Massasoit (l. c. 1581-1661) was the sachem (chief) of the Wampanoag Confederacy of modern-day New England, USA. Massasoit (also given as Massasoyt) is a title meaning Great Sachem; his given name was Ousamequin of the Pokanoket tribe of modern-day Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

He is best known for his interaction with the pilgrims of the Plymouth Colony and the peace treaty he signed with them in March 1621 which, though sometimes strained, would be honored by both sides until after Massasoit's death and King Philip's War (1675-1678), waged between the English settlers and a coalition of Native Americans under Massasoit's second son, Metacom (also known as King Philip, l. 1638-1676).

He is known through the primary documents of the chroniclers of the Plymouth Colony, the second governor William Bradford (l. 1590-1657) and the third governor Edward Winslow (l. 1595-1655):

- Mourt's Relation: A Journal of the Plymouth Plantation (Bradford and Winslow, 1622)

- Good News from New England (Winslow, 1624)

- Of Plymouth Plantation (Bradford, written 1630-1651, published 1856)

The Wampanoag Confederacy had been the most powerful military and political force in the region until the arrival of European traders in the region who brought diseases the Native Americans had no immunity against. Most of the Pokanoket and all of the Patuxet tribe died between c. 1610-1618 and Massasoit's power and prestige suffered. By the time the pilgrims arrived in 1620, Massasoit was paying tribute to the now more powerful Narragansett tribe and, hoping to restore his former stature, entered into the peace treaty with Plymouth Colony as his ally.

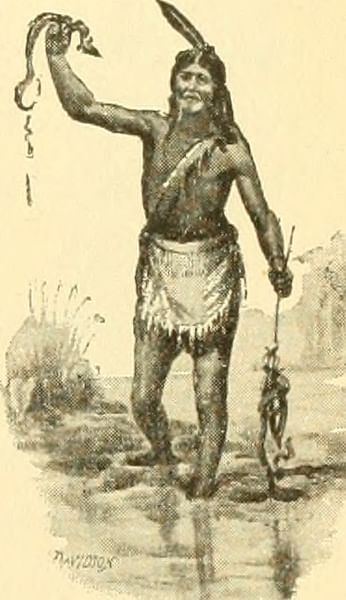

He first sent the Abenaki chief Samoset (also given as Somerset, l. c. 1590-1653) to meet with the colonists and determine whether they were friendly and, having heard his report, sent him back to arrange negotiations with Squanto (also known as Tisquantum, l. c. 1585-1622) who, like Samoset, spoke English. After the treaty was signed, Massasoit had Squanto remain with the colonists to teach them how to cultivate crops, fish, and hunt.

In doing so, he ensured the survival of the colony, which encouraged the arrival of more English ships and further colonization. Less than 100 years after the signing of the peace treaty, his lands would be taken by the second generation of settlers and his people killed, enslaved, or pushed west onto reservations. Even so, he is celebrated by the descendants of the immigrants every November at the holiday of Thanksgiving, which is inspired by the so-called First Thanksgiving of 1621 when, according to the traditional tale, Massasoit and his warriors celebrated the harvest with their new neighbors in peace and mutual respect.

Wampanoag Confederacy & the Europeans

The Wampanoag Confederacy was a coalition of clans of the Pokanoket tribe and lesser tribes under the rule of Massasoit. The confederacy's name means “people of the first light” “People of the Dawn” or “Eastern People” as they lived along the east coast of North America and claimed to be the first to see the sun rise each day.

The people of the Wampanoag had lived in the region for thousands of years prior to the arrival of the Europeans in villages made up of homes known as wetus. These were made of saplings bent and lashed in an arch covered by bark and woven mats to form a dome with a hole in the center of the roof to let out smoke from the central fire, which was always kept burning. According to later English writers, these homes were warmer and better waterproofed than any in Europe.

As with some other Native American Nations, the Pokanoket men built the homes, hunted and fished, and defended the village against attacks by other tribes while the women planted and harvested the crops (corn, beans, and squash), and gathered wild fruits, nuts, herbs, and roots, some of which were used for medicine. They also grew tobacco which was smoked during rituals and on hunting expeditions to heighten one's senses, not recreationally.

Europeans started appearing in the region in the mid-16th century and, by the early 17th, had become a common sight. The Native Americans initially welcomed the strangers and traded with them, but this relationship changed in 1610 when one Captain Harlow kidnapped a number of the neighboring Nauset tribe to sell into slavery. Among those taken was a chief of the Nauset, Epenow, who was taken to England and displayed as a curiosity for the public. After learning English, he managed to trick his captors into bringing him back to North America by telling them of a great gold mine on his island which he could show them. Once he was off the coast of modern-day Martha's Vineyard, and his people had been informed of his plan, he leaped off the ship while his warriors covered his escape with a barrage of arrows.

Epenow told the others, including Massasoit, of his experiences and warned that the English could not be trusted. His warnings went unheeded, however, and in 1614 a Captain Hunt kidnapped a number of Patuxet, including Squanto, to sell as slaves. During approximately this same time, the diseases of the European traders and slavers began taking a toll on the Native American population, wiping out almost the entire Patuxet tribe and greatly reducing that of the Wampanoag Confederacy. By the time the Mayflower arrived, the Native American view of a European ship on the horizon had dramatically shifted from welcome toward distrust and hostility.

Arrival of the Mayflower

Up until the Mayflower's arrival, the European ships had come and gone with whatever valuables their crews could stuff into the holds. The first curious aspect of this new ship was that it arrived in November, off season, and then that it appeared the passengers meant to stay. The first evidence of this had been the report Massasoit's warriors had brought him that there were women and children among the group and the women had been seen washing their clothes by the beach. Further evidence arrived at his village of Sowams – 40 miles from the site of Plymouth – that the pilgrims were building shelters, not the temporary lean-to refuges of earlier hunters and trappers, but permanent structures.

Massasoit was unsure what to make of this but feared the worst for the future of his people as evidenced by what he later told William Bradford, through Squanto, that he had at first tried to drive them away or destroy them by convening his shamans to invoke the spirits to give him a sign and supernatural aid. According to scholar Jonathan Mack, he feared they were building a permanent settlement to take revenge on the natives for fighting back against European traders following Hunt's expedition. Mack comments on how the pilgrims' early behavior did nothing to allay Massasoit's fears:

First, they chased the small group of Nauset who'd been innocently wandering the beach at the tip of Cape Cod. Then, they ransacked graves and stole corn. Next, in December, they fired their muskets in the middle of the night toward Nauset who'd been watching them from a distance. The Nauset had done nothing to provoke the reckless discharge. This likely indicated to the natives that the English intended bloodshed. (160)

The spirits had not given Massasoit a sign, nor had they seemed to take the initiative to destroy the immigrants themselves. So, Massasoit may have reasoned, perhaps these new arrivals were intended to serve some other purpose. Squanto, who had been living with Massasoit for over a year by this time, suggested that the English could be of use to them as allies against the Narragansett, and Massasoit agreed, recognizing that the European muskets and cannon, as well as the steel knives, swords, and hatchets, would be a great advantage to him in any conflict with neighboring tribes.

He needed an envoy, however, to go to the English and find out their intentions and whether they were open to a treaty, and not trusting Squanto (who was thought to have spent too long among the Europeans), he sent Samoset. Samoset was either a visitor or a prisoner of Massasoit. The colonist Thomas Morton (l. c. 1579-1647), who helped found the colony of Merrymount near Plymouth, claims in his New English Canaan (published c. 1637) that Samoset was a prisoner who was offered his freedom in exchange for accepting the mission. Instead of invoking the spirits to destroy the colonists, Massasoit would try making friends with them since it was clear they were not going anywhere.

He sent Samoset to the colony in March 1621 and was obviously unaware of how many of them had died since they had landed. It is possible that the spirits he had called upon were doing their work, just not quickly enough for him. Mack comments:

Ironically, had Massasoit waited longer, he'd likely have concluded that the powwows were successful for, without his intervention that began with his use of Samoset, the English colonists most probably would have perished before the first anniversary of their landing at Cape Cod. (162)

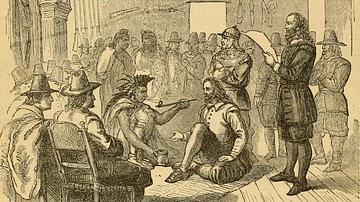

The Peace Treaty & First Thanksgiving

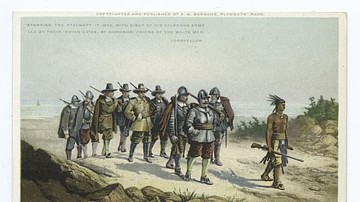

According to Bradford and Winslow, Samoset walked boldly into the settlement on 16 March 1621 and welcomed the colonists in English. They spent the day talking with him, and shortly after, he returned with Squanto, and the two of them introduced the colonists to Massasoit. A treaty was signed between Massasoit and the first governor of the colony, John Carver (l. 1584-1621) on 22 March 1621, promising mutual aid, defense against enemies, and peaceful relations between both parties. Afterwards, Massasoit ordered Squanto to remain with the pilgrims and teach them how to survive.

Squanto taught them how to cultivate the land, fish, and hunt, and acted as their interpreter in trade relations with the other Native Americans of the region. In time, Massasoit sent his right-hand man, the greatest warrior of his tribe, Hobbamock (d. c. 1643) to watch over Squanto. Hobbamock brought his family with him and became friends with Captain Myles Standish (l. c. 1584-1656), further bonding the Wampanoag to the colonists.

Whatever misgivings Massasoit had about Squanto, the latter did the job required of him completely. By mid-summer of 1621, the colony was thriving and the houses had been completed along the main street. In the fall of that year, Bradford and Winslow relate, the settlement harvested a good crop and held a feast to celebrate. According to the traditional tale, the pilgrims invited their Native American neighbors to this celebration to thank them for their help, the Native Americans brought food to share, and everyone enjoyed a time of fellowship. Actually, there is little in the primary documents that supports this vision.

The story of the First Thanksgiving is told fully in Mourt's Relation and given briefly in Of Plymouth Plantation. Mourt's Relation only says the colonists had brought in a good harvest and hunting had gone well so they celebrated with “recreation” by firing off their muskets and then “many of the Indians coming among us, and among the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted” (82). Bradford and Winslow both note how the Native Americans regularly came to the colony uninvited for trade, and it is probable that Massasoit and his men were on such a mission or perhaps were hunting when they heard the musket fire and, in accordance with the treaty, came to see if the colonists needed help.

When they saw the colonists did not have enough food to feed everyone, they left and returned with five deer, but there is nothing to suggest they were invited while, based on earlier reports of Native American visits, plenty to suggest the pilgrims just did not know how to ask them to leave without insulting them. This is not to say that there was no genuine affection between the two groups, however, nor that they did not celebrate the harvest warmly together, as both Bradford and Winslow note that relations between the colonists and Massasoit's people had moved beyond the purely utilitarian to actual friendship and mutual respect by this time.

Conflict Over Squanto

This relationship, and their treaty, was strained a few months later, however, in 1622, when it was discovered that Squanto had been working to undermine Massasoit's authority and supplant him as chief. He had been entrusted to travel to various villages delivering messages and acting as the colonists' interpreter in trade and had told the lesser chiefs how the settlers kept the plague in barrels beneath their houses and could loose it at will on whomever they pleased. In exchange for gifts, Squanto told them, he would put in a good word with his English friends and protect them.

Having built up a support base among the Wampanoag, he then devised a plan to have the colonists attack Massasoit, sending one of his people to Bradford with the false report that Massasoit was about to attack them. Hobbamock refuted the lie, and his wife was sent to Massasoit's village to see if there were any signs of preparation for war.

When she reported back that there were none, Squanto was chastised by Bradford, but nothing else was done. When Massasoit heard of Squanto's treachery, he demanded that Bradford hand him over for execution, but this was refused because Squanto was too valuable to the colony. The problem resolved itself when Squanto died shortly afterwards of fever or, according to some scholars, from poison administered secretly by Massasoit's agents.

Winslow Saves Massasoit

This event did not break the treaty, but Massasoit's relationship with the colony cooled. This dynamic would change, however, in March 1623 when Massasoit fell ill and word reached the colony that he was near death. Edward Winslow traveled to the village to pay his last respects in the company of Hobbamock. Winslow later reported how Hobbamock was nearly distraught with grief and eulogized his chief with the greatest praise:

Whilst I lived, I should never see his like amongst the Indians…he was no liar, he was not bloody and cruel like other Indians; In anger and passion he was soon reclaimed, easy to be reconciled towards such as had offended him, ruled by reason in such measure, as he would not scorn the advice of mean men, and that he governed his men better with few strokes than others did with many; truly loving where he loved. (Good News from New England, 80)

When they arrived at the village, Massasoit was being tended by his wives and shamans and seemed close to death, but Winslow, through the use of Native American medicine and his own knowledge of healing, saved Massasoit's life and then tended to others who were also sick. When Massasoit had recovered, he told Winslow of a plot by neighboring tribes to attack the settlement at Wessagussett and then Plymouth. Although this turned out to be a rumor and resulted in the unnecessary killing of some Native Americans, Massasoit had clearly put the Squanto episode behind him. He would continue to assist the colony until his death, from natural causes, but the 1621 treaty would not last even a year from his passing.

Conclusion

Massasoit had five children and was succeeded by his eldest son Wamsutta (l. c. 1634-1662), also known by the name Alexander Pokanoket, given him (at his request) by the citizens of Plymouth. At this time (1662), Josiah Winslow (l. c. 1628-1680), son of Edward, was assistant governor of Plymouth Colony, served at court, and had succeeded Myles Standish as commander of the militia. In this capacity, he was called on to investigate a complaint by the colonists that Wamsutta was not dealing fairly with them in land sales.

The fur trade was suffering due to the depletion of resources, and Wamsutta was now selling off Wampanoag land to make up for the loss. Colonists claimed he was overcharging them, and Winslow had the chief summoned to Plymouth to be questioned. Shortly after this, Wamsutta died, and his younger brother Metacom claimed he had been poisoned by Winslow or others at the court.

Metacom, also known as King Philip, then became chief of the Wampanoag and negotiated new treaties with Josiah Winslow and others to protect his people's land, but these treaties were never honored by the English colonists. When Metacom felt he had run out of options, he formed a coalition of Native Americans and launched the conflict known as King Philip's War. Between 1675-1678, most of the settlements of New England were attacked, and in retaliation, the colonists burned Wampanoag villages. Thousands died on both sides, and even after Metacom was killed in 1676, hostilities continued.

The colonists finally triumphed in 1678 after a number of tribes had sued for peace while others, from the beginning, had fought on their side believing their God was more powerful than their own and there was no way to defeat them. The people of the Wampanoag Confederacy and their allies were then either executed, enslaved, or driven from their traditional lands onto reservations further west. King Philip's War would afterwards define European-Native American relations, and the original treaty signed between Carver and Massasoit was forgotten and survived only as a historical artifact from the early days when the immigrants and Native Americans had lived together in peace.