Winthrop's response to this as "the Massachusetts Bay Colony memorialized the victory by declaring a public day of thanksgiving after its soldiers returned home safely" (224). This proclamation, often wrongly attributed to William Bradford of Plymouth Colony, has become a focal point for Native American protests against Thanksgiving Day in the United States annually. The Pequots who survived the massacre were sold into slavery for life either in the region - as slaves to the Mohegan, Narragansett, and English - or in Bermuda and the West Indies.

Conclusion

Winthrop's wife Margaret died in 1647 CE, and he married his fourth wife, Martha Rainsborough, later that same year. He had served as governor of the colony for almost 20 years when he died of natural causes on 26 March 1649 CE. He was buried with honors in the cemetery which became King's Chapel Burying Ground in the city of Boston.

Although it is often claimed that the Puritans colonized New England seeking, and establishing, religious freedom, this freedom actually applied only to themselves; they had little tolerance for the religious beliefs of others. Winthrop makes this clear in his A Little Speech on Liberty, delivered after a challenge to his authority in 1645 CE. He claims that natural liberty is one's private concern but is subordinate to civil liberty which is maintained by divine will and exemplified by the government of the colony he had established. God himself set magistrates over the people to help restrain their desire to express natural liberty and conform to civil liberty. This concept, in modified form, continues to inform the policies of the United States of America.

Winthrop's other written works would also influence the development of United States' policy and vision of itself, becoming especially popular in the 20th century CE when his vision of the colony as a 'city on a hill' was applied to the United States at large first by President John F. Kennedy (served 1961-1963 CE) and then by President Ronald Reagan (served 1981-1989 CE). Long before their time, however, Winthrop's vision had come to inform the development and self-image of the new nation and encourage the belief in North America, and then the United States, as a land especially blessed by God which offered everyone the opportunity to realize their dreams.