Trapezus (Greek: Τραπεζοῦς) or Trebizond was a Greek city on the southern shore of the Black Sea, modern Trabzon. According to the Christian author Eusebius, writing more than a millennium after the event, Trapezus was founded in 756 BCE, in the country that was called Colchis. Its first settlers were from Sinope (Xenophon, Anabasis, 4.8), a Greek city on the southern shore of the Black Sea, about 400 kilometers to the west. Because this city was a daughter of Miletus, which in turn was believed to be a colony of Athens, the Trapezian scholar Cardinal Bessarion would still boast to be an Athenian in Renaissance times.

If we are to believe Pausanias (Guide to Greece, 8.27.6), there was a second wave of immigrants from the Peloponnese, after the city had been destroyed by the Cimmerians in c. 630 BCE. This story may be a late invention, only meant to explain why there was a town named Trapezus in Arcadia too; on the other hand, this may have been the city's real founding moment, the first one being just a legend.

However this may be, the city was a very important port and appears to have played a pivotal role in trade between Greece and the Iron Age civilizations of Anatolia, especially Urartu. Many metal artifacts must have been shipped to Greece from Trapezus, which may explain why so many pieces of Greek art in the Oriental Style resemble Urartian objects.

The city was not to become wealthy because of its agricultural produce. Its acropolis is on an outcrop of the Paryadres, a mountain range parallel to the coastline; there's almost no flat land that might have been suitable for agriculture. However, there's a good port (the only one east of Amisus), and there are several roads across the Paryadres mountains.

The mountain slopes were covered with forests, allowing the Trapezians to build ships and produce wine and honey. Tuna fish is mentioned by Strabo, a geographer from nearby Amasia (Geography, 7.6.2). The Chalybes, as the Greeks called the mountain tribes, were well-known for producing iron ore. Later, we hear about other tribes living in the mountains, the Mossynoeci and Drilae.

Persians, Greeks, & Mercenaries

Persian influence must have been real in the late sixth century BCE, at least theoretically, because the southern shore of the Black Sea is mentioned by Herodotus of Halicarnassus as part of the third and thirteenth tax districts of the Achaemenid Empire. Later, the city may have been one of the towns of the Delian League.

In the early spring of 400 BCE, the remains of the army of the Persian usurper Cyrus the Younger, which had returned from their ill-fated expedition against Artaxerxes II Mnemon, arrived in Trapezus; the survivors sacrificed to the Greek gods. One of its commanders, Xenophon, offers some information about the city in his Anabasis , which he calls "populous" (4.8.22). The army supported the Trapezians, who had a quarrel with both the Drilae (5.2) and the Mossynoeci (5.4).

Several years later, in 368/367 BCE, people from Arcadian Trapezus who were not willing to move to newly-founded Megalopolis, migrated to Pontic Trapezus (Pausanias, Guide to Greece, 8.2.7). Another generation later, the city was allotted to Eumenes of Cardia, one of the successors of Alexander the Great (Arrian, Events after Alexander).

Roman Trapezus

In the first half of the first century BCE, the city was part of the Pontic kingdom of Mithradates VI, and its port was used by the fleet of Pontus. Nevertheless, it soon joined the Romans, and was offered by Pompey the Great to King Deiotares of Galatia. In the first century CE, the Romans later recognized Trapezus as a free city (Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 6.4). According to later legends, Saint Andrew was to explain Christianity to the Trapezians.

The conflict between Rome and the Parthians was mainly fought in Syria, but the strategic importance of Armenia made the Romans occupy the greater part of Anatolia. This made Trapezus an important city, because it was one of the few ports on the northern coast of this area. It was a crucial node between the limes (border zones) along the Rhine and the limes along the Euphrates.

During the reign of Nero (53-68 CE), the city was in use as a supply base for the Armenian campaign of Corbulo (Tacitus, Annals, 13.39); its strategic importance was, in the Year of the Four Emperors, recognized by Anicetus, one of the supporters of Vitellius (Tacitus, Histories, 3.47); and Vespasian developed the area, building a road across the Zigana Pass, which was defended by the legionary fortress at Satala, base of XVI Flavia and, later, XV Apollinaris. Finally, it was Hadrian who improved the port (Arrian, Periplus). The remains have been identified.

In the crisis of 193 CE, Trapezus, now a flourishing city, supported Pescennius Niger, and was consequently punished by the victor of the civil war, Septimius Severus. The city remained prosperous and attracted attacks by the Visigoths (in 257 CE) and Sasanian Persians (in 258 CE) during the reign of Valerian. A double wall and a garrison of 10,000 additional soldiers were insufficient to prevent its capture, according to Zosimus.

Trapezus in Late Antiquity

The city walls were repaired by Diocletian (284-305 CE), and Trapezus received a new garrison: the First Legion Pontica. This appears to have happened in the first decade of Diocletian's rule. The unit is mentioned in a dedication (CIL, 3, 6746) that can be dated to 297-305 CE and was still in this town when the Notitia Dignitatum was composed, an early 5th century CE list of Roman magistracies and military units.

The reign of Diocletian and Galerius, his caesar, witnessed ferocious persecutions of the Christians. In Trapezus, Eugenius, Canidius, Valerian, and Aquila were tortured to death. About the latter, we know that he destroyed a statue of Mithras on a hill overlooking the city, and that he became the patron saint of Trapezus. Another sanctuary of Mithras was to serve as crypt for the church of Panaghia Theoskepastos. The driving force of the Christian fight against the cult of Mithras had been Gregory Thaumaturgus from nearby Neocaesarea.

During the reign of Constantine, the city belonged to the Diocese Oriens. It was represented by its bishop, Domnus, during the Council of Nicaea. We know that Prince Hannibalian founded a church dedicated to the Virgin; not much later, Ammianus Marcellinus calls Trapezus "a celebrated city" (Roman History, 22.8.16). Perhaps the Soumela Monastery, south of the city, was built in this age, although it may a bit younger.

During the reign of Justinian, the aqueduct was improved (Procopius, Buildings, 3.7) and named after the martyr Eugenius. An inscription proves that the walls were repaired as well. There were also repairs to the Soumela Monastery.

Byzantine Trapezus

Under the Byzantine emperors, Trapezus suffered decline, although it was one of the places where Muslim merchants arrived to do business with Byzantine traders. From 824 CE, it was the capital of the theme (military district) of Chaldia.

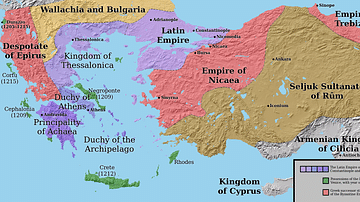

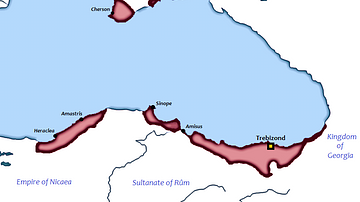

After the knights of the Fourth Crusade had captured Constantinople, however, the imperial dynasty of Byzantium, the Comnenes, escaped to Trapezus, making it the capital of the Empire of Trebizond. It surrendered to the Ottomans in 1461 CE, marking the end of the Byzantine Empire.

Little remains of ancient and medieval Trapezus, except for the ruin of the palace of the Comnenes and the medieval church of Hagia Sophia, the answer of Trebizond to the church with the same name in Constantinople. After the Ottoman take-over, Trapezian artists and scholars like Cardinal Bessarion traveled to Italy, taking with them precious manuscripts. The ancient city was, in this way, an important connection between the ancient culture, as continued in Byzantine art and scholarship, and the European Renaissance.