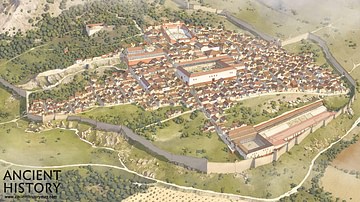

Halicarnassus (modern Bodrum, Turkey) was an ancient Ionian Greek city in the region of Caria, located on the coast of Anatolia. It is best known as the birthplace of Herodotus (l. c. 484-425/413 BCE), the 'Father of History', and as the site of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

According to tradition, it was founded by Dorian Greeks of the Peloponnese who originally settled on the island of Zephyria just off the coast. In time, Zephyria was joined to the mainland through an accumulation of silt and the people expanded their settlement throughout the area known to the Carians as Alos Karnos which was Hellenized as Halicarnassus (also given as Halikarnassos). This region had originally been home to the Mycenaean Civilization, as evidenced by the discovery of their distinctive tombs there that predate the Dorians.

The city flourished under the Lygdamid Dynasty (c. 520-450 BCE) and the Hecatomnid Dynasty (c. 395-326 BCE) - as a satrapy of the Persian Achaemenid Empire – and both dynasties played important parts in the city’s history. Under the last of the Lygdamids, in 454 BCE, Herodotus was forced to leave his home city on the travels that would inform his Histories and, under the Hecatomnids, the great Mausoleum was built by Artemisia II of Caria for her brother-husband Mausolus.

The city fell to Alexander the Great in 334 BCE after the Siege of Halicarnassus who then handed it back to the last Hecatomnid queen Ada who, in turn, bequeathed it to him in her will. After Alexander’s death, Halicarnassus was taken in turn by his warring generals until it came under the hegemony of the Ptolemaic Dynasty of Egypt which controlled it until the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BCE when it was taken by Rome.

Roman Halicarnassus continued as an important trade center and, in the early Christian era, became one of the more significant bishoprics. In 1404, the Christian Knights of St. John established the Castle of St. Peter in the area that was once ancient Zephyria, using materials taken from the ruins of the Mausoleum. The site was first professionally excavated in 1856-1857 and again in 1865 with further work continuing to the present day. The ruins of the ancient city, as well as the medieval castle, are regularly listed among the most popular tourist attractions of the region.

Early History

The Mycenaean Civilization (c. 1700-1100 BCE) had established itself in the region that became Halicarnassus by the latter period of the 15th century BCE. Over 40 of the distinctive tholos (beehive-shaped) tombs of the Mycenaeans have been found near the ruins of the ancient city. This is hardly surprising since Mycenaean trade centers were established throughout the ancient Mediterranean from the Peloponnese to Athens, the Levant, Anatolia, Cyprus, and elsewhere.

Mycenaean society and culture were influenced by the earlier Minoan civilization (2000-1450 BCE), including Minoan maritime trade. As the Minoans’ successors, the Myceneans followed the established trade routes and created new ones – including the site of future Halicarnassus. Maritime vessels such as the Uluburun shipwreck – a 14th century BCE merchant ship found off the coast of Turkey in 1982 – would have docked at the port in Anatolia to trade their goods before moving on to the next market.

At some point in the early Archaic Period (8th century - c. 480 BCE), the Dorians of the cities of Argos and Troezen on the Peloponnese settled on Zephyria and then spread to the mainland either before or after the island became joined to the coast. According to legend, they were led to the site by Anthes, a son of the sea god Poseidon, who became the city’s founder as Poseidon and Athena became its patron deities.

Sometime after its founding (though a precise date is unknown) Halicarnassus became part of the Doric Hexapolis, a federation of six Doric cities including:

- Camirus (on Rhodes)

- Cnidos (in Caria)

- Cos (on Cos or Kos)

- Halicarnassus (in Caria)

- Ialysus (on Rhodes)

- Lindos (on Rhodes)

These six allied for mutual defense and trade and celebrated their bond through a festival held on the Triopian peninsula (named after Triopas, the mythical founder of Cnidos and son of Poseidon) in honor of Triopian Apollo whose sanctuary was located there. The festival involved games with strict rules for the winners of the bronze tripod prize and these rules were always followed until a competitor from Halicarnassus decided to ignore them. Herodotus relates the story of how the Doric Hexapolis came to be the Doric Pentapolis:

The Dorians from the region now known as Five Towns (though it used to be called Six towns) …make sure that none of their Dorian neighbors are admitted into the Triopian sanctuary; indeed, they even excluded those of their own number who abused the customs of the sanctuary from making use of the place. It has long been the rule that winners in the games sacred to Triopian Apollo were awarded bronze tripods, and that the recipients of these tripods were not allowed to take them out of the sanctuary but had to dedicate them there to the god. Once, however, a man from Halicarnassus, whose name was Agasicles, disregarded the rule after his victory and took his tripod back home, where he nailed it down. For this offence, the five towns – Lindos, Ialysus, Camirus, Cos, and Cnidos – excluded the sixth town, Halicarnassus, from making use of the sanctuary. So that was the penalty imposed by the five towns on the Halicarnassians. (Book I.144/Waterfield, 65)

How this affected Halicarnassus overall is unknown but the city’s exclusion from the Doric Hexapolis most likely encouraged its later loyalty to the Persian Achaemenid Empire, unlike other Ionian and Doric Greek settlements in Anatolia.

Lygdamid Dynasty

Cyrus II (also known as Cyrus the Great, r. c. 550-530 BCE) took Caria as part of the Achaemenid Empire in 545 BCE after conquering the Kingdom of Lydia in Asia Minor in 546 BCE following the Battle of Thymbra. In keeping with Persian policy, a satrap (governor) was placed in control of the region and, in c. 520 BCE, the satrap who ruled from Halicarnassus was Lygdamis I (r. c. 520-484 BCE), founder of the Lygdamid Dynasty. Little is known of his reign except that he was of Carian-Greek descent and is almost always only referenced as the father of Artemisia I of Caria, his successor.

Artemisia I (l. 480 BCE) was made famous by Herodotus’ account of her command of Persian forces during their 480 BCE invasion of Greece under Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BCE). According to Herodotus, she distinguished herself first by counseling Xerxes I to avoid engaging the Greeks in a naval battle and then, after he ignored her advice and the Battle of Salamis was going poorly for the Persians, stood out as one of the most capable commanders (although, also according to Herodotus, this was actually for sinking a ship allied with the Persians which, since none of the crew survived, was assumed to have been Greek). She is said to have accompanied Xerxes I’s children to Ephesos after his defeat and then disappears from the historical record.

She was succeeded by her son Pisindelis (r. c. 460-454 BCE), about whom almost nothing is known except that Halicarnassus seems to have prospered under his reign, and he was succeeded by Lygdamis II (r. c. 454-450 BCE). Lygdamis II’s authority was challenged by a coalition of citizens trying to unseat him, including the poet Panyassis of Halicarnassus (d. 454 BCE) who was a relative (possibly an uncle) of Herodotus. The coup failed and Panyassis was executed. It is thought that this event turned popular opinion against the family, resulting in Herodotus’ decision to leave the city and begin his travels in 454 BCE. He recorded these travels, and various observations, in the nine books of his Histories, published between c. 430-415 BCE, which established the genre of history writing.

After Lygdamis II died in 450 BCE, Halicarnassus joined the Delian League, a federation of Greek city-states under Athenian leadership, based on the island of Delos and founded to protect Greece from another Persian invasion. After the Second Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE), the Delian League was disbanded by the victorious Spartans. In 395 BCE, Halicarnassus returned to Achaemenid Persian control under the satrap Hecatomnus (r. c. 395-377 BCE), founder of the Hecatomnid Dynasty.

Hecatomnid Dynasty

Hecatomnus was succeeded by Mausolus (r. c. 377-353 BCE) and his sister-wife Artemisia II (who succeeded him as sole ruler 353-351 BCE). The Hecatomnids married their siblings to ensure there would be no challengers to the family’s control of the throne but, it is thought, these unions were symbolic and, perhaps, were intended to convey an image of balance and stability (though this is speculative).

Mausolus was satrap of Halicarnassus during the Great Satrap Revolt of 372-362 BCE when some of the satraps, displeased with the policies of the Persian ruler Artaxerxes II Memnon (r. 404-358 BCE), rose against him with support from Egypt. Mausolus, clearly an expert diplomat, remained loyal to Artaxerxes II but played both sides for his own self-interest. Each satrapy was obligated to pay taxes to the king and, at one point, Mausolus told the rebel satraps that he was unable to pay but had been granted leniency by Artaxerxes II by promising to pay more than was owed later. He encouraged them to do the same since, even though they were in rebellion, they would not want to risk the king’s full wrath. The satraps did as he suggested and, when the time came to pay, the higher amount covered what was owed by Mausolus, who paid nothing.

Although nominally a satrap of Persia, Mausolus’ policies routinely followed this same paradigm of enriching himself and his realm at others’ expense. Another example of this from the time of the Great Satrap’s Revolt was when he told the leading citizens of Halicarnassus that he had reliable intelligence Artaxerxes II was marching in their direction and he needed emergency funds for a defensive wall. After the funds were received, he deposited them in his private account and told the people the gods had informed him the time was not auspicious for wall-building and, presumably, that Artaxerxes II had changed direction.

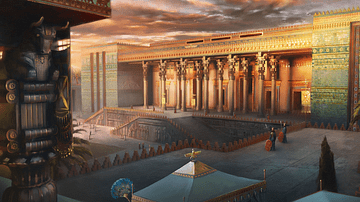

He made sure his city was well cared for, however, commissioning new roads, docks, public buildings and gardens, temples, a canal and, finally, even that wall. He seems to have been a popular ruler and, after he died (from natural causes), his wife commissioned a great tomb be built for him. Mausolus’ name is the origin of the term mausoleum from his famous tomb, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

The Roman writer Pliny the Elder (1st century CE) describes the mausoleum as a grand structure 140 feet (45 m) tall with a circumference of 440 feet (140 m), ringed by 36 columns and topped by a pyramid crowned by a statue of Mausolus-as-Hercules driving a four-horse chariot (Natural History, 36.4). Although Artemisia II commissioned the work, it was designed, at least in rough form, by Mausolus, and its construction was overseen by the architect Pythius of Priene (l. 4th century BCE), also known for his work on the Temple of Athena Polias at Priene.

Artemisia II (a title only given her in the modern era to differentiate her from Artemisia I of Caria) ruled on her own for two years after Mausolus’ death until, according to Strabo, she “wasted away and died through grief for her husband” (Geography, Book 14; 17). Work continued on the mausoleum after her death out of respect for her and her husband and it was completed c. 350 BCE. She was succeeded by her brother Idrieus (r. 351-344 BCE) and his sister-wife Ada.

After Idrieus died in 344 BCE, Ada reigned alone until 340 BCE when she was deposed by her younger brother Pixodarus (r. 340-335 BCE) who discarded the family’s tradition and married a noblewoman named Aphneis. The marriage produced a daughter, Ada (referred to as Ada II to distinguish her from her aunt) who married the Persian noble Orontobates who succeeded Pixodarus when he died in 335 BCE. Orontobates was reigning in Halicarnassus when Alexander the Great and his army appeared outside the city.

Siege of Halicarnassus

When Pixodarus seized the throne, Ada fled (or was exiled) to the inland city of Alinda with its great fortress. Alexander arrived at Alinda in 334 and was greeted warmly by Ada. Strabo provides a description of what happened next:

Ada, the daughter of Hecatomnus, whom Pixodarus had thrown out, beseeched Alexander and persuaded him to restore her to the kingdom that had been taken away from her, promising to join in helping him against the areas in revolt, for those holding them were her relatives. She also gave him Alinda, where she was living. He agreed and proclaimed her queen. When the city [Halicarnassus] except for the heights, had been taken, he gave her the siege of it. The heights were taken a little later, the siege having become a matter of anger and hatred. (Geography, Book 14;17)

Orontobates and the general Memnon of Rhodes (l. c. 380-333 BCE) had sealed the gates of the walls of Halicarnassus against Alexander. With the help of Ada, Alexander had sent envoys to the city to make contact with factions inside who objected to Orontobates’ reign and, it was hoped, would open the gates. This effort was thwarted by Memnon of Rhodes, a Greek fighting on the side of the Persians, who launched his infantry, supported by catapults on the walls, against Alexander’s waiting forces.

Alexander’s infantry was driven back but then regrouped, charged, and breached the walls. Realizing the day was lost, Orontobates and Memnon fled with their entourage and whatever could be carried to Cos after firing the city. The fire spread quickly and most of Halicarnassus was destroyed before it could be contained. Alexander handed the ruined city over to Ada who adopted him formally as her son and willed her kingdom to him. The siege and fire ended the best days of Halicarnassus which, even after it was restored, does not seem to have ever reached the heights it had known during the reign of Mausolus and Artemisia II.

Conclusion

After Alexander's death in 323 BCE, his generals fought over control of his empire in the conflict known as the Wars of the Diadochi. Halicarnassus eventually passed to his general Antigonus I (in 311 BCE) then Lysimachus (after 301 BCE) and then the Ptolemies of Egypt until 30 BCE when, after the death of the last Ptolemaic monarch, Cleopatra VII, it came under Roman rule. A series of earthquakes destroyed much of the city as well as the great mausoleum while repeated pirate attacks from the Mediterranean wreaked further havoc on the area.

By the time of the early Christian period, when Halicarnassus was an important Bishopric, there was little left of the city of Mausolus. In 1404, the Christian Knights of St. John used the ruins of the mausoleum to build their castle in Bodrum (which still exists and where one may still see the stones which once were part of a wonder of the ancient world). As noted, the ruins of the city were extensively excavated in the 19th century with work continuing in the present day. Much of its great wall, the gymnasium, a late colonnade, a temple platform, rock-cut tombs, and the site of the mausoleum (littered with those stones not used by the knights) may still be seen today and is visited annually by thousands of tourists from around the world.