Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, constructed 532-537, continues to be revered as one of the most important structures in the world. Hagia Sophia (Greek Ἁγία Σοφία, for 'Holy Wisdom') was designed to be the major basilica of the Byzantine Empire and held the record for the largest dome in the world until the Duomo was built in Florence in the 15th century. Additionally, Hagia Sophia became more important with time as subsequent architects became inspired by the dome when building later churches and mosques.

Construction & Design

After the Nika Riots of 532 destroyed the previous basilica in Constantinople, Emperor Justinian (r. 527-565) sought to create the greatest basilica in the Roman Empire. He charged two architects, Anthemios of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus to create a structure worthy of the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. The architects, who were primarily mathematicians, made use of new architectural concepts in order to build exactly what the Byzantine emperor wanted. In order to create the largest interior space possible, they designed an enormous central dome and supported it using a revolutionary construction method called pendentives. Hagia Sophia makes use of four triangular pendentives which allow for the weight of the circular dome to transition to a square supporting superstructure below without massive pillars or columns interrupting the internal space.

The dimensions of the extant structure show Hagia Sophia's near square shape: length 269 feet (81 m), width 240 feet (73 m). The cupola of the current dome hovers 180 feet (55 m) above the mosaic floor. The structure and first dome, which partially collapsed in 557, were first completed in 537. The second dome, designed with structural ribs and a greater arc than the previous dome, was designed by the nephew of one of the original architects, Isidore the Younger.

Isidore the Younger was faced with fixing several issues that had caused the original dome to collapse. First, during the original construction, the bricklayers had heedlessly applied more mortar than brick. Additionally, in the rush to complete the original dome, they had not waited for a layer of mortar to set before applying the next level of bricks. This caused structural problems that were only exacerbated by a dome that was too shallow. When a dome's arc is round enough, the weight and force of the structure descend down into the supporting piers. However, the original dome's arc was too shallow, thereby, pushing outward and forcing the already weakened walls to give. To fix these problems Isidore the Younger increased the height of the dome, which increased the arc and depth, and added 40 ribs to provide support. Before these improvements, however, he was forced to rebuild much of the original walls and semi-domes in order to make the new dome last longer than the first.

Descriptions of the Dome

This history of the two generations of architects and two separate domes is known through both Byzantine authors and through 20th-century architectural surveys. The magnificence of Hagia Sophia is recorded throughout the centuries as shown in this description by a 9th-century patriarch of Constantinople named Photios:

It is as if one were stepping into heaven itself with no one standing in the way at any point; one is illuminated and struck by the various beauties that shine forth like stars all around. Then everything else seems to be in ecstasy and the church itself seems to whirl around.

In the 20th century, many architectural engineers were fascinated by the scale of Hagia Sophia and wanted to know how it was designed, executed, and built. Robert Van Nice, working for Dumbarton Oaks, was the first Westerner given access to the newly secularized Hagia Sophia in the 1930s. Van Nice's structural analysis was subsequently published in the 1960s.

The aesthetic qualities of a geometric design are what most concern the 20th-century work on Hagia Sophia. Due to the association of beauty, harmony, and mathematics, an objective description of Hagia Sophia reveals a certain beauty concerning its design. This is true of many structures built in ancient Rome and Late Antique Constantinople, for example. As Anthony Cutler wrote in the 1950s, “the essential and manifest characteristic of early Byzantine architecture, the disciplinary relationship between mathematics and structural mechanics.” For example, the design of Hagia Sophia makes use of pendentives as an aesthetic choice that creates harmony and symmetry. According to Cutler, the pendentive is a geometric solution to an engineering problem that simultaneously creates an aesthetic effect. This interplay of geometry and beauty characterizes Byzantine understanding and engineering genius. The dome's design symbolizes something immense and beautiful.

Interior Decoration

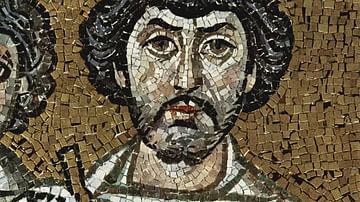

The interior of Hagia Sophia was innovative in its decoration as well. The interior is lined with enormous marble slabs which may have been chosen and designed to imitate moving water. The central dome is floated on a ring of windows and supported by two semi-domes and two arched openings. This creates an enormous uninterrupted nave. The pendentives were covered with enormous mosaics of six-winged angels called hexapterygon. The two arched openings are supported by massive porphyry columns which descend all the way to the floor.

Originally the nave was lined with intricate Byzantine mosaics which portrayed scenes and people from the gospels. After the Ottoman conquest, many of these Christian mosaics were covered over with Islamic calligraphy and only rediscovered in the 20th century after the secularization of Turkey (when it was converted into Hagia Sophia Museum in 1935). This includes the mosaic on the main dome which was probably a Christ Pantocrator (All-Powerful), which spanned the whole ceiling and is now covered by remarkable gold calligraphy. On the floor of the nave, there is the Omphalion (navel of the earth), a large circular marble slab which is where the Roman and Byzantine emperors were coronated. One of the final additions the Ottoman sultans made to finalize the transition from Christian church to Islamic mosque was the inclusion of eight massive medallions hung on columns in the nave with Arabic calligraphy inscribed upon them with the names of Allah, the Prophet Muhammed, the first four caliphs of the Rashidun Caliphate, and the Prophet's two grandsons. The Ottomans also added a mihrab, a minbar, and four enormous minarets in order to complete the transition to an imperial mosque.

Influence on Later Architects

The daring genius of the architects of the 6th century made use of pendentives and tympana on a scale not previously envisioned. Their use of innovative techniques includes a brick aggregate that is lighter and more plastic than solid stone or concrete which allowed for the dome to create an internal space not surpassed in Western Europe for 1,000 years. Additionally, after the fall of Constantinople: 1453, the genius of Hagia Sophia's architects continued to dominate the conquering Ottoman Empire who made use of the designs for their mosques. The Ottomans conquered the city, but the artistic culture of the Byzantines, in a way, conquered the Ottomans. Hagia Sophia, under orders from Mehmed II the Conqueror, was converted into a mosque within days of the conquest preserving the legacy of Byzantine architecture in a new form and era.

Later Ottoman mosques were equally influenced by Hagia Sophia. The Blue Mosque, for example, preserves a layout inspired by Hagia Sophia that builds upon its innovations of pendentives and semi-domes to create internal space. Additionally, Islam's use of geometric shapes and patterns, as opposed to Orthodox Christian imagery used in icons, also finds continuity in Greco-Roman-Byzantine's use of geometry in sacred architecture as mentioned previously. In fact, the very same Sinan who built the Suleymaniye also worked to repair the millennium-old Hagia Sophia during the reign of Selim II.

In addition to the impact Hagia Sophia has had on Ottoman architecture, it also inspired and influenced Greek and Russian Orthodox architecture for centuries. Victoria Hammond, author of Visions of Heaven: The Dome in European Architecture, in particular, suggests that Russian Orthodox basilicas in Moscow and Kiev were directly inspired by early Muscovite contact with Constantinople in the 10th century.

Despite the finality of the transition from Byzantine to Ottoman with the removal of the Christian icons, Hagia Sophia continued in its function as a sacred space as a mosque called Aya Sofya. Even today Hagia Sophia maintains its position as a sacred space, despite its current position as a secular museum, because of what it inspires, what it symbolizes, and the effects it creates on visitors. The original architects' vision of a structure as the synthesis of religion and mathematics determines the impact it has on the viewer. And in return, it is the impact that Hagia Sophia has on the eye which determines its lasting importance and beauty. Its scale, symbolism, and transcendence of the construction material demonstrate what Justinian said when it was first completed in 537, “O, Solomon, I have outdone thee!”