The Mamikonians were a powerful clan group who were influential in Armenian political and military affairs from the 1st century BCE onwards. They rose to particular prominence from c. 428 CE to 652 CE in the half of Armenia ruled by the Sasanian Empire when marzpan viceroys represented the Persian king. One of the dynasty's most famous figures is Vardan Mamikonian who fell at the 451 CE Battle of Avarayr fought against Persia to defend Armenia's cultural and religious independence.

Fall of the Arsacid Dynasty

The Arsacid dynasty ruled Armenia from 12 CE and had managed to keep their balance on the diplomatic tightrope strung between the great powers of Rome and Persia for four centuries. By the 5th century CE, though, the Sasanian Empire had begun to expand its influence into areas previously contested between the two Empires. Armenia had already been formally divided between Persia and the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire in 387 CE. The last Arsacid ruler was Artashes IV (r. 422-428 CE) as the Armenian crown, unable to repress the pro-Persian and anti-Christian factions at court, was abolished by Persia in their half of the country (sometimes referred to as Persarmenia). In 428 CE the marzpans were installed, a position which was higher than satraps and more akin to viceroys. Representing the Sasanian king, the marzpans had full civilian and military authority in Armenia and the system would not change until the mid-7th century CE.

The dynasty that now ruled the roost in Armenia was the Mamikonians whose heartlands were in the northern province of Tayk. Their earliest recorded member is Mancaeus who defended Tigranocerta in 69 BCE against Roman attacks. Long a powerful clan group, the Mamikonians had been particularly successful in the military thanks to their ability to raise cavalry forces of 3,000 knights. By the end of the 4th century CE the hereditary office of grand marshal (sparapet), who led the armed forces of Armenia, usually had a Mamikonian lord in the position. Amongst the other noble families the Mamikonians had been only second in importance to the Arsacid royal family itself, indeed two members had even served as regents: Mushegh and Manuel Mamikonian.

Once the ruling house of Arsacid fell, the Mamikonians were left to dominate both Armenian politics and military affairs within the limitations imposed by their Persian overlords. One of the most powerful early Mamikonian princes was Hamazasp, who married Sahakanyush, the daughter of the First Bishop Sakak c. 439 CE. The marriage unified the most prominent feudal and ecclesiastical families in Armenia and the vast territories of the Mamikonians with those of the descendants of Saint Gregory the Illuminator (d. c. 330 CE). Over the next three centuries, seven Mamikonian princes would rule Armenia.

Sasanid Rule

Fortunately for Armenia, Sasanid Persia, although selecting each ruling viceroy, mostly left alone the two key institutions of the Armenian state: the nakharars and the Church. The former were local princes whose ranks and titles were based on the hereditary clans of ancient Armenia, and they governed their own extensive lands as semi-autonomous fiefdoms. Some princes did switch loyalties to the Persians, even converting to Zoroastrianism, in exchange for tax and other privileges under the new regime.

The second institution, the Christian Church founded in Armenia around 314 CE, was not outlawed and crushed. Rather, it was indirectly attacked by the Sassanids through their active promotion of Zoroastrianism, the sending of missionaries from Persia, and reductions in tax privileges for the Church's landed estates. The actual institutions of churches and monasteries themselves, like the nakharars, were largely permitted to keep their lands and revenue, maintain a low profile and live to fight another day.

Matters came to a head with the succession of the Persian king Yazdgird (Yazdagerd) II in c. 439 BCE and his prime minister Mihr-Narseh. Sasanid rulers had long been suspicious that Armenian Christians were all simply spies of Byzantium in Persian territory but both these figures were zealous proponents of Zoroastrianism and the double-edged sword of political and religious policy was about to cut Armenia down to size. The fiscal obligations on the Church were increased, more Persian-friendly bishops were appointed, and a delegation of nobles and clergy invited to Persia was even forced to convert to the Persian religion on pain of death. A military confrontation seemed inevitable, and it came in 451 CE at the Battle of Avarayr (Avarair) when the Armenians faced a massive Persian army.

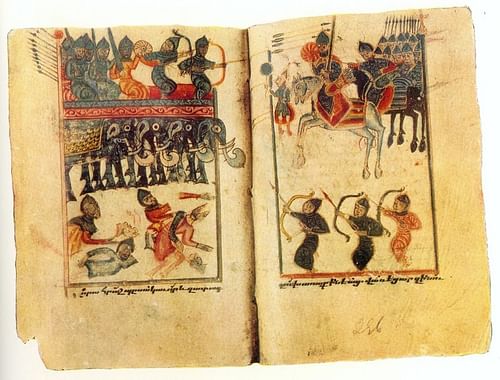

The Battle of Avarayr

The battle was preceded by sporadic outbreaks of open rebellion with Zoroastrian temples burned down and even priests killed. There was also a minor Armenian victory against a small force of Persians in the summer of 450 CE. The crisis peaked, though, in May or June 451 CE on the plain of Avarayr (modern Iran). The 6,000 or so Armenians were led by Vardan Mamikonian, the son of Hamazasp, and they presented a genuinely united front of the anti-Persian aristocracy and Church. Unfortunately for the Armenians, help from the Byzantine Empire was not forthcoming despite an embassy sent for that purpose. Perhaps not unexpectedly, the Persian-backed marzpan, Vasak Siuni, was nowhere to be seen in the battle either.

The Persians, greatly outnumbering their opponents and fielding, besides their ordinary troops, an elite corps of “Immortals” and a host of war elephants, won the battle easily enough and massacred their opponents; 'martyred' would be the term used by the Armenian Church, thereafter. Indeed, the battle became a symbol of resistance with Vardan, who died on the battlefield, even being made a saint. Minor rebellions continued in the next few decades and the Mamikonians, in particular, continued a policy of careful resistance against Persian cultural control. The strategy paid off for in 484 CE the Treaty of Nvarsak was signed between the two states which granted Armenia a greater political autonomy and freedom of religious thought. In this result, the Armenians were helped by the military disasters the Sasanids were enduring on their eastern frontiers and the Persians being fully occupied with the other side of their empire.

Ultimately then, Avarayr was then and still is, seen as a moral victory for Christian Armenia. In political terms, too, the Mamikonians were ultimately successful, as Vahan, the nephew of Vardan, was made the marzpan in 485 CE. During his decade-long reign, Armenia prospered, as is seen in the many new building projects of the period, especially the cathedral at Dvin and many impressive basilicas. Trade also flourished, and the city of Artashat was confirmed as a trading point between the Byzantine and Persian Empires in a Byzantine edict of 562 BCE.

Armenia's zeal for Christianity did bring it closer to the Byzantine Empire and several Mamikonian rulers enjoyed patronage from the emperor in Constantinople when they were given the honorary title Prince of Armenia. However, the Armenian and Byzantine Churches did often differ on matters of dogma. Disagreement with the decrees of the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE opened a rift which would never be closed. Then the Council of Dvin c. 554 CE declared the Armenian Church's adherence to the doctrine of monophysitism (that Christ has one nature and not two) thus breaking away from the duophysitism of the Roman Church. As in politics, Armenian Christians were having to find their own rocky road between east and west.

Movses Khorenatsi

Another important figure from the period of Mamikonian rule was the historian Movses Khorenatsi (Moses of Khoren). Widely known as the father of Armenian history, his History of the Armenians pulled together ancient texts, oral traditions, and the author's own embellishments, and has become the staple historical source of Armenian history ever since it was compiled sometime in the second half of the 5th century CE (although there are some historians who consider Movses to have lived as late as the 8th century CE). The work, at least for western scholars, is notoriously inconsistent with much fabrication but its overall effect is not disputed - it helped to create a sense of continuous history and nationhood for the Armenia people.

Decline & Successors

By the end of the 6th century CE Armenia was again a point of dispute between Persia and the Byzantine Empire and so a re-division was drawn up, which saw Byzantium acquire two-thirds of Armenia. Worse was soon to come, though. In 627 CE a full-scale war against the Sasanids was carried out by the Byzantine emperor Heraclius (r. 610-641 CE) and Armenia was caught in the crossfire. This campaign ended the Sassanid control of Armenia but Byzantine rule was to be short-lived following the dramatic rise of a new power in the region, the Arab Rashidun Caliphate, which conquered the Sasanid capital Ctesiphon in 637 CE.

Armenia was conquered by the Arabs between 640 to 650 CE after decades of playing, as so often before, the role of strategic pawn in a battle of Empires between the Arabs and the Byzantine Empire. Armenia was formally annexed as a province of the Umayyad Caliphate in 701 CE. Although the Mamikonians remained an important clan - several leaders being rallying points for important rebellions in the 8th century CE, their position at the forefront of Armenian politics was ultimately usurped by a new dynasty, the Bagratuni, who would even, by the end of the 9th century CE, establish themselves as the royal family of Armenia.

This article was made possible with generous support from the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research and the Knights of Vartan Fund for Armenian Studies.