Roman baths were designed for bathing and relaxing and were a common feature of cities throughout the Roman empire. Baths included a wide diversity of rooms with different temperatures, as well as swimming pools and places to read, relax, and socialise. Roman baths, with their large covered spaces, were important drivers in architectural innovation, notably in the use of domes.

A Mainstay of Roman Culture

Public baths were a feature of ancient Greek towns but were usually limited to a series of hip-baths. The Romans expanded the idea to incorporate a wide array of facilities and baths became common in even the smaller towns of the Roman world, where they were often located near the forum. In addition to public baths, wealthy citizens often had their own private baths constructed as a part of their villa and baths were even constructed for the legions of the Roman army when on campaign. However, it was in the large cities that these bath complexes (balnea or thermae) took on monumental proportions with vast colonnades and wide-spanning arches and domes. Baths were built using millions of fireproof terracotta bricks and the finished buildings were usually sumptuous affairs with fine mosaic floors, marble-covered walls, and decorative statues.

Generally opening around lunchtime and open until dusk, baths were accessible to all, both rich and poor. In the reign of Diocletian, for example, the entrance fee was a mere two denarii - the smallest denomination of bronze coinage. Sometimes, on occasions such as public holidays, the baths were even free to enter.

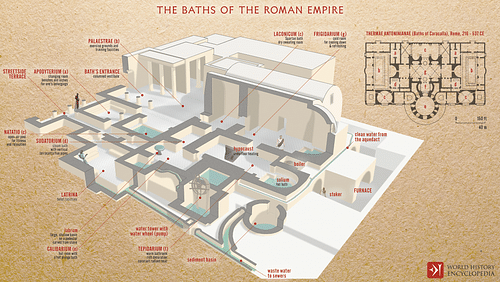

Typical Elements of Roman Baths

Typical features (listed in the probable order bathers went through) were:

- apodyterium - changing rooms.

- palaestrae - exercise rooms.

- natatio - open-air swimming pool.

- laconica and sudatoria - superheated dry and wet sweating-rooms.

- calidarium - hot room, heated and with a hot-water pool and a separate basin on a stand (labrum)

- tepidarium - warm room, indirectly heated and with a tepid pool.

- frigidarium - cool room, unheated and with a cold bath, often monumental in size and domed, it was the heart of the baths complex.

- rooms for massage and other health treatments.

Additional facilities could include cold-water plunge pools, private baths, toilets, libraries, lecture halls, fountains, and outdoor gardens.

Heating Systems

The first baths seem to have lacked a high degree of planning and were often unsightly assemblages of diverse structures. However, by the 1st century CE the baths became beautifully symmetrical and harmonious structures, often set in gardens and parks. Early baths were heated using natural hot water springs or braziers, but from the 1st century BCE more sophisticated heating systems were used such as under-floor (hypocaust) heating fuelled by wood-burning furnaces (prafurniae). This was not a new idea as Greek baths also employed such a system but, as was typical of the Romans, they took an idea and improved upon it for maximum efficiency. The huge fires from the furnaces sent warm air under the raised floor (suspensurae) which stood on narrow pillars (pilae) of solid stone, hollow cylinders, or polygonal or circular bricks. The floors were paved over with 60 cm square tiles (bipedales) which were then covered in decorative mosaics.

Walls could also provide heating with the insertion of hollow rectangular tubes (tubuli) which carried the hot air provided by the furnaces. In addition, special bricks (tegulae mammatae) had bosses at the corners of one side which trapped hot air and increased insulation against heat loss. The use of glass for windows from the 1st century CE also permitted a better regulation of temperatures and allowed the sun to add its own heat to the room.

The vast amount of water needed for the larger baths was supplied by purpose-built aqueducts and regulated by huge reservoirs in the baths complex. The reservoir of the Baths of Diocletian in Rome, for example, could hold 20,000 m³ of water. Water was heated in large lead boilers fitted over the furnaces. The water could be added (via lead pipes) to the heated water pools by using a bronze half-cylinder (testudo) connected to the boilers. Once released into the pool the hot water circulated by convection.

Outstanding Examples

Some of the more famous and splendid baths include those at Lepcis Magna (completed c. 127 CE) with their well-preserved domes, the Baths of Diocletian in Rome (completed c. 305 CE), the large bath complexes of Timgad at Ephesos, in Bath (2nd century CE), and the Antonine Baths at Carthage (c. 162 CE).

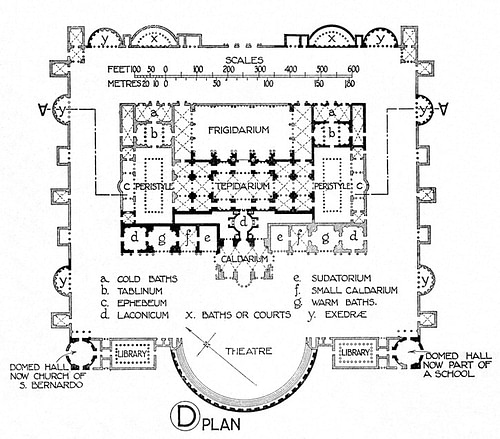

The Baths of Caracalla in the southern area of Rome are perhaps the best preserved of all Roman baths and were second only in size to Trajan's Baths of Rome (c. 110 CE). They were also the most sumptuous and luxurious Roman baths ever built. Completed in c. 235 CE, huge walls and arches still stand and attest to the imposing dimensions of the complex which used some 6.9 million bricks and had 252 interior columns. Reaching a height of up to 30 m and covering an area of 337 x 328 m, they incorporate all the classic elements one would expect, including a one-metre deep Olympic-size swimming pool and an unusual circular caldarium which reached the same height as Rome's Pantheon and spanned 36 m. The caldarium also had large glass windows to take advantage of the sun's heat and further facilities included two libraries, a watermill, and even a waterfall.

The complex had four entrances and could have accommodated as many as 8,000 daily visitors. 6,300 m³ of marble and granite lined the walls, the ceiling was decorated with glass mosaic which reflected light from the pools in an iridescent effect, there was a pair of 6 m long fountains, and the second floor provided a promenade terrace. Water was supplied by the aqua Nova Antoniniana and aqua Marcia aqueducts and local springs and stored in 18 cisterns. The baths were heated by 50 furnaces which burned ten tons of wood a day. Besides the imposing ruined walls, the site has many rooms which still contain their original marble mosaic flooring and large fragments also survive from the upper floors depicting fish scales and scenes of mythical sea creatures.

Influence on Architecture

Baths and the need to create large airy rooms with lofty ceilings brought the development of the architectural dome. The earliest surviving dome in Roman architecture is from the frigidarium of the Stabian Baths at Pompeii, which dates to the 2nd century BCE. The development of concrete in the form of stiff mortared rubble allowed unsupported walls to be built ever wider apart, as did hollow brick barrel vaults supported by buttress arches and the use of iron tie bars. These features would become widely used in other public buildings and especially in large constructions such as basilicae. Even in modern times Roman baths have continued to influence designers, for example, both the Chicago Railroad Station and the Pennsylvania Station in New York have perfectly copied the architecture of the great frigidarium of the Baths of Caracalla.