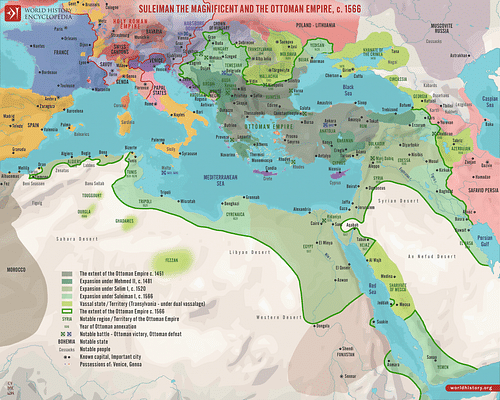

Suleiman the Magnificent (aka Süleyman I or Suleiman I, r. 1520-1566) was the tenth and longest-reigning sultan of the Ottoman Empire. Hailed as a skilled military commander, a just ruler, and a divinely anointed monarch during his lifetime, his realm extended from Hungary to Iran, and from Crimea to North Africa and the Indian Ocean. As he engaged in bitter rivalries with the Catholic Habsburgs and the Shiite Safavids, he presided over a multilingual and multireligious empire that promised peace and prosperity to its subjects.

Early Life

Suleiman was born in 1494 or 1495 in Trabzon, on the Black Sea coast. His father Selim served there as provincial governor, and his mother Hafsa was a concubine in his father's harem. Suleiman grew up in a multiethnic, multireligious town. While he led a privileged life, he also lived in a district where contagious diseases and food scarcity were rampant, even for the upper classes. He received an elite education under the supervision of tutors, including a strong poetic formation. He also received martial training, and he remained an avid and skilled horseman and hunter to the end of his life.

Suleiman's adolescence and youth were spent under the shadow of his father Selim, a violent, overbearing man. As he reached puberty, like other Ottoman princes, he became eligible for service as district governor. Following a tense negotiation between his father and the palace, he was appointed to Caffa, in the Crimean Peninsula. His father Selim subsequently used Caffa as a center of operations in his bid to replace the ruling sultan, Bayezid II (r. 1481-1512). After becoming sultan in 1512, Selim I (r. 1512-1520) killed his brothers and nephews, stopped the advance of the millenarian Safavid movement into the Ottoman territories by defeating its leader Ismail in 1514, and occupied the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt in 1516-17.

After his father Selim came to the throne, Suleiman was given another district governorship in western Anatolia. The resources at his disposal increased considerably, as he came to preside over a crowded household as the heir apparent. During Selim's campaigns, he acted as his father's proxy by relocating to Edirne, the gateway to the Balkan provinces, where he became acquainted with the management of the empire at the highest level.

These were the years during which Suleiman began stepping into the limelight of Ottoman political and cultural life. He began writing poetry, a sign of intellectual maturity as well cultural refinement. He also began having children with his concubines, securing the reproduction of the Ottoman dynasty, and transitioning from adolescence into fatherhood.

Suleiman's father Selim's control of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, and his adamant struggle against non-Sunni Islam, gave a particular flavor to Ottoman religiopolitical identity in the years preceding Suleiman's arrival on the throne. Moreover, Selim's conquests to the east and south allowed the Ottomans to benefit from global commercial networks that extended overland from China to the west, and over the sea from the eastern Mediterranean and the Red Sea into the Indian Ocean. A truly global empire, with a large territory, a stake over regional and global commerce, and a sophisticated cultural identity, thus began to emerge under Selim. Suleiman inherited this imperial geography and mindset from his father and took it farther than ever imagined by any Ottoman ruler before him.

Rise to Power & Military Conquest

Suleiman came to the Ottoman throne in the fall of 1520, upon his father's death. In the absence of any nephews, uncles, or brothers who might contest his accession, his rise was at first sight effortless. That said, he had crucial disadvantages he had to overcome. He was not known to the large sections of the ruling elite, had not commanded any forces on the battlefield, and did not have his own clique within the ruling circles.

His first step was to promote himself as a just ruler, a virtue his father was not known for. His second step was to direct the Ottoman armies towards targets his father had ignored. He took Belgrade from the Hungarians in 1521; he captured Rhodes from the Knights Hospitaller in 1522; and he defeated Louis II of Hungary (r. 1516-1526) at the Battle of Mohács in 1526, thus ushering in the collapse of the Kingdom of Hungary. His third step was to raise a household servant named İbrahim to the highest rank, the grand vizierate. This is also the time when he began a lifelong relationship with a concubine named Hürrem.

After 1526, Suleiman faced many powerful rivals on the European front. These were the Habsburg brothers Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria (l. 1503-1564), and Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1519-1556). As he competed with them over the control of Central Europe, Suleiman failed to take Vienna in 1529, and a large campaign he organized in 1532 produced mixed results. A costly stalemate began to emerge on the western frontiers of the Ottoman Empire. Suleiman then turned his attention to the East. A campaign against the Safavids, between 1534-36, captured large territories, including Baghdad, but failed to decisively defeat the Safavids and their supporters.

Public Image & Administration

earth.

Suleiman's challenges were not only of a military nature. He constantly searched for new ways to present himself as a mighty emperor. With the help of his longtime companion and grand vizier İbrahim, he borrowed ideas from Central Asian and Islamic cultural traditions, such as the notion of a universal ruler born under the auspicious conjunction of the stars. He also toyed with European/Christian ideas, such as the Last World Emperor. In the late 1520s and early 1530s, Suleiman increasingly presented himself as a messianic figure who would gather Islam and Christianity under a single mantle. His competition with Charles V was not only over the control of Central Europe and the Mediterranean but also over Charles' title of Holy Roman Emperor. Suleiman and his close supporters argued that Suleiman was the one and true emperor on

earth.

While Suleiman's grand vizier and close companion İbrahim was executed on Suleiman's orders in 1536, the sultan found other collaborators who helped him manage the realm, notably his son-in-law Rüstem. In the 1530s and 1540s, Ottoman military ventures became even more prominent, with large-scale campaigns against the Safavids, clashes in east-central Europe, a stronger naval presence in the Mediterranean, and engagements in the Indian Ocean.

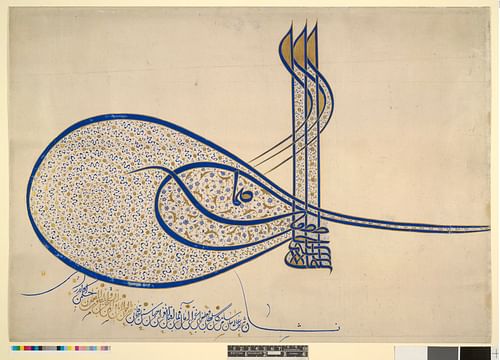

The bureaucratic apparatus was further extended to ensure the ruler's control over the resources. In addition, there were significant attempts at harmonizing the Sharia with dynastic law (kanun). There was an increasing emphasis on justice, both as a tool of empire management and as a universalist political ideal that demanded loyalty from the empire's subjects in return for peace and prosperity. Also in this period, Suleiman and Hürrem began creating their first large-scale charitable works, already mindful of their legacies.

Challenges

Starting with the early 1540s, everything around Suleiman reminded him that he was entering old age. There were grey flecks in his beard and hair. He got gout, whose debilitating pain affected him more and more despite his physicians' aggressive treatments. There were persistent, ever-growing rumors about him being replaced by one of his sons. He felt increasingly lonelier. His tutor Hayreddin, his constant companion since adolescence, died. His favorite son Mehmed succumbed to a contagious disease at the tender age of 21.

His political life was filled with frustrations as well. In his early years on the throne, he had dreamed of subjugating all his enemies and ruling over East and West with justice. After many long and costly campaigns, what he had was a stalemate on both fronts, as his Habsburg and Safavid rivals initially retreated and then regrouped. As for his allies, such as the anti-Habsburg Hungarians and the French, he thought they were weak, uncommitted, and unreliable. Suleiman became an angry man. He openly scolded foreign envoys during audiences, abandoning his usually austere demeanor. He more and more consulted a geomancer to find out whether his health would improve, whether he would be able to remain on the throne, and whether he could conduct his armies to victory.

His life became even more complicated in the 1550s. He ordered the execution of a son on the suspicion of rebellion. A few years later, another son rebelled, was defeated, escaped to Iran, and was executed there on his instructions. All along, Suleiman's health continued to worsen. Then his beloved wife Hürrem died. The empire he had expanded and the bureaucratic machinery he had helped build suffered from overextension. Social and economic problems persisted, becoming increasingly more difficult to ignore as casual or haphazard occurrences.

Art & Architecture

Once again, Suleiman rose to the challenges in front of him, and his answer was to create a self-curated legacy. He ordered the building of a major charitable complex centered around a mosque in Constantinople. He dotted the entire realm with signs of his charity and wealth, from bridges to waystations for pilgrims, from aqueducts to city walls, and from prayer houses large and small to soup kitchens.

As a lifelong reader and composer of poetry, he gathered his compositions together to leave behind his voice, perhaps the most intimate part of his legacy. He also decided to have the story of his reign written from his own perspective. The result was a lavishly illustrated history in versified Persian, called the Sulaymannama (also given as Süleymanname - "Book of Suleiman"). It described three and a half decades of Suleiman's sultanate, from his accession in 1520 to the mid-1550s. The work was composed by a court historian, calligraphed by a scribe, and decorated by artists.

Final Campaign & Death

On 1 May 1566, Suleiman left Constantinople at the head of the household troops. In old age, devastated by gout and digestive issues, he still had to personally lead his army to besiege a minor castle, to prove that he was healthy enough, powerful enough, sultan enough, to remain on the throne. In the early stages of the campaign, he continued to remain visible to his men on ceremonial occasions. By late July, however, he was too sick to ride on his horse even for short periods of time. Everything upset Suleiman. Roads turned to mud under the heavy rains, hampering the advance of the Ottoman forces. Supply chains began to break. Angry and tired, he took his frustrations out on his own men, ordering dismissals and public beatings.

By the time he arrived in front of the fortress of Szigetvár, the target of the campaign, he was exhausted. As the Ottomans laid siege to the fortress, his health continued to deteriorate. He died on the night of September 6/7, 1566, of natural causes, just before the fortress finally fell to Ottoman forces. Suleiman's corpse was washed, placed in a white shroud, and buried under his tent. Given the need for exhumation and eventual reburial in Constantinople, the corpse was preserved by being bound with wax-treated cloth strips and the application of perfumes and essences. The soldiers were not notified of the sultan's death, to prevent turmoil and rioting in the army camp. The news was shared only with a small group of confidants. Imperial decrees were issued in the name of the sultan, and physicians continued to enter his tent to create the semblance of ongoing treatment, while messengers were sent to his son Selim, the heir apparent.

A public funeral prayer for Suleiman was finally held outside Belgrade, on the way back, after his death was announced to the soldiers. His corpse was then sent to Constantinople, where another funeral prayer took place. He was buried next to the mosque he had built to his name, the Suleimaniye, near the tomb of his wife Hürrem. His worldly life thus ended. His myth, parts of it already built and circulating during his reign, began to live a life of its own.

Legacy

Already during his lifetime, Suleiman was hailed as a skilled military commander, a just ruler, and a divinely anointed monarch. For his European contemporaries, who called him the "Grand Turk," he was an awe-inspiring figure. He presided over a large household and army, and his wealth was legendary. European observers of the time also depicted Suleiman as a tyrant whose conquests dealt mortal blows to Christianity and who cruelly ordered the murder of his own children and grandchildren. A similar ambiguity was exhibited by Suleiman's rivals farther east, the Safavids of Iran. Under the dual threat of military violence and accusations of heresy from their Sunni Ottoman neighbors, the Safavids treated him with a mixture of apprehension and grudging respect.

Suleiman's image was partly based on his exploits as a military commander. He personally traveled long distances, from the plains of Central Europe to the mountainous terrain of western Iran. His fleets sailed across the Mediterranean and into the Indian Ocean, and his armies marched into the Caucasus, Yemen, Hungary, and Austria. He is also remembered today for his contributions to Ottoman bureaucratic and legal practice. Indeed, after his death, authors have given him the moniker "Kanuni", i.e. "the formulator of dynastic law", under which name he is widely known today to Turkish-speaking audiences.

In the modern period, various conservative movements espoused Suleiman as a founding father for the ideal of a universalist Muslim empire built on bureaucratic efficiency and justice. From the beginning of the Cold War in the late 1940s to the recent resurgence of new forms of political Islam, Suleiman was thus able to find a place in modern political discourses. As the global popularity of a recent Turkish-made television series, The Magnificent Century, attests, the life of Suleiman continues to fascinate audiences across a wide geography that extends from southeastern Europe, through North Africa and the Middle East, to Bangladesh and Pakistan.

Suleiman left behind a variety of legacies that continue to be debated today. Unlike many Ottoman rulers, he married a concubine from the harem and remained true to her most of his life; the level of love between them is obvious from Suleiman's poetry and Hürrem's letters. The advocacy of Sunni Islam as a political identity, next to a religious or cultural one, was another legacy that was further developed during his reign. A state-like administration was established during his reign to manage economic resources as well as legal matters across the realm. The growing emphasis on the supremacy of the law and the contractual relationship between the ruler and the ruled eventually changed the nature of the Ottoman polity.

Suleiman was contemporaries with figures similar to him, who either inherited dynastic enterprises that they subsequently expanded or built themselves. These included Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Francis I of France, and Henry VIII of England in Europe, Shah Ismail and Shah Tahmasb in Iran, Ivan IV in Russia, and Babur and Akbar in India. Like Suleiman, these figures resorted to warfare as an instrument of empire-building, while they sought to establish control over their own elites and aristocracies, with whom they competed over available resources. They all paid particular

attention to creating and maintaining a multilayered reputation as rulers, patrons, soldiers, statesmen, etc. They all sought to establish central control over religious matters during a time of intense theological debates and spiritual anxieties. They were also acutely aware of each other, and they openly competed among themselves for control of land and resources and for prestige.

A very modern form of rulership was crafted by these figures and their entourages in this period. The foundations of the modern states and bureaucracies, and of modern capitalist economies, were laid down, in the midst of the first genuine wave of globalization in human history. At the same time, Suleiman and those like him lived and worked in societies in which gender-based, racial, and religious hierarchies created conservative, male-centric social systems and political regimes. Our world today emerged from theirs, by destroying their world through the mechanism of the modern nation-state and industrial capitalism, but some of their hierarchical views, their ideas of leadership, and their politicized notions of religion are with us, still waiting to be surpassed.