The Carrack (nao in Spanish, nau in Portuguese, and nef in French) was a type of large sailing vessel used for exploration, to carry cargo and as a warship in the 15th and 16th centuries. Famous carracks include the Santa Maria of Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) and the Victoria, which completed the first circumnavigation of the globe in 1522.

Carracks usually carried three masts with a mix of square and lateen (triangular) sails. They could withstand rough seas and carry hundreds of tons of cargo from one continent to another making them the vessel of choice for colonial powers throughout the Age of Exploration before they were replaced by the larger galleon.

Design

The Portuguese had designed the caravel (caravela) in the mid-15th century, a medium-sized ship with a low draught and lateen or triangular sails. The caravel was well-suited to exploration in unfamiliar waters but, with a maximum weight of 300 tons, it could not carry a great deal of cargo. A larger alternative was the carrack, again developed by the Portuguese, which could be up to 2,000 tons when fully loaded, although early versions were typically around the 100-ton mark. Carracks usually had four decks with the lower two used for cargo, the third for accommodation cabins, and the fourth for privately owned cargo (by the ship's passengers and crew). The step-up in size was made possible by the frame-built design of the hull.

The carrack was a short and not particularly fast vessel. Carracks typically had only a 2:1 ratio of length-to-beam which gave them greater stability in heavy seas, although this reduced manoeuvrability. The hulls of early carracks were of pine or oak and clinker-built (with overlapping planks), but this design was eventually superseded by the smooth carvel hull. When the European empires expanded, superior Indian teak or Brazilian hardwoods were used for carracks. Castle-like superstructures for accommodation were built high at the bow and stern. These fore and aft castles were particularly necessary for carracks acting as warships when there was a large complement of marines on board. A high and imposing aft castle was useful as a retreat of last resort if the vessel were boarded. The downside of these large superstructures was that they could make a ship top-heavy and reduced its manoeuvrability.

The three or four masts of a carrack carried a mix of square and triangular sails, perhaps 10 in total. The usual arrangement of sail was square sails on the foremast and mainmast, a lateen sail on the mizzenmast (closest to the stern), and a small square sail on the bowsprit. If there was a fourth (bonaventure) mast, it was rigged with another lateen sail. This mix allowed the ship to profit from the wind whether it be fully astern or even a headwind.

Maintenance

Carracks, like any other type of ship of the medieval and early modern periods, leaked. Pumps had to be manned, especially in heavy seas to keep the filthy waters down in the bilges of the ship at an acceptable level. For the same reason, the outside of the hulls had to be protected if they were going on lengthy sea voyages. A thick black tar mixture was applied to that part of the hull above the waterline to prevent rot. Below the waterline, hot pitch was used to coat the planks to increase the water-resistance of the wood. Then a mixture of pitch and tallow (animal fat) was smeared all over the hull to deter marine animals and especially shipworms. None of these methods was entirely efficient, and really it was only a matter of time before a ship disintegrated into rotten, worm-riddled flotsam, especially in tropical waters. If the mariners were lucky, the ship would get them home, just about.

The actions of the sea, salt spray, wind, sun, and ice all took their toll on wooden ships. Repairs were never-ending. Rigging, made from twisted flax, had to be constantly renewed and wind-tattered canvas sails repaired. At least once each voyage, and very often twice, more drastic maintenance was required. The hulls had to be periodically scraped of thousands of marine encrustations like barnacles that significantly slowed the ship down. This involved laying anchor in shallows and shifting the entire ship’s stores and cargo to one side of the vessel’s holds. Ropes were then used to tip the ship over at an angle so that the lower part of the hull was exposed and men could scrape it. When done, the whole process was repeated for the other side of the ship. This was also an opportunity to recaulk the ship, that is push an oakum filler (loose rope fibres) between the hull’s planking in order to make them as watertight as possible.

Trade & Naval Warfare

In the 16th century, the superior cargo capacity of carracks made them a common sight as they criss-crossed the oceans along trade routes from the Americas to Europe and from Europe to India and East Asia. Colonies like Portuguese Goa welcomed merchant ship carracks from all over the world as gold, spices, silk, ivory, and slaves were shipped from one ocean to another.

As naval warfare developed and tactics changed from boarding an enemy vessel to blasting it out of the water using cannons, so carracks evolved. Previously, many small cannons were carried on deck, but as these weapons became larger they had to be placed lower in the ship to prevent it capsizing. Consequently, gun ports were used, in effect, windows, which could be closed with a shutter when not in battle. A ship like the Mary Rose (see below) carried 90 cannons. This added a new danger, though: flooding the vessel. Gun ports on early carracks were as little as one metre (39 inches) above the waterline. The carrack also carried an additional arsenal of small cannons in the fore and aft castles, which could be used to fire down onto the decks of an enemy ship at close quarters or present a formidable fire at the stern. A weak spot was the carrack's bow, which could not present any artillery pieces.

From the second half of the 16th century, the carrack was gradually replaced by the larger and more seaworthy galleon, both as a merchant vessel and warship of choice. The galleon combined the best design features of vessels like the carrack and caravel, had much lower forecastles, was faster, more manoeuvrable, and could carry many more heavy cannons. The Spanish galleon was bigger still and carried even more cannons as firing broadsides and blasting fortifications on land became an integral part of naval warfare.

Famous Carracks

The Santa Maria

The Genoese explorer Christopher Columbus set sail for the New World in 1492, although he was actually looking for a maritime route to Asia and direct access to the lucrative spice trade of the East. His fleet of three ships was composed of two caravels, the Niña (‘The Girl’) and Pinta (‘The Painted One’), and his flagship, the carrack Santa Maria. The famous carrack was not young, having been launched in Pontevedra in Galicia, northern Spain in 1460. The ship was around 19 metres (62 ft) in length and weighed around 108 tons, tiny for a voyage into the unknown. The Santa Maria had three masts and a bowsprit which collectively carried five sails. The ship was the slowest of the trio but the largest with a crew of around 40 men, double that of the caravels. Columbus ultimately landed on an island in the Bahamas, and not the continent of Asia or America, but he had shown the way across the Atlantic for countless ships to follow in his wake.

The São Gabriel & São Rafael

The Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama (c. 1469-1524) sailed around the Cape of Good Hope and made the first maritime voyage from Europe to India in 1497-9. Two of his four ships were carracks: the São Gabriel and São Rafael. Purpose-built for the expedition, da Gama himself commanded the São Gabriel.

The Victoria

The Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan (c. 1480-1521) set off with a fleet of five ships to find a maritime route to Asia and circumnavigate the globe from east to west. No expense was spared and the fleet included four carracks: San Antonio (120 tons), Trinidad (100 tons and Magellan’s flagship), Concepción (90 tons) and Victoria (85 tons). The Victoria was launched in Gipzkoa in Spain in 1519. The ship measured 18-21 metres in length (59-69 ft) and had a carvel-planked hull. Magellan’s fleet was the first to round Cape Horn in South America and the first European ships to cross the Pacific Ocean. Magellan was killed in the Philippines, but the Victoria returned to Spain in 1522. The carrack had been away from home for three years and sailed over 60,000 miles. It was the only ship of Magellan’s fleet which returned to Europe.

The Mary Rose

The Mary Rose was the flagship of the Royal Navy built by Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547). The carrack warship was built in Portsmouth and launched in 1511. The ship had a keel length of 32 metres (105 ft) and was originally 500-600 tons but after a refit was nearer 800 tons (without cargo). After serving in the Battle of St Mathieu against the French in August 1512 and acting as a troopship in the Scottish campaign of 1513, the ship infamously sank in the Solent off the south coast of England on 19 July 1545 during the Anglo-French war of 1542-46. The disaster was probably due to water entering its open gun ports as Mary Rose made a sharp turn. Almost everyone on board the Mary Rose drowned. The carrack's crew consisted of around 200 seamen, 185 marines, 30 gunners, and a good number of archers. The wreck was raised in 1982 and is now preserved and on public display in the Portsmouth Historic Dockyard.

The Madre de Deus

The Madre de Deus was a massive Portuguese carrack, which was captured by English privateers in the Azores in 1592. The high seas robbery was masterminded by Sir Walter Raleigh (c. 1552-1618), although he was not present. Rather, the attack fleet was led by Martin Frobisher (c. 1535-1594). With a crew of 700 men and a hull bristling with 32 cannons, the Madre de Deus was a 1450-ton giant with a keel length of 30.5 metres (100 ft) and a beam of 14 metres (31 ft). The fleet of at least seven English ships was faster and more manoeuvrable, and if they could keep in front of the Portuguese vessel where there were hardly any cannons, the attack had a good chance of success. After a brave resistance lasting several hours, the Portuguese eventually surrendered.

The captured ship was packed full with 500 tons of precious goods from East Asia. There were spices, perfumes, pearls, jewels, rolls of silk, fine carpets, gold, and silver stored in the ship's seven decks. It was the single richest prize ever taken by privateers of Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603) and was sailed triumphantly into Dartmouth harbour. The English queen was delighted with her prize, and she received a handsome £80,000 return on her £3,000 original investment in the privateering project.

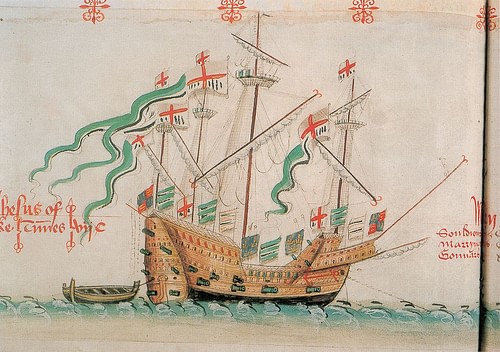

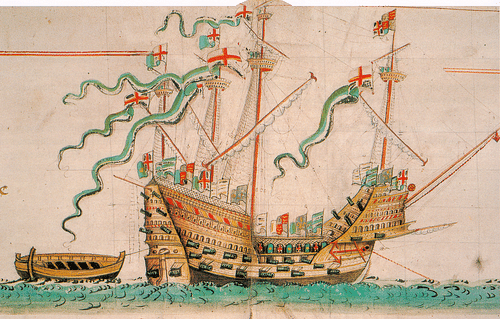

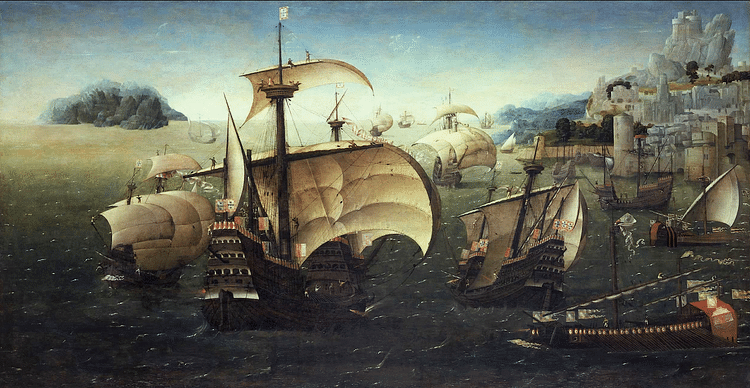

Representations of Carracks

Carracks appeared in all manner of places besides on the sea. These ships were such an important part of maritime culture empires that they appeared in countless paintings, as illustrations in books, as part of beautifully illustrated manuscripts, and on coats of arms. Perhaps the most famous book, packed full of depictions of carracks and other vessels of the period sorted by expedition fleets, is the mid-16th century Livro das Armadas now in the Academy of Sciences in Lisbon. Another interesting catalogue of ships is the 1616 Livro das Traças de Carpinteria, which is, in effect, a construction manual and so shows illustrations of specific parts of ships in detail.

Carracks feature prominently in 16th- and 17th-century maps. For example, the celebrated giant map of the world drawn by Juan de la Cosa (c. 1450-1510) in 1500 shows carracks on many of the coastlines. The map is now in the National Naval Museum of Madrid.

The Mary Rose is famously portrayed on the Anthony Roll. These three rolls of vellum, now in the British Library in London, carried illustrations of 58 English ships, and, created by Anthony Anthony, they were presented to Henry VIII sometime in the early 1540s. Finally, carracks were a popular subject for oil painters from the 16th century onwards. The carrack sterns were often positively bristling with cannons and so artists usually favoured capturing the ships from this most dramatic of angles.