Leptis Magna (aka Lepcis Magna), located in western Libya, North Africa, was a Phoenician city founded by Tyre in the 7th century BCE. Continuing to be a major city in the Roman period, it was the birthplace of Emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193-211 CE). Leptis Magna, thanks to its impressive ruins such as the Augustan Theatre, forum and Tetrapylon arch, is listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

Phoenician Settlement

The coastal town of what the Romans would later call Leptis Magna was established in the second half of the 7th century BCE by a natural harbour at the mouth of the Wadi Lebda river by Phoenician colonists from Tyre. The pre-Roman history of Leptis, then perhaps called Lpqy, is patchy due to sparse archaeological evidence, but there was originally a four-sided open area which likely acted as a public forum, a 4th-century BCE necropolis (covered by the later Roman theatre), and temples dedicated to the town's two patron gods Shadrapa and Milk'ashtart. The town prospered largely thanks to the production and export of olive oil but was not without its rivals, notably the Greek colony of Cinyps a mere 18 km (11 miles) east along the coast.

The Roman Period

In the 2nd century BCE, the city gained favour by supporting Rome during the Third Punic War with Carthage (149-146 BCE). In the 1st century BCE, the city then chose the wrong side to back during Rome's civil war between Julius Caesar (l. 100-44 BCE) and Pompey the Great (l. 106-48 BCE). Caesar was victorious in 48 BCE, and he swiftly imposed an annual fee on the town of a massive three million pounds of olive oil for its error of judgement. The Romans did construct a dam and canals around the city to better manage the regular floodwaters of the Wadi Lebda river.

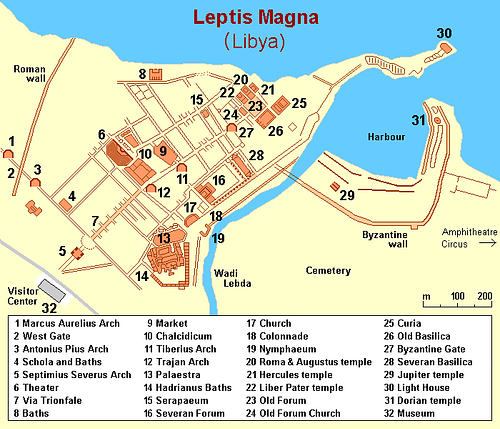

Most of the ruins at the site today date to the Roman period, and the majority date to the reign of Augustus (r. 27 BCE - 14 CE) or later. Nevertheless, they often display an interesting mix of Punic and Roman architectural styles. The large Augustan theatre has a collonaded stage and the market or macellum dates to the same period. We know that both of these structures were bankrolled by a local aristocrat, the splendidly named Annobal Tapapius Rufus. The market was unusual with its two semi-circular market halls, and the stones which had the standard Roman measures of length and volume carved into them can still be seen today. Other notable Roman structures include the Chalcidium, a collonaded building of uncertain function (probably commercial) and a temple dedicated to the Augustan family and Rome. The latter boasted two fine statues of Augustus and his wife Livia, and these are now on display in the Archaeological Museum of Tripoli. Leptis Magna was made a Roman municipium in 64 CE.

Around 110 CE, the city was granted the formal status of Roman colonia, which gave it voting rights back in Italy. In connection with this event, the Forum of Trajan and the Arch of Trajan were built. A new aqueduct was constructed during the reign of Hadrian (117-138 CE), again paid for by a local aristocrat, this time one Quintus Servilius Candidus. Another addition to the city's amenities was a Roman baths, built using marble and brick, which was set beside a huge palaestra space. Already boasting an amphitheatre (56 CE), circus (whose starting gates have survived remarkably well) and many large villas (whose floor mosaics are another lasting testimony to the city's prosperity), Leptis Magna was fast becoming one of the jewels of the Roman Empire, and the neighbouring coastline became a favourite spot for aristocrats to build their villas.

The Septimius Severus Effect

In the late 2nd century CE the good times continued, indeed they got even better, and the city produced its most famous son, future Roman emperor Septimius Severus. Born into a local aristocratic family, Septimius would ensure his hometown did not lack for investment. Rather unashamedly, as the historian M. Wheeler puts it, "he lavished upon his birthplace a wealth of artistry in excess of its economic and political significance" (53).

Consequently, Leptis Magna became second only to Carthage as the most important city in Roman North Africa. A whole new wave of urban renewal began to honour the city's association with the most powerful man in the ancient world. While local yellow limestone was the main source of building material, the imperial purse splashed out on much more expensive and rarer stone for decorative highlights and columns such as gleaming white Pentelic marble and green Carystian marble from Greece, grey-veined white Proconnesian marble from Turkey, and red Egyptian granite.

A new forum was built measuring 305 x 183 metres (1000 x 600 ft), and one of the finest basilicas in the Empire was constructed which had three aisles, two apses, and highly decorative sculpture of scenes showing the Severan family deities of Dionysos and Hercules. Reaching a height of around 30 metres (100 ft), the basilica was so ambitious, it took until the reign of Caracalla (211-217 CE) to complete.

Other works carried out as part of Septimius Severus' aggrandisement project included the extension of the harbour and its docking facilities - a lighthouse, quays, a watchtower, warehouses and a temple. Perhaps indicative of the 'don't worry if we don't really need it' approach to city-planning, the completed harbour seems to have been little used and was already silted up by the end of the 3rd century CE. A collonaded street was built to connect the baths with the rest of the city and harbour, and a large public fountain (nymphaeum) was erected. The emperor even got his own commemorative arch, the distinctive four-sided Tetrapylon, likely set up to honour Septimius' trip back home in 203 CE. The arch stood at the principal crossroads of the city but was placed on its own island and so was not meant to be used as a passageway. Like many other Roman structures of the period, its decoration reflects the art and architecture of the Near East. Now at its peak, the city covered some 425 hectares (660 acres) making it one of the biggest in the Roman Empire.

One final architectural feature of note, located just outside the city itself, is the so-called 'Hunting Baths', perhaps built at the end of the 2nd century CE. This building, likely used by animal hunters who supplied their captures to circuses and amphitheatres, if the subject of one of its wall mosaics is anything to go by, has a perfectly-preserved multiple-domed roof made of concrete. The building and its mosaics and murals are in a remarkable state of preservation thanks to the fact that it was completely buried under sand dunes for 17 centuries.

Decline

Leptis, along with Sabratha and Oea, was part of the Roman province of Tripolitania (modern western Libya), and the city was made the province's capital by Emperor Diocletian (r. 284-305 CE). As the 4th century CE wore on, though, the city suffered increasingly from raids by North African tribesmen. The city had built fortifications as early as 69 CE to ward off raids by the Garamantes Berbers, but in 365 CE Leptis Magna was devastated by the Berber Austuriani. The region's fortunes improved somewhat in the 6th century CE when the Byzantine Empire took a greater interest in North Africa, but the city's economic importance was now much reduced and, as a consequence, so too was the size of Leptis Magna. The reduced urban area, now a mere 38 hectares or 95 acres, was protected by a defensive wall, the remains of which can still be seen today. Also in the 6th century CE, the basilica was converted into a Christian church. The ancient site was rediscovered and systematically excavated by Italian archaeologists from 1920 CE.