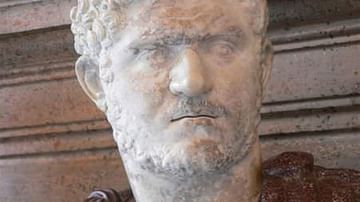

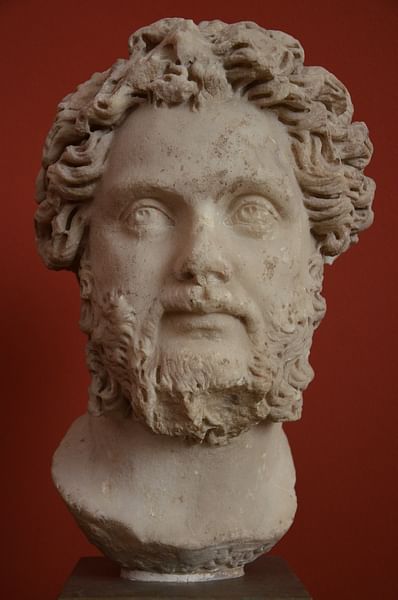

Lucius Septimius Severus was Roman emperor from April 193 to February 211 CE. He was of Libyan descent from Lepcis Magna and came from a locally prominent Punic family who had a history of rising to senatorial as well as consular status

His first visit to Rome was around 163 CE during the reign of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus. He was protected by his cousin Caius Septimius Severus and entered the Roman Senate in 170 CE. When his cousin went to Africa as a proconsul around 173-174 CE, he chose L. Septimius Severus to be his legatus. L. Septimius married Paccia Marciana around 175 CE who had Punic origins like him; however, she died ten years later. When he was governor of Gaul and he lived in Lugdunum (Lyon), he married Julia Domna from Emesa (Syria) around 187 CE. She was descended from a family of great priests of Eliogabal.

Septimius' rise to emperor began with the murder of the dissolute ruler Commodus on the last day of 192 CE. Commodus' immediate successor, the well-respected if elderly Pertinax, was quickly made emperor afterwards. Pertinax's actions as emperor, however, enraged members of the Praetorian Guard who disliked his efforts to enforce stricter discipline. Moreover, the inability of Pertinax to meet the Guard's demands for back pay led to their revolt which ended in the emperor's assassination. The Praetorian Guard then cynically proceeded to auction off the imperial throne to the highest bidder with the person willing to pay the most being promised the support of the Praetorian Guard and therefore the imperial throne. A rich and prominent senator, M. Didius Julianus, perhaps as a joke at first, proceeded to outbid all others at the auction and thus was proclaimed emperor by the Praetorians solely for the reason that he promised to pay them the most money. This affair caused considerable resentment among the population at Rome who openly denounced Julianus and the way in which he acquired the throne. Word of such unrest at Rome spread to the provinces and led to the emergence of three possible candidates to challenge Julianus' rule.

The first candidate was Clodius Albinus, governor of Britain. The second was Pescennius Niger, governor of Syria, and the third was, of course, Septimius Severus who governed the province of Pannonia Superior on the Danube frontier. All three governors emerged as possible candidates mainly because each of them held provinces that were defended by three legions apiece. Not only did this give each governor a powerful military base of three legions but also ensured that the provinces adjacent to them would more often than not join in their cause if they decided to rise up and make a bid for imperial power. Both Albinus and Niger did so. Septimius, in making his claim, had an edge over these two men. He had an advantage not only in terms of propaganda (Septimius had served with Pertinax previously and successfully portrayed himself as the 'avenger of Pertinax,' even adopting the slain emperor's name) but also in terms of location as Pannonia was the closest of these provinces to Italy and Rome. To prevent a possible clash with Clodius Albinus in Britain, he secured Albinus' support mainly by promising him the title of Caesar and thus a place in the imperial succession should Septimius be successful. After securing the loyalty of the sixteen legions of the Rhine and Danube to his cause, Septimius marched into Italy and, 60 miles outside of Rome, was recognized by the Senate as emperor. Julianus was executed, and Septimius was welcomed into Rome on 9 June 193 CE. With his accession, the year 193 CE is known as 'The Year of Five Emperors.'

Septimius quickly dissolved the existing Praetorian Guard and replaced it with a much larger bodyguard recruited from the Danubian legions under his command. To strengthen his rule in Italy, he also raised three new legions (I-III Parthica), based the second of these not far from Rome at Alba, and increased the city of Rome's number of vigils, urban cohorts, and other units, greatly enlarging Rome's overall garrison.

Having now secured Rome (and, for the moment, Albinus' loyalty in the west), Septimius now organized a campaign to march to the eastern provinces to eliminate his rival Niger. Severan forces handed out successive defeats to Niger, driving his forces out of Thrace, then defeating him at Cyzicus and Nicaea in Asia Minor in 193 CE, and ultimately defeating him at Issus in 194 CE. While in the East, Severus turned his forces against the Parthian vassals who had backed Niger in his claims. He quickly subdued the kingdoms of Osroene and Adiabene, taking the titles Parthicus Arabicus and Parthicus Adiabenicus to commemorate these victories. To solidify his reputation and attempt to link his new dynasty with that of the Antonines, he declared himself the son of the now deified former emperor Marcus Aurelius and brother of the deified Commodus. Moreover, he conferred upon his eldest son M. Aurelius Antoninus (later the emperor Caracalla) the title of Caesar. This last move led him into direct conflict with his erstwhile ally Clodius Albinus who was initially given this title in return for his loyalty. Realizing that Severus intended to discard him, Albinus rebelled and crossed with his legions into Gaul. Severus hurried west to meet Albinus in battle at Lugdunum and defeated him in a bloody and hard fought battle in February 197 CE. After defeating Albinus, Severus was now the sole emperor of the Roman Empire.

![Arch of Septimius Severus, Rome [Side View]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/1340.jpg?v=1619458202)

In the summer of 197 CE, Severus once again travelled to the eastern provinces where the Parthian Empire had taken advantage of his absence to besiege Nisibis in Roman occupied Mesopotamia. After breaking the Parthian siege there, he proceeded to march down the Euphrates attacking and sacking the Parthian cities of Seleucia, Babylon, and ultimately the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon. He would have liked to have continued his campaigns deeper into the Parthian Empire, although Dio states that he was prevented from doing so due to a lack of military intelligence and knowledge that the Romans had of the Parthian heartland. Septimius then turned against the fortress of Hatra in Iraq, but failed to take it after two attempted sieges. After coming to a face-saving agreement with Hatra, Septimius declared victory in the East, taking the title of Parthicus Maximus (indeed, the Senate voted him a Triumphal Arch in the Roman Forum which still stands today). It was during this time that he organized the lands of northern Mesopotamia, captured from the Parthians, into the new province of Roman Mesopotamia which Dio states Severus hoped would serve as a 'bulwark for Syria' against any future Parthian invasions (how effective this policy was in the years after Severus' reign is a matter which is open to debate).

Severus then travelled to Egypt in 199 CE, reorganizing the province. After returning to Syria for a year's stay (end of 200 to beginning of 202 CE), Severus finally travelled back to Rome in summer 202 CE to celebrate his decennalia with a victory game as well as giving his son Antoninus in marriage to the daughter of his confidant, the Praetorian Prefect Plautianus (who was later murdered thanks to the intrigues of Antoninus). In autumn of that same year, Severus travelled to his homeland of Africa, touring (and greatly patronising) Severus' home town of Lepcis Magna, as well as Utica and Carthage. At Lepcis Magna, he conducted an energetic program of monument building, providing colonnaded streets, a new forum, a basilica, and a new harbor for his hometown. He also used this time to crush the desert tribes (most notably the Garamantes) who had been harassing Rome's African frontiers. Severus expanded and re-fortified the African frontier, even expanding Rome's presence into the Sahara thus curtailing the raiding activities of these border tribes who could no longer attack Roman lands with impunity and then escape back into the desert.

Severus then returned to Italy in 203 CE where he stayed until 208 CE, holding the Secular games in 204 CE. With the murder of his Praetorian Prefect Plautianus, Severus replaced him with the jurist Papinian. His patronage of this new prefect as well as the jurists Ulpian and Paul made the Severan era a golden one for Roman jurisprudence.

In 208 CE, small scale fighting on the frontier of Roman Britain gave Severus the excuse to launch a campaign there which would last until his death in 211 CE. With this campaign, Severus was hoping for a chance to achieve military glory. Moreover, he brought with him his sons Antoninus and Geta in the hopes of providing them with some administrative and military experience necessary for holding the imperial power (until this point, the two sons had spent their time violently quarrelling with each other as well as behaving like libertines carousing at Rome's less reputable establishments).

Severus' intentions in Britain were almost certainly to subdue the entire island and bring it under Roman rule completely. In order to do this, Severus completely repaired and renovated many of the forts along Hadrian's Wall with the intention of using the Wall as a base from which to launch a campaign to conquer the north of the island of Britain. Leaving Geta south (supposedly leaving him responsible for the civil administration of Britain south of the wall), Severus and his son Antoninus campaigned in the north, especially in what is now Scotland. The course of the campaign was one that was mixed for the Romans: the native Caledonian tribes did not meet the Romans in open battle and engaged in guerrilla tactics against them and caused the Romans to suffer heavy casualties. By 210 CE, however, the northern tribes sued for peace, and Severus used this opportunity to build a new advance base at Carpow on the Tay for future campaigning. He also took the title Britannicus for himself and his sons to commemorate this victory. This success was short-lived, however, as the tribes soon rose up in revolt. By this time (211 CE), Severus could not continue his campaigns against them. He was a long-time sufferer of gout which appears to have taken a toll on him: He died at Eburacum (York) on 4 February 211 CE.

Severus' reign witnessed the implementation of reforms in both the provinces and the military which had long term consequences. After the defeat of his rivals, Severus resolved to not have another take power in the fashion that he did. Consequently, he divided the three legion provinces of Pannonia and Syria to discourage future governors to rise up in revolt (Pannonia was divided into the new provinces of Pannonia Superior and Pannonia Inferior; Syria was divided into Syria Coele and Syria Phoenice). Britain was also divided into two provinces (Britannia Superior and Britannia Inferior), although it is debated whether or not Severus or his son and successor Caracalla did this.

Severus is also noted for his reforms of the army. Not only did he greatly increase the size of the army, in order to ensure its loyalty he also raised the annual pay of the soldiers from 300 to 500 denarii (many would have seen this pay rise as overdue, as the last raise in soldiers' salaries was granted by the emperor Domitian in 84 CE). Severus, to pay for these raises, had to debase the silver coinage. It seems that the long term effects this may have had on inflation were minimal, although Severus set a precedent for future emperors to continuously debase the coinage in order to pay for the army. The historians Dio and Herodian criticized Severus for these pay rises, mainly because it put more financial pressure on the civilian population to maintain a larger army. Moreover, Severus ended the ban on marriage which had existed in the Roman army, giving soldiers the right to take wives. This measure has been argued by some to be a positive reform as it gave legal rights to the wives of soldiers who before the ban had no legal recourse as their relationships were informal and not legally binding. So concerned was Severus with the loyalty of the army that, on his deathbed, he is said to have advised his two sons to 'Be good to one another, enrich the soldiers, and damn the rest.'

Severus could be ruthless towards his enemies. When he defeated Niger in the East, not only did he attack many of the cities in that region which supported his rival, he is noted for taking metropolitan status away from the city of Antioch (Niger's base of operations), and giving it to its chief rival, the city of Laodicaea. After defeating Albinus at the battle of Lugdunum, Severus released his wrath on the Roman Senate, many of its members having given either muted or open support to Albinus. Severus, after declaring his intentions to purge the Senate in a speech to that body in 197 CE, proceeded to execute 29 senators of that body for having supported his rival (many other non-senatorial supporters of Albinus met the same fate).

Despite emerging victorious from a period of civil war and bringing stability to the empire, Severus' sense of accomplishment may have been mixed. His last words, according to various historians, seem to imply that he felt he may have left his work unfinished. Aurelius Victor reported that Severus, on his deathbed, despairingly declared 'I have been all things, and it has profited nothing.' Dio, who knew Severus personally, wrote that, as the emperor expired, he gasped 'Come, give it to me, if we have anything to do!'