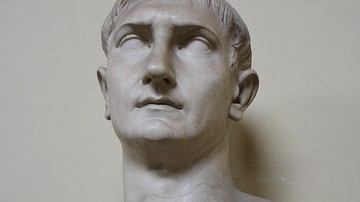

Domitian was Roman Emperor from 81 to 96 CE and his reign, although one of relative peace and stability, became engulfed in both fear and paranoia. His death at the hands of those who were closest to him brought an end to the short dynasty of the Flavians and it was those emperors who would follow, at least for the next one hundred years, who would see a rebirth of some of the grandeur and power of old Rome.

Early Life

Titus Flavius Domitianus, Domitian, was born October 24, 51 CE on Pomegranate Street in the sixth district of Rome, youngest son of the future emperor Vespasian (64 -79 CE); his mother, Flavia Domitilla Major, died in his youth. Unlike his much older brother, Titus, he did not share in the court education, although many considered him bright. According to historian Suetonius, his “rather degraded youth” was spent in poverty. In December of 69 CE, while Vespasian was battling in the eastern provinces in an attempt to secure the throne away from Emperor Vitellius, Domitian was in Rome with his uncle Flavius Sabinus. When Vitellius's forces besieged Rome and set fire to the temple where Domitian was hiding, he was able to escape with a friend across the Tiber to safety.

When Flavian forces entered the city, Domitian returned to Rome becoming, albeit temporarily, the representative of the Flavian family; he was even hailed by Roman citizens as “caesar”; however, most of the administrative decisions were left to others. Vespasian returned to the city in October of 70 CE and was immediately hailed as the new emperor. Afterwards, although given titles and honours, Domitian never sought any real responsibility and was given little by either his father or later his brother, a poor preparation for a future emperor.

A Popular Emperor

His ascension to the throne came on September 14, 81 CE when Titus died of natural causes while he and his brother were travelling outside Rome. Later, rumours circulated that Domitian may have had a hand in his brother's death, possibly by poison. Gossip also ran rampant that the new emperor had at one point even plotted to overthrow his brother and take the throne for himself. Whether or not he had a hand in Titus's death, Domitian did not wait for his brother to die. He quickly returned to Rome and the Praetorian camp to be proclaimed emperor. Mystery, however, surrounded the last minutes before Titus's death. There is some disagreement on the meaning of Titus's last words: “I have made but one mistake.” Suetonius wrote he “gazed up at the sky, and complained bitterly that life was being undeservedly taken from him, since a single sin lay on his conscience.” He added, “… this enigmatic remark has been taken as referring to incest with Domitian's wife, Domitia, she herself solemnly denied the allegation.” Suetonius did not believe this was the case because if she had had an affair, she would have bragged about it. Some, those not overly fond of the new emperor, took a more negative view of these words - Titus meant he should have killed Domitian when he had the chance.

Early in his reign, Domitian proved to be an able administrator and did not ignore the welfare of the people. Before the Flavians came to power, much of Rome needed rebuilding, mostly due to fire, decay, and the failure of previous emperors to do anything about it. He restored the gutted ruins of many public buildings, including the Capitol which had burned in 80 CE, built a new temple to Jupiter the Guardian, a new stadium, and a concert hall for musicians and poets. For himself, because he didn't like the old imperial palace, he built a new Flavian Palace on Palatine Hill for official functions, and to the south he constructed the Domus Augustana where he held numerous banquets and receptions. Despite his own lack of moral values, he attempted to raise the standards of public morality by forbidding male castration, admonishing senators who practiced homosexuality, and censuring the Vestal Virgins for, among other indiscretions, incest - one was even buried alive (her lover was also executed). By those around him, at least early in his reign, he was viewed as being generous, possessing self-restraint, considerate of all of his friends, and conscientious when dispensing justice.

Domitian also liked games, in particular, chariot races, even adding two new factions - Golden and Purple. In fact, he loved public entertainments of any kind, especially those involving women and dwarves. There were also wild beast hunts and gladiatorial contests by torchlight and there were competitions to the death between infantry and cavalry. The basement of the Colosseum (built by his father) was flooded and used for a naval battle. He even founded a festival of music, horsemanship, and gymnastics that was to be held every five years. However, while both Domitian and the public enjoyed these entertainments, their cost would eventually take a heavy toll on his and the empire's finances.

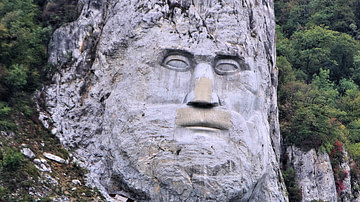

Although not a military man (unlike Vespasian and Titus), he considered himself one and constantly sent messages to the generals in the field with advice and recommendations. Having no personal experience himself and hoping to claim some credibility with the army, he embarked on a victorious campaign to Germany to engage the Chatti in 83 CE. Afterwards, he awarded himself the title of Germanicus for his “success.” In 85 CE the Dacians crossed the Danube onto the northern frontier, killing a Roman commander. Four years later, the Roman army won another decisive victory at Tapae; however, Domitian was forced reluctantly to conclude a truce with King Decebalus. In 92 CE, the Sarmatians crossed the Danube and attacked the Roman frontier, a war that would endure until after the emperor's death. Despite the results of his military achievements, he earned the respect of the army when he became the first emperor since Augustus to give them a raise.

The Paranoid Emperor

In his The Twelve Caesars Suetonius claimed that Domitian was not evil to begin with; however, greed and fear of assassination made him cruel. Historian Cassius Dio in his Roman History said the emperor was both bold and quick to anger. He was treacherous as well as secretive, feeling no affection for anyone (except women). He was extremely vain and very self-conscience of his being bald. As his reign progressed and the pressures of ruling mounted, his paranoia seized him. In order to pay for his extravagances, he tightened the Jewish tax enacted by his father and seized the fortunes of senators and wealthy Romans. His paranoia even extended to his wife, Domitia Logina. He accused her of adultery (some accounts claimed she deserved it) and planned to put her to death, a common practice for the time. Domitia had been married to a senator, Aelius Lamia, but he was convinced to divorce her so she could marry Domitian. Domitian temporarily left his wife to live with his niece Julia, Titus's daughter by his second marriage, until he was convinced by others to return to his wife.

The emperor saw himself as an absolute ruler and took pride in being called master or god: “dominus et deus.” He even renamed two of the months after himself - Germanicus (September) and Domitianus (October). The Senate was almost stripped entirely of its power and his paranoia led to the execution of both senators and imperial officers for the most trivial of offences. Out of jealousy, he had Sullustius Lucullus, governor of Britannia, executed for naming a new type of lance after himself and he recalled Agricola, a victorious general in Britain because he became too popular.

In his book On Britain and Germany Tacitus recounted the tenuous relationship between Agricola and Domitian. The general's victories in Britain put the emperor in a precarious position as he was torn between pride for a Roman victory (and keeping up appearances to the public) and jealousy because of his own failure as a commander. “Agricola…was received by Domitian with the smile on his face that so often masked a secret disquiet. He was bitterly aware of the ridicule that had greeted his sham triumph over Germany….”. Upon returning to Rome, the general was offered the governorship of Syria but refused. His death at the young age of fifty-four, again, put Domitian in a difficult position. “Domitian made a decent show of genuine sorrow; he was relieved of the need to hate, and he could always hide satisfaction more convincingly than fear.”

His paranoia led him to take extreme measures such as employing informers. As a means to obtain information on possible plots or rebels, he ordered interrogators to cut off the hands (or scorched the genitals) of prisoners. He lined the gallery where he took his daily walks with highly-polished moonstone so that it reflected everything behind him. He executed another niece's husband Flavius Clemons on the charge of atheism because he was sympathetic to the plight of the Roman Jews. However, plots against the emperor did exist. In September of 87 CE, several senators were implemented in a conspiracy and were executed and a mutiny by Lucius Antonius Saturninus, governor of Upper Germany, in 89 CE was stamped out.

Death

The final conspiracy against his life, however, was successful - a plot that even suggested the approval of Domitia herself (she remained fearful of her life.) According to Suetonius and others, a group of conspirators (they had heard their names were on a “list”) were debating on whether to assassinate the emperor in his bath or at dinner. Stephanus, a member of Domitian's imperial staff (he had been accused of embezzlement and feared for his life) approached the conspirators, offering his services. For several days he faked an arm injury and wore a protective wrapping; however, the bandage concealed a dagger. Approaching Parthenius, Domitian's valet, he said he had a list of possible conspirators and as Stephanus approached the emperor, he pulled out the dagger and stabbed the unsuspecting Domitian in the groin. The two men struggled with Domitian reaching for the knife he kept under his pillow but Parthenus had removed the blade. Then other conspirators hurried into the room and hacked the emperor to death. He was only forty-four years old. His ashes were taken by his old nurse Phyllus and interred in the Temple of Flavian.

On hearing of his death, the Roman Senate was overjoyed. Suetonius wrote, “The Senators, on the other hand, were delighted and thronged to denounce Domitian in the House with bitter and insulting cries. Then, seeking for ladders, they had his images and the votive shields engraved with his likeness, brought smashing down….” Immediately, Marcus Cocceius Nerva was hailed as the new emperor - a temporary fix until someone better could be found. In the months that followed, the city celebrated the death of the old emperor by turning over his statues and ceremonial arches, however, the Praetorian Guard would not take the assassination lightly and eventually many of the conspirators would meet their own deaths.