Julia Domna (160-217 CE) was a Syrian-born Roman empress during the reign of her husband, Roman emperor Septimius Severus (r. April 193 - February 211 CE). She was also the mother of the emperors Geta (r. 209-211 CE) and Caracalla (r. 198-217 CE, sole ruler 211-217 CE), whom she persuaded to accept joint rule after Severus' death, per the latter's wishes. She was a well-known figure in imperial politics, especially after the death of her husband; according to Cassius Dio, Caracalla granted Julia wide latitude to administer the empire in his stead during his extensive military campaigns. From 212 through 217 CE, while Caracalla was sole emperor after Geta's murder, Julia received petitions, presided over public receptions, and handled official correspondence, and Caracalla included her name alongside his own in his letters to the Roman Senate. The actual extent of Julia's power is disputed by Julia Langford in her book on Domna's role in Severan dynasty ideology and propaganda.

Julia was well-read and politically astute. Severus may have utilized her acumen during his rise to power in the Year of the Five Emperors (193 CE) and throughout his rule. Julia supported and consulted with artists, thinkers, and scholars in many fields, creating an influential circle at court devoted to the advancement of philosophy. She often accompanied Severus on campaign, earning her the title “Mother of the Camps” from 195 CE, though Langford argues that this was done to curry favor with the Roman army. Later the title was extended to “Mother of the Augustus, of the Camps, of the Senate, and of the Country”. One count claims that Julia was bestowed more titles than any other Roman empress.

Early Life

Julia was born at Emesa, Syria (present-day Homs) in 160 CE. Her cognomen, Domna, means “black,” and she came from the wealthy, politically connected royal family of Emesa, an important religious and trading site. Julia's ancestors had been kings in Emesa until the late 1st century CE. Her father was a high priest in the temple of the sun god El-Gabal (Latinized as Elagabalus), and her older sister, Julia Maesa, was the grandmother of two future emperors herself. Her father's uncle, Julius Agrippa, was a wealthy man who had been a senior centurion of a Roman army legion. Upon his death, he left his entire estate to Julia Domna.

Marriage & Accession to Empress

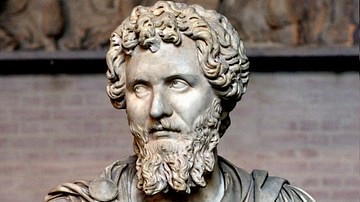

Around 180 CE, Septimius Severus, a Libyan general in the Roman army and a widower, came to Syria on the advice of an omen, which stated that Severus would find his second wife there. He met Gaius Julius Bassianus, Julia's father and high priest of the Temple of the Sun, who introduced him to his youngest, unmarried daughter. Julia Domna's horoscope had predicted that she would one day wed a king: this would have proved irresistible to the prophecy-minded Severus. The two married in 187 CE.

In 193 CE, an opportunity arose for Severus to fulfill this prophecy. The Praetorian Guard, chafing at the discipline instilled by new emperor Pertinax (r. 193 CE), assassinated him, and then auctioned off the imperial throne to the highest bidder, a senator named Julianus (r. 193 CE). The people of Rome denounced this new regime, and word spread to the provinces, where three generals, including Severus, declared themselves challengers to Julianus. Possessing superior diplomacy and propaganda skills, and positioned nearer to Rome than the others as governor of a German province, Severus marched on Rome and was recognized by the Senate as emperor, closing a sequence which is now known as the Year of the Five Emperors.

Role During Severus's Reign

After Severus's ascent to the throne in 193 CE, Julia established herself as a dynamic force in solidifying her family's imperial power. But she contended for influence with Severus' praetorian prefect, Plautianus, and at one point was forced into a trial on charges of adultery. She appears to have won the power struggle, however, as Plautianus was executed in 205 CE for plotting the overthrow of Severus's family.

Julia is also known for accompanying Severus on his imperial travels, especially on trips to the east. She was probably with him when he put down Pescennius Niger's rival claim to the throne in 194 CE, and during his subsequent Parthian campaigns, starting in 197 CE, against the vassals who had backed Niger. According to Hiesinger, many inscriptions in Syria relating to Julia can be dated to this year.

She used her position to acquaint herself with leading philosophers and artists and to promote their works and ideas. Most famously, Philostratus, a member of Julia's circle, tells a story in his Life of Apollonius of Tyana (a 1st-century CE wandering Pythagorean and sage) of how the empress commanded him to make certain enhancements to an extant work on Apollonius.

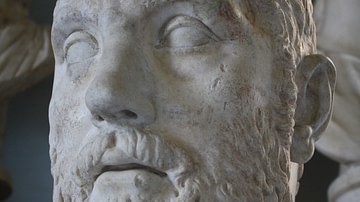

Death of Severus

Julia was in Eboracum (York) with Severus when the emperor died of an illness in 211 CE, at which time, according to his will, his sons with Julia, Caracalla and Geta, took over as joint emperors. This arrangement did not last, as there was such animosity between the two that they lived at different ends of the city. There is evidence that both Caracalla and Geta plotted against the other and that both feared for their safety. Julia attempted to mediate between her sons, and when Caracalla expressed a desire for reconciliation with Geta, Julia granted his request for a meeting with his brother in Julia's private apartments.

This was a ruse: at the meeting, Caracalla's centurions rushed Geta and stabbed him to death. According to Cassius Dio, Geta died in Julia's arms, and Julia herself was so thoroughly covered in Geta's blood that she failed to notice that she had sustained a wound to her hand in the attack. After Geta's death, Caracalla become the sole ruler of Rome, and he immediately instituted a damnatio memoriae against Geta. A later, scholarly term, literally meaning "condemnation of memory," this was a prohibition on a person from appearing in all official Roman accounts, which often included the destruction of images (as seen in the Severan Tondo shown above) and even the speaking of names. Because of this policy, it was likely unsafe for Julia to express any sorrow over her younger son Geta's death, even in private, for fear that Caracalla would also have her assassinated.

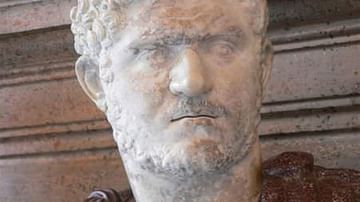

Role During Caracalla's Reign

Despite this, Caracalla entrusted Julia with much of the empire's administration while he pursued his foreign policy aims and oversaw a brutal crackdown against Geta's followers and anyone he deemed a threat. Julia carried out these duties largely from Antioch, a major Syrian city near her hometown of Emesa.

Caracalla soon after left the city on campaign, and he never returned during the remainder of his six-year reign as emperor. He was in Syria in 217 CE, not far from his mother Julia's birthplace, when his soldiers mutinied and murdered him. Upon receiving the news in Antioch, Julia attempted to starve herself to death. Her reaction was not entirely due to the loss of her eldest son, whose character she was under no illusions about, but it also sprang from a desire to avoid having to return to life as a private citizen after so many years in power.

Macrinus (r. 217-218 CE), mastermind of Caracalla's assassination and the new Roman emperor, at first made encomiums to Julia, sending her his good wishes and keeping in place her courtiers and cohort of guards. According to Dio, Julia began to envision herself as the sole ruler of Rome, and hatched a plot to usurp the imperial power from Macrinus. This did not work, as word of this plot reached Macrinus, who ordered Julia to leave Antioch.

Death

Faced again with a return to private life and likely uncertain of her security, Julia chose to give up her life, and this time carried the suicide through by means of starvation. The true circumstances of Julia's death remain uncertain, as according to Dio, Julia was also in the later stages of breast cancer by this time. In any case, soon after Caracalla's murder, Julia was herself dead at the age of 57. Her remains were initially interred in the Mausoleum of Augustus, but her sister Julia Maesa later transferred them, along with those of Caracalla and Geta, to the Mausoleum of Hadrian, which already contained Severus's ashes.

Julia Domna was deified by Elagabalus, her great-nephew and Macrinus's successor, and, according to Benario, she was actually worshipped across the empire under various local titles. Her legacy is mixed, but, as Hiesinger notes, there is no doubt that she was “one of the most powerful and active empresses in Roman history” (40).