Heraclius (Herakleios) was emperor of the Byzantine Empire from 610 to 641 CE. He crushed the Persian empire and returned the looted True Cross to Jerusalem, but the second half of his reign was beset by intrigues and ecclesiastical controversies which split the Christian church; worst of all, he could do nothing to halt the relentless march of the armies of the Arab Caliphate. Heraclius' reign was one of “what might have been?” but at least he saved the empire when at its lowest ebb and founded a dynasty which provided some much-needed political stability in the 7th century CE.

Succession as Emperor

Heraclius was born c. 574 CE, the son of the governor of Carthage, also known as Heraclius. In October 610 CE the future emperor was elected by his father to respond to a plea from the Senate in Constantinople to come and relieve them from the bloody tyrant Phokas (r. 602-610 CE). Heraclius was given command of a fleet which, when it was sighted from Constantinople, caused an immediate rebellion and the overthrow of Phokas right there and then. Heraclius, aged 36, was proclaimed the new emperor, and with his height, good looks, and golden locks he certainly looked the part but his empire was crumbling - already half the size of its former glory - and even more significantly, it was bankrupt.

Military Campaigns

The initial military escapades of Heraclius were nothing short of a disaster, with defeats to the Persians, losing Jerusalem in 614 CE and, in 618 CE, parts of Egypt - the empire's chief grain source. The trend of reverses would continue in North Africa until 629 CE despite the emperor acquiring the Church's valuables in order to pay for his failing armies. Things were so bad that Heraclius seriously considered returning home to Carthage and setting up his capital there but was persuaded to stay on by the bishop of Constantinople Sergios I and the general populace, who knew their fate if Constantinople were abandoned.

Things improved in the east from 622 CE with Heraclius finally going on the attack with his carefully built-up and well-trained army and still powerful navy, gaining several victories against Khosrow II, the Persian king. Back home though, things were not going quite so well, as while the emperor was off campaigning the capital was put under siege by a combined force of 80,000 Avars and Persians in 626 CE. Heraclius sent a third of his army back to defend Constantinople but, crucially, maintained the bulk of his force in Asia.

The capital had to resist the onslaught of siege engines and missiles, the defenders organised by the general Bonos and rallied in spirit by Sergios, who marched the city's population around the walls brandishing an icon of the Virgin Mary. More practical and ultimately successful protection was offered by the city's formidable fortifications. Perseverance paid off for the Byzantines abroad, too, and the Persian army, weakened by the release of contingents to attack Constantinople, was destroyed at the 11-hour battle of Nineveh in 627 CE. Heraclius, leading his army in person in his famously gleaming armour, was said to have killed his opposite number, the general Razates, in single combat, lopping off the Persian's head with one swipe of his sword. As an extra bonus, the Byzantine state coffers were given a much-needed refill after the sacking and looting of Ctesiphon right after the battle, when the conquerors discovered there was, quite literally, too much gold to carry away. Khosrow II was overthrown, a peace was brokered and, when the Persian state all but collapsed in 630 CE, an end was brought to 400 years of wars between the two empires.

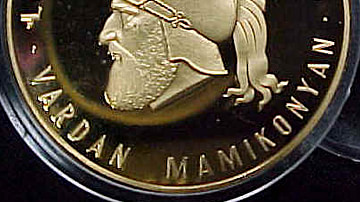

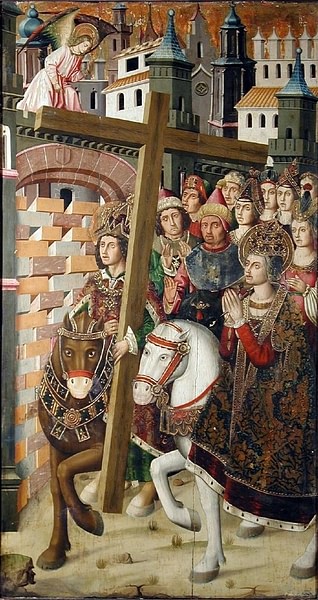

Not only was Heraclius praised for his military victory but also for his recovery of a relic of the True Cross (believed to be the actual wooden cross on which Jesus Christ was crucified). The Persians had stolen the fragment from Jerusalem, but Heraclius recovered and returned it. When the Arabs threatened Jerusalem in 635 CE, the emperor had it brought to Constantinople to rest in the church of Hagia Sophia.

The Byzantine Empire had acquired a new confidence - there was a capable emperor on the throne, and it was felt the time was right to cut some of the old ties with the long-dead Roman Empire. Greek was made the official language, finally sidelining Latin, already a neglected language which lingered only in the laws that so few understood. Even the long-used Roman titles of Augustus and Imperator Caesar were switched to the Greek Basileus ('king').

Despite this optimism, 636 CE would see Heraclius' fortunes plummet again when the Arabs won a decisive victory at the battle of Yarmuk. The Arabs, seemingly risen from nowhere, were led by the brilliant general Khalid who had forged a formidable and highly mobile army using camels. With dissent amongst the Byzantine commanders and a sandstorm at just the wrong time, the Byzantine army was massacred. The defeat at Yarmuk, a tributary of the Jordan River, gave the Arabs control of Syria. They would not stop there, and by the end of Heraclius' reign four years later the Arab caliphate controlled Mesopotamia, Armenia, and Egypt as well. Byzantium had neither the money nor the manpower to prevent the disintegration of the eastern part of the empire.

Ecclesiastical Disputes

During Heraclius' reign, the Church continued to be split by theological arguments without any resolution in sight, notably the debate over Monophysitism versus Dyophysitism - with the former position maintaining that Christ had one inseparable nature which was both divine and human (or just divine) and the latter adherents arguing he had two separate natures. Sergios proposed a compromise, the doctrine of Monoenergism - that Christ had a single energy - and when this failed to persuade the Church in the eastern provinces, he proposed, following an alternative, the idea of Monotheletism - that Christ had one will which united his divine and human natures - which was first proposed by Pope Honorius I (625-638 CE). Heraclius attempted to resolve some of the ecclesiastical debates himself with his decree of 638 CE, the Ekthesis, which supported Monotheletism, but it did not stick as an idea, was opposed by the new pope Severinus, and was condemned by the Ecumenical Council of 680-681 CE. In any case, Heraclius' plan to pacify the two sides of the Church became unnecessary after Byzantium's loss of the eastern parts of the empire.

Succession Dispute

As if Heraclius did not have enough problems defending the empire from without, there were plenty of intrigues to challenge the status quo from within. The chief cause of disturbance seemed to be the emperor's own wife (his second), Martina, also Heraclius' niece. There had been much made of this incestuous marriage by Church and people alike, but the emperor's successes against Persia had nullified the criticism. However, when things started to unravel and the Arab armies sacked one Christian city after another, the people began to whisper that God had abandoned the Byzantines because of the sin of their emperor. The fact that six of the couple's nine children were born deformed or died in infancy added fuel to the theory that God was displeased with Heraclius and it was the people who would ultimately pay the price. The emperor had his own suffering in the form of a disease which aged him beyond his years. Heraclius died in February 641 CE and he was buried in a white onyx sarcophagus in the imperial mausoleum in the Church of the Holy Apostles in his capital.

Martina, meanwhile, conspired so that her own son, Heraklonas, would be nominated as the next emperor. In this, she half-succeeded as Heraklonas shared the throne with his half-brother Constantine III (son of Heraclius and his late first wife Eudokia). Constantine died a mere three months after his father of tuberculosis which, conveniently, gave Martina the opportunity to manipulate her son and effectively rule as regent, although she had the official title of co-emperor. The pair were unpopular and not helped by the loss of Alexandria to the Arabs. Valentinos Arsakuni overthrew them both in September 641 CE, cutting out Martina's tongue, slitting the nose of Heraklonas and exiling both to Rhodes. The mutilations were designed as a permanent mark that they were unfit for office, and it would become a common Byzantine practice from then on. Arsakuni was himself overthrown a few months later by Constans II, the son of Constantine III, who ruled for the next 27 years but fared little better than his grandfather Heraclius in halting the territorial decline of the Byzantine Empire.