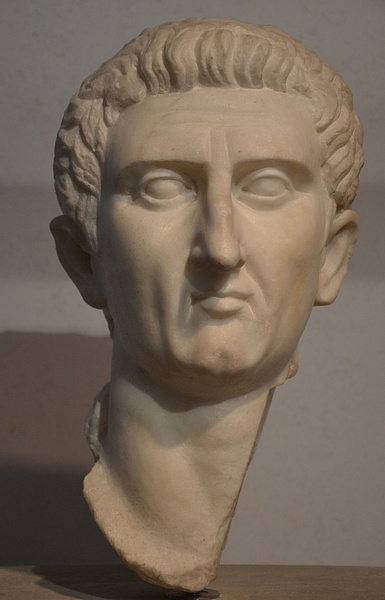

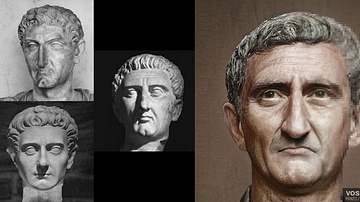

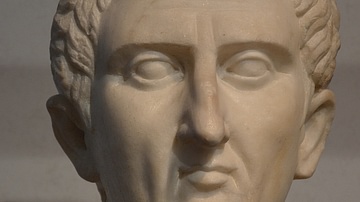

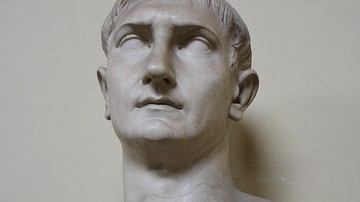

Marcus Cocceius Nerva was Roman emperor from 96 to 98 CE, and his reign brought stability after the turbulent successions of his predecessors. In addition, Nerva helped establish the foundations for a new golden era for Rome which his chosen successor Trajan would bring to full fruition.

The End of the Flavian Dynasty

The assassination of the Roman emperor Domitian (r. 81-96 CE) brought an end to the short-lived Flavian Dynasty, a dynasty started by his father Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE), in the year of the four emperors, 69 CE. Since Domitian left no surviving heirs, the throne of the empire was left vacant. In order to avoid possible civil unrest, violence, or a civil war, a temporary or quick fix appointment was necessary, at least until a better candidate could be found. The answer to the problem came in the form of a man already ill and old even by Roman standards, Nerva.

Nerva was an ideal candidate, one who presented a sharp contrast to his predecessor. Domitian had not been groomed to become an emperor, as his older brother Titus (r. 79-81 CE) had been. However, the sudden death of Titus brought Domitian to the throne. Although he proved himself a capable administrator, he saw the role of the emperor as one vested with absolute power and the Senate was all but stripped of its authority. While he did not neglect the welfare of the empire, he executed or exiled those who opposed him. Near the end of his reign, after an assassination plot failed, paranoia seized the emperor, causing him to rely heavily on informers. This paranoid behaviour led to cruelty and executions, a real “reign of terror.” And it also led to his death.

The sudden appointment of someone with no ties to the throne caused many to question why the relatively obscure Nerva had been chosen. According to the historian Suetonius, Nerva had “debauched” Domitian in his youth, but this was only imperial palace gossip. There was speculation that he had been approached by the conspirators in Domitian's death, although there was little evidence to support these claims. Possibly he had accepted the throne to save his own life because he was in danger of facing treason charges by the former emperor and faced exile.

Nerva Rises to Power

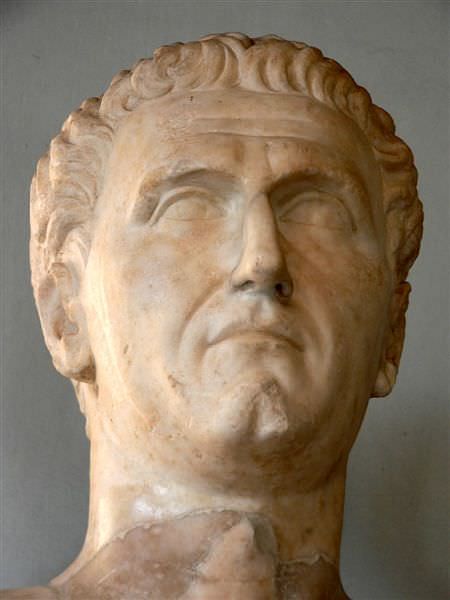

The new emperor was born on November 8, 35 CE in the small town of Narnia in Umbria, 50 miles north of Rome. He came from a distinguished Roman family - his father was a wealthy lawyer, his grandfather had been a member of the imperial entourage at the time of Nerva's birth, his great-grandfather had been a consul in 36 BCE, and his aunt was the great-granddaughter of Emperor Tiberius. He had held a number of official positions under various emperors during both the Julio-Claudian and Flavian dynasties, helping Emperor Nero suppress the Piso Conspiracy in 65 CE (receiving special honours, the ornamenta triumphalia) and serving as co-consul under both Vespasian and Domitian. Because of the lyric pieces he penned, Nero even recognized him as the Tibullus of his age. Unrelated to anybody before him by either marriage or blood, his ascension would usher in an era English historian Edward Gibbons called “The Five Good Emperors”- Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius. It would be a time of relative peace and stability; unfortunately, it was followed by one of weak emperors and insecurity.

Although the army would be the only ones to mourn Domitian's death, the Roman Senate, who had tired of Domitian's tyranny, welcomed Nerva, quickly recognizing him as emperor on September 18, 96 CE; they even granted him the title of pater patriae or “father of the country.” The general populace also seemed to welcome him, sensing a release from the harsh rule of Domitian; however, the first few months of his reign were troubled ones - statues of Domitian were destroyed and ceremonial arches were toppled. Nerva executed many of Domitian's informers and granted amnesty (returned seized property as well) to those who had been exiled. According to Cassius Dio, he “put to death all the slaves and freedmen who has conspired against their masters.” And, as it was the practice of all newly named emperors, he promised not to execute any senators. Eventually, “a sense of euphoria” returned to the empire; justice had been restored.

Opposition

While the citizenry and the Senate welcomed the new emperor, there remained many who overlooked Domitian's cruelty and sought revenge for his death, particularly, the army (more specifically the Praetorian Guard). He had given them the only pay raise they had received since Emperor Augustus. In 97 CE a mutiny of the Praetorian Guard occurred under the leadership of their commander, Casperius Aelianus. They imprisoned Nerva in the imperial palace, demanding the release into their custody of Petronius and Parthenius, two of the men responsible for Domitian's death. Nerva resisted, offering his own neck to slit, but this gesture was ignored, and the conspirators were seized and executed - Petronius was killed by a single-sword blow while Parthenius had his throat slit after his genitals were cut off and stuffed into his mouth. Although unharmed, the incident not only damaged Nerva's authority - one cannot rule without the support of the military - but left him visibly shaken (he even thought about abdicating), making him question not only his own possible death but also who would succeed him.

Without an heir of his own (there's no evidence that he ever married), he realized his only option was adoption, and he chose as his “son” Marcus Ulpius Traianus, Trajan (r. 98-117 CE), the governor of Upper Germany. The adoption took place in a public ceremony in October of 97 CE (Trajan was not present). It should be noted that Nerva had been the one who had appointed him as governor of Upper Germany, and since Nerva knew little about foreign affairs and lacked any military experience, the appointment of Trajan was made not only to provide an heir but to secure the northern provinces.

Legacy

Nerva's limited political experience demonstrated to those around him that he lacked decisiveness and originality. Yet, despite his relatively short reign of only sixteen months and his tendency to consult the Senate on all policy-making decisions, he did much to stabilize the empire. He dedicated a new forum that had been begun by Domitian - named in his honour, Forum Nervae. Although some claim his reforms were only to gain popularity, he repaired roads and aqueducts, built granaries, repaired the Colosseum after the Tiber flooded, allotted land to the poor, relaxed a Jewish tax enacted by Vespasian, ordered a reduction in the number of public games, and tightened the purse strings - the latter was an attempt to balance the budget.

Nerva was far from a typical emperor, forsaking the imperial palace, choosing to live in Vespasian's old residence. His adoption of Trajan enabled him to live the remainder of his life in peace. He reportedly said, “I have done nothing that would prevent me laying down the imperial office and returning to private life in safety.” On January 28, 98 CE Nerva died, and on Trajan's orders was laid to rest in the Mausoleum of Augustus; an eclipse of the sun appeared on the day of his burial. His ascension to the throne and adoption of Trajan initiated a series of adopted successors and Trajan would bring about a golden age throughout the empire.