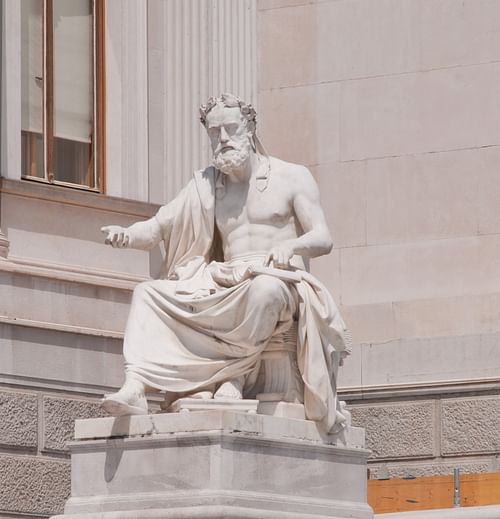

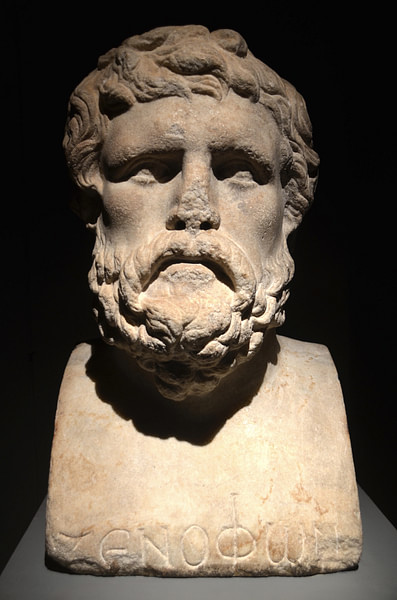

Xenophon of Athens (l. 430 to c. 354 BCE) was a contemporary of Plato and a fellow student of Socrates. He is best known for his Anabasis (The March Up Country) detailing the retreat of the Ten Thousand Greek mercenaries after the defeat of Cyrus the Younger (d. 401 BCE) as well as for his works on Socrates.

Xenophon was highly regarded in his time for his written works including Anabasis, Hellenica, The Cyropaedia, Symposium, Memorabilia, and his Apology, the latter three dealing with Socrates of Athens (l. 470/469-399 BCE). Along with the works of Plato (l. 424/423-348/347 BCE), these three form the basis of what is known of Socrates' life and teachings, as he never wrote anything himself. The historian Diogenes Laertius (l. c. 3rd century CE) claims Xenophon wrote over 40 books, including an important treatise on training dogs. Although Laertius is understood as an often-unreliable source, in this he seems to be correct, as Xenophon is mentioned by others as a prolific writer.

His Anabasis has been widely read and admired for centuries. So precise are Xenophon's descriptions of terrain, distances, cities, and weather conditions that the work was used by Alexander the Great as a field guide for his conquest of Persia in 334 BCE. Anabasis was also later used as a textbook for instruction in Greek in Victorian England and elsewhere because of Xenophon's clear and accessible style.

After his return from the Persian expedition described in the Anabasis, he fought for the Spartan king Agesilaus II (r. 399-358 BCE) as a mercenary against an Athenian coalition and was afterwards exiled from Athens. He lived in Scillus, district of Elis, near Olympia, where he had a farm and wrote his works until 371 BCE when his land was taken by the Elians and he moved to Corinth, where he died c. 354 BCE of natural causes. He is remembered today as one of the greatest writers of ancient Greece, whose Anabasis has inspired many other works including modern-day films.

Early Life & Socrates

Xenophon was born in 430 BCE (though some scholars favor a later date of sometime in the 420s) in Erchia, a suburb of Athens. His father, Gryllus, owned an estate there and was well off but, unlike other wealthy Athenians, played no part in the political life of the city. Nothing is known of Xenophon's mother or whether he had any siblings. He was educated according to the model of any other upper-class Athenian youth and given training in martial arts and horsemanship as befitting a member of the Equestrian class. His later works do not provide much autobiographical information on his youth, but it is known he was an avid hunter and trained his own dogs. According to scholar Robin Waterfield:

Little is known about Xenophon's early life. We do know, however, that [he] was among the well-off young men who associated with the philosopher Socrates, and it is likely that he remained in Athens during the reign of the Thirty Tyrants (404-403 BCE), the junta imposed by the Spartans after Athens' defeat in the Peloponnesian War, and that he fought against the exiled democrats as a cavalryman. (xiii)

Xenophon's own works attest to a close relationship with Socrates, and Diogenes Laertius provides a tale, uncorroborated elsewhere, of their first meeting:

Xenophon, the son of Gryllus, a citizen of Athens, was of the borough of Erchia; and he was a man of great modesty, and as handsome as can be imagined. They say that Socrates met him in a narrow lane and put his stick across it and prevented him from passing by, asking him where all kinds of necessary things were sold. And when he had answered him, he asked him again where men were made good and virtuous. And as he did not know, he said, "Follow me, then, and learn." And from this time forth, Xenophon became a follower of Socrates. And he was the first person who took down conversations as they occurred, and published them among men, calling them Memorabilia. He was also the first man who wrote a history of philosophers. (Book II.6.48)

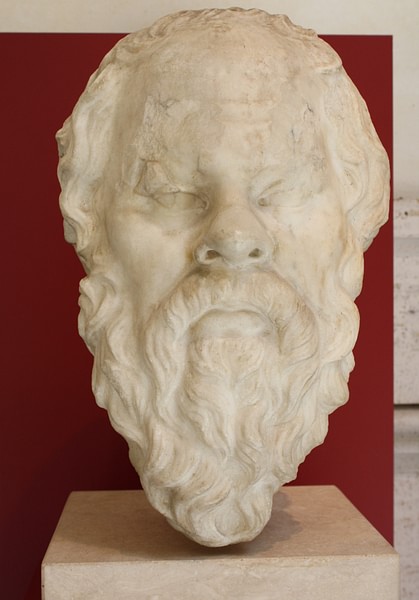

Xenophon's depiction of Socrates contrasts with Plato's in that the latter presents Socrates as an idealistic philosopher who engaged with others to lead them to an apprehension of ultimate truth. Xenophon's Socrates, conversely, is eminently practical and seeks to improve the lives of others by offering advice on moderation, self-control, and the importance of regular exercise and physical fitness. One can still see something of Plato's philosopher in Xenophon's depiction, but the two are hardly identical.

An example of Socrates' practical advice is given by Xenophon in Anabasis 3.I.5-7 when he discusses the invitation to join the expedition in support of Cyrus the Younger. Xenophon asked Socrates' advice on whether he should join the mercenaries, and Socrates sent him to ask the question of the Oracle at Delphi. Instead of asking the direct question of "should I go?", however, Xenophon asked which of the gods were best prayed to for the desired end of a successful journey and safe return. The Oracle answered him with the names of the gods, Xenophon prayed and sacrificed accordingly, and, when he returned to Athens and told Socrates what he had done, the latter scolded him for laziness before telling him that, if the gods had encouraged his participation, he had better go.

This story adds to the portrait of the man as recorded in other ancient accounts of Xenophon. All seem to agree that he was a unique combination of the man of action and the man of letters who chose practicality over abstract philosophy. While it is reported that he tried to emulate Socrates throughout his life, he seems to have done so in his own unique way. Interestingly, this is in keeping with all of Socrates' students, each of whom set up schools and promoted often radically different philosophies from each other while claiming that each was accurately representing Socrates' teachings.

Xenophon never set up such a school himself but is better known than many who did, owing to his Memorabilia depicting Socrates as what scholar Odysseus Makridis refers to as a philosopher who "offers advice that ranges from persuasive marshaling of arguments to practical how-to, nuts-and-bolts instructions" (xiii). Makridis continues:

Those who are familiar with Plato's Socrates might find the Socrates of the [Memorabilia] to be rather unphilosophical. If Plato's Socrates sounds like one of those professors whose class you failed in college, Xenophon's Socrates is the next-door neighbor whose advice you always avidly seek out – from how to make and keep friends, to how to be in good standing with the local sheriff and handle unruly, pestering relatives. This homespun aspect of Socrates is not altogether missing from Plato's writings, but in Xenophon it seems to have absorbed almost everything else. A theory is presented, mantra-like: be smart enough to understand that doing the right thing will keep you out of trouble and might even yield benefits. (xvi)

The Socrates of both Plato and Xenophon reflect the authors' own values, concerns, and upbringing. Xenophon himself seems to have always been more interested in practical matters than idealistic conversation, and so his Socrates is more concerned with offering advice on how to live peacefully with others rather than, as with Plato's Socrates, defining what "peacefully" and "living" truly mean. This same practicality is seen throughout Xenophon's masterpiece, the Anabasis.

Anabasis & Other Works

Although he was later widely admired as a writer, Xenophon initially won fame as a soldier and, especially, as one of the commanders who led the Ten Thousand Greek mercenaries back to Greece through hostile territory, constant hardship, and daily threats.

Anabasis (translated as Up Country, The Expedition of Cyrus, The March Up Country, or March of the Ten Thousand) is Xenophon's narrative of the 401 BCE expedition in support of the Persian prince Cyrus the Younger against Cyrus' brother Artaxerxes II (r. 404-358 BCE) for control of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE). Cyrus' goal was to overthrow his brother and take the throne. Xenophon served as a mercenary in Cyrus' army, but at the Battle of Cunaxa in 401 BCE, Cyrus was killed, and he was left stranded with his troops in enemy territory. The Spartan General Clearchus and the Athenian Proxenus (who had invited Xenophon on the expedition) were betrayed and murdered by the Persians under Tissaphernes who had brokered a truce with them, and Xenophon found himself one of the newly elected leaders of the ten-thousand-man mercenary army.

Xenophon, with fellow commander Chirisophus, helped lead his men through hostile country, fighting their way back home to Greece against the Persians, the Armenians, the Chalybians, Medes, and many others. They endured daily hardships on their way home including enemy attacks, lack of provisions, snowstorms, and the constant threat of betrayal by the local guides they were forced to trust.

Xenophon continued to lead his men until he heard what has become the most famous line from the book, "The Sea! The Sea!" shouted by the men when they reached the Greek territory of Asia Minor and then found welcome at Pergamon. This heroic journey through hostile territory has inspired countless similar works through the years and, in the modern age, the plot for films such as The Warriors (1979) and many science fiction and speculative fiction novels. Waterfield comments on the significance of Anabasis as well as Xenophon's other works:

The [Anabasis] has been admired as much as the march it describes. Xenophon wrote an extraordinarily wide variety of works besides [the Anabasis]: The Cyropaedia, a pseudo-historical account of the upbringing and leadership of the founder of the Persian empire, Cyrus the Great, after whom the prince Xenophon served was named; the Hellenica, a work on contemporary Greek history; the Apology, a version of the defense speech of his one-time mentor Socrates, as well as other philosophical conversations involving Socrates (Memorabilia, Symposium) and the poet Simonides (Hiero); the treatises On Hunting and On Horsemanship, and others on household management, military leadership, and politics; an encomium of the Spartan king Agesilaus; and an economic pamphlet (Ways and Means). At some periods of history, his more didactic and philosophical works have been more popular but, for the last two centuries, the Anabasis has generally been regarded as his masterpiece. (viii)

The appeal of the Anabasis rests on Xenophon's power as a storyteller, his ability to maintain suspense, and his careful use of dialogue, but as Waterfield notes, it is also an engaging – and accurate – historical text:

It can be enjoyed in its own right as a gripping narrative that offers a glimpse of Greek soldiers encountering a foreign world – hunting gazelle in the desert, stumbling on the almost deserted cities of Nimrud and Nineveh, confronting wild mountain tribes who block their way by rolling rocks down steep slopes, sheltering against the harsh Armenian winter in underground homes while restoring their spirits with the local 'barley wine'. Xenophon's narrative also offers a unique insight into the character of a Greek army on the march. We see at first hand the soldiers at leisure, holding athletic competitions amongst themselves. We meet a world marked by the particular forms of Greek religion: vows and sacrifices are frequently made to the gods, seers are constantly consulted, a sneeze is thought to be a favorable omen…Xenophon's account tells us much about the character of Greek soldiers and Greek political life, but it also offers insight into a broader human experience. (viii-iv)

That broader human experience is chiefly characterized in the work by the determination of the Ten Thousand to survive and reach their homes again. Against almost overwhelming odds, and with little hope, Xenophon brought the men back in a heroic journey, which has resonated with audiences since it was first published over 2,000 years ago. Even scholars who have questioned the accuracy of Xenophon's depiction of himself as a heroic leader have admired the work itself.

In addressing critics who claim Xenophon's account is largely self-serving, Waterfield notes that he later refers to the book as having been written by one Themistogenes of Syracuse (Hellenica 3.1.2), which appears to have been a pseudonym and suggests he first published Anabasis under this name "to make his rosy account of his own actions more acceptable" (xix). However that may be, and whatever Xenophon's reasons for writing the work, the return of the Ten Thousand to their homeland is understood as historical fact, and Xenophon's leadership in accomplishing this has never been seriously questioned.

Conclusion

After his return to Greece, Xenophon joined the forces of the Spartan general Thimbron (d. 391 BCE), who was replaced after his failure to capture Larissa by the general Dercylidas c. 399 BCE, a much more experienced leader who took Larissa and eight other cities from the Persians until command was taken by the Spartan king Agesilaus. Initially, Xenophon and his men had been fighting as mercenaries in the Spartan army, but under Dercylidas, they had been commissioned as soldiers so that, by the time Agesilaus arrived, Xenophon, an Athenian, was an officer in the army of Athens' old rival.

At first, this might not have made much difference as Agesilaus was fighting the Persians for the liberation of Ionian Greek Colonies in Asia Minor, but in 395 BCE, the Corinthian War broke out in which an Athenian coalition opposed Sparta in response to its policies regarding two regions in Greece, Locris and Phocis. Agesilaus marched back from Ionia to deal with this situation and met the coalition of Argos, Athens, Corinth, and Thebes at the Battle of Coronea in 394 BCE. The Spartan victory allowed them to take both Phocis and Locris, and so the campaign was regarded by the Spartans as a great success, but for Xenophon, the consequences were less pleasant.

For fighting against his own city-state as a Spartan officer, he was exiled from Athens and lived on a farm in Scillus (in Elis) near Olympia on a property granted to him by the Spartans. He was wealthy enough at this point to have purchased land for a temple to Artemis and paid for its construction. He also seems to have funded the annual festival, including the communal feast and hunting expeditions in which his two sons, Gryllus and Diodorus, participated. Nothing is known of his wife, Philesia, except her name. At his farm in Scillus, he wrote Anabasis, the Socratic works, and others, and it seems to have been the most peaceful and comfortable time of his life.

In 371 BCE, after the Spartans were defeated at the Battle of Leuctra, they no longer had the authority to maintain Xenophon's claim to his estate, and it was taken by the Elians for their own uses, even though it seems clear that Xenophon had hosted the people of the region annually, at his own expense, at the Festival of Artemis and treated them well.

He left Elis for Corinth where, according to Diogenes Laertius, he died c. 354 BCE and was buried. According to other ancient writers, however, his body was returned to Elis, and he was buried in Scillus. His son, Gryllus, a member of the Athenian cavalry, had been killed at the Battle of Mantinea in 362 BCE, and at that time, Athens revoked Xenophon's banishment in honor of his son, but there is no evidence to suggest he ever returned home.