On June 10, 323 BCE Alexander the Great died in Babylon. Although historians have debated the exact cause most agree that the empire he built was left without adequate leadership for there was no clear successor or heir. The military commanders who had followed the king for over a decade across the sands of Asia were left to fight each other over their small piece of the territorial pie. These were the Wars of Succession or Wars of the Diadochi. What followed were over three decades of intense rivalry. In the end three dynasties would emerge, remaining in power until the time of the Romans.

Alexander's Death

In 334 BCE Alexander and his army left Macedonia and Greece in the capable hands of Antipater I and crossed the Hellespont to conquer the Persian Empire. Now, after a decade of fighting, King Darius was dead, dying at the hands of one of his own commanders, Bessus. Although many in his army wanted to simply return home, the new, self-proclaimed king of Asia was making plans for the future. His proposed Exile Decree called for all Greek exiles to return to their native cities; however, as he sat in his tent at Babylon, trouble brewed throughout his empire. Many of his loyal troops not only protested the presence of Persians among their ranks but rebelled against his insistence that they take Persian wives. Several of the satraps - those he had put in charge to govern the occupied territories - were being executed for treason and malfeasance. After Alexander's death, other areas, even some closer to home, would seize the opportunity to revolt. Athens and Aetolia, upon hearing of the death of the king, rebelled, initiating the Lamian War (323 – 322 BCE). It took the intervention of Antipater and Craterus to force an end to it at the Battle at Crannon when the Athenian commander Leosthenes was killed.

Of course, Alexander did not live to fulfill his dreams. After a night of heavy partying, he fell ill; his health gradually deteriorated. There were those, his mother Olympias included, who claimed he had been poisoned in a supposed plot conceived by the philosopher and tutor Aristotle and Antipater, fulfilled by his sons Cassander and Iolaus. On his death bed, barely able to speak, the king handed his signet ring to his loyal commander and chiliarch (replacing Hephaestion) Perdiccas. In a scene befitting a king, he died surrounded by his commanders. Questions exist to this day concerning Alexander's final words - “to the best.” - and what they meant. Since he had not specifically named a successor, the primary concern of those closest to the king, especially his commanders, was to choose a successor.

A Search for a successor

Without Alexander, there was no government and no one had the authority to make decisions. Apparently, since he had treated his commanders equally, not wanting to create rivalry, his final words were meaningless. There was no one considered “the best.” There were, however, two likely candidates that could be considered as a possible successor. First, there was Alexander's half-brother Arrhidaeus, the son of Philip II and Philinna of Larissa. He was already in Babylon. Next, one might consider waiting until the child of Alexander's Bactrian wife Roxanne was born, but the future Alexander IV would not be born until August.

According to one historian, the struggle for leadership would be more bitter and destructive than the decade-long war against the Persians. The commanders were split: some favored Arrhidaeus, others wanted Alexander's unborn son, and then there were those who wanted to simply divide the empire among themselves. Perdiccas favored Roxanne and the future Alexander IV. For self-centered reasons, Perdiccas preferred Alexander's wife and child; he would then be able to serve as regent for the young king. Later, with Perdiccas's approval, Roxanne, favoring her son as the only true heir, chose to eliminate any competition, even if there were no children, by killing Alexander's wife Stateria, the daughter of Darius, and her sister Drypetis. To add insult she threw their bodies down a well.

Hoping to maintain a unified empire, Perdiccas brought the commanders together to decide on a successor. Many disliked the idea of waiting for the birth of Roxanne's child. Roxanne was not a pure Macedonian. One commander even suggested Alexander's four-year-old son, Heracles, by his mistress Barsine, but this idea was easily dismissed. Some looked to Arrhidaeus, and even though he was considered mentally handicapped, he was still the half-brother of Alexander and a Macedonian. The infantry commander Meleager and a number of his fellow infantry staged a revolt, choosing Arrhidaeus as the successor and even naming him Philip III. Meleager disliked Perdiccas, considering him a threat to the state. He even tried to arrest him. Seeing this as a betrayal, Perdiccas had Meleager executed in the sanctuary where he had sought refuge. The revolt was quietly suppressed. Some commanders decided to briefly put aside their differences and wait for the birth of Roxanne's child with guardians even being appointed to oversee the safety of both the child and the newly crowned Philip III. The regent Antipater would eventually have both of them brought to Macedon for safety.

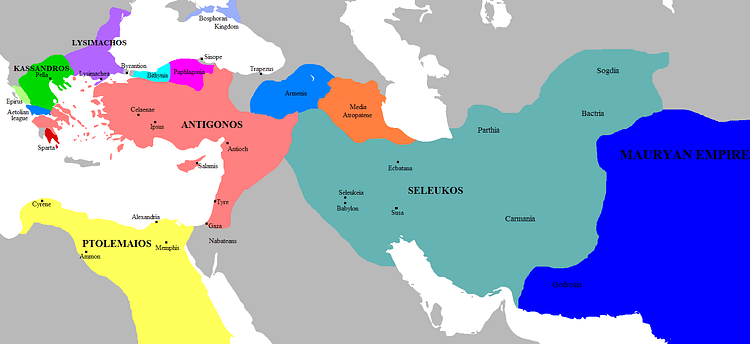

However, the death of Meleager changed the attitude of many of the commanders and set in motion the decades of war that would follow. From 323 to 281 BCE the intense competition between the commanders would escalate, as they wrestled for the control of Greece, Macedon, Asia Minor, Egypt, Central Asia, Mesopotamia and India. Although there would be brief periods of peace, the empire would never be reunited. In the end there was only one solution: the Partition of Babylon divided Alexander's kingdom among the more prominent commanders - Antipater and Craterus received Macedon and Greece, Ptolemy grabbed Egypt deposing Cleomenes, the bodyguard Lysimachus was awarded Thrace, Eumenes gained Cappadocia, and lastly, Antigonus the One-Eyed remained in Greater Phrygia.

The successor Wars

The four Successor Wars centered on the aspirations of three individuals and their descendants: Antigonus Monophthalmus I (382 - 301 BCE), Seleucus I Nicator (358 – 281 BCE) and Ptolemy I Soter (366 – 282 BCE). It would be their heirs who formed the dynasties that would exist for two more centuries. The great empire that Alexander had built extended from Macedon and Greece, eastward through Asia Minor, southward through Syria to Egypt, and eastward again through Mesopotamia and Bactria and into India. No empire like it had ever existed, and none of the successors would ever achieve anything equal to it. From Alexander's death in 323 BCE to the death of Lysimachus in 281 BCE, the old commanders fought, making and breaking numerous alliances - all with the selfish intentions of extending their own land holdings - no one could depend on another's loyalty.

With the empire divided at Babylon, the commanders made their way home. Lysimachus would have to deal with a Thracian rebellion, Antipater and Craterus fought Athens and her allies in the Lamian War, and Ptolemy had to establish himself in Egypt. The new pharaoh also had to look across the Nile and determine his next move against Perdiccas. Despite their selfish concern over land, there was one commonality among all of the commanders: no one liked Perdiccas, and Perdiccas hated Ptolemy above all others. It was very obvious from the beginning that these two men would never agree. The two had even quarreled at Babylon when Perdiccas had wanted to wait for Alexander's son to be born while Ptolemy wanted to divide the empire.

As the king's chiliarch, Perdiccas had established himself securely after Alexander's death, always hoping to reunite the empire. He had the signet ring and the king's body, preparing to return it to Macedon and a newly prepared tomb. However, at Damascus the body mysteriously disappeared - stolen by Ptolemy and taken to Memphis in Egypt. Now, with the kidnapping of the body, the long disagreement finally ended in war (322 – 321 BCE). Three failed attempts to cross the Nile into Egypt cost Perdiccas his life; he own army tired of his failure and the death of 2,000 men and killed him. Some even believe Seleucus, a one-time ally of Perdiccas, was involved. Under Alexander, Seleucus had been the commander of an elite corps of hypaspists, yet he did not acquire any territory at Babylon. Instead, he was named the commander of the Companion Cavalry. His loyalty to Ptolemy in the fight against Perdiccas, however, brought him the province of Babylonia.

The First Succesor War ( 322- 320 BCE) was all about jealousy. Before his confrontation with Ptolemy, Perdiccas had already alarmed both Antipater and Craterus in Macedon as well as Antigonus in Phrygia by his army's invasion of Asia Minor. The arguments over territory began when Perdiccas became furious at Antigonus because he refused to help Eumenes keep control of his allocated territory, Cappadocia. Eumenes was the commander of Perdiccas's forces in Asia Minor. Antigonus wanted to avoid a conflict with Perdiccas and Eumenes, so he and his son Demetrius sought refuge in Macedon. They joined forces with Antipater, Craterus, Ptolemy, and Lysimachus against Perdiccas and Eumenes. Unfortunately, Craterus died in battle when he own horse fell on him. After Perdiccas's death, Eumenes became isolated, condemned to death in the Treaty of Triparadeisus.

The Treaty of Triparadeisus

Under the guidance of Antipater, the new treaty at Triparadeisus in 321 BCE secured many of the commanders in their allotted territories. Later, when Antipater died in 319 BCE, Cassander, his son, was not named the heir to the regency of Macedon and Greece but instead was made a cavalry commander. Antipater did not believe his son was capable of defending Macedon against the other regents. In his place, Antipater appointed a commander named Polyperchon as regent. This slight would lead to a series of conflicts between the two - Cassander would ally himself with Lysimachus and Antigonus while Polyperchon would align himself with Eumenes and later the dowager queen Olympias. However, the year 319 BCE would bring an end to the first war - Perdiccas, Craterus and Antipater were dead, Seleucus was firmly established in Babylonia, Ptolemy occupied Egypt, Lysimachus sat in Thrace, and Antigonus held much of Asia Minor. The only place of discontent was in Macedon and Greece where Cassander and Polyperchon were preparing to battle.

The Second & Third Successor Wars

Over the next decade the Second Successor War (319 - 315 BCE) and Third Successor War (314 - 311 BCE) would bring about a number of dramatic changes. Cassander would roust Polyperchon from Macedon and Greece, and with the help of Antigonus establish bases at Piraeus and on the Peloponnese. And to further secure his right to sit on the Macedonian throne, he would marry the daughter of Philip II, Thessalonica. By 316 BCE at the Battle of Gabiene, Antigonus would finally be victorious against Eumenes gaining control of much of Asia- he had been ordered by Antipater at Triparadeisus to hunt down Eumenes. Eumenes would later be executed in 316 BCE after his own men betrayed him, surrendering him to Antigonus. Unfortunately, Seleucus would lose his hold on Babylonia after Antigonus's invasion, seeking refuge with Ptolemy. Luckily, he would regain his territory in 311 BCE, eventually establishing a new capital, Seleucia.

The Peace of the Dynasts was concluded in 311 BCE but quickly ended when another war, the Babylonian War (311- 309 BCE) kicked off when Seleucus invaded Babylonia with Ptolemy's support against Antigonus and his son Demetrius, regaining his lost territory at the Battle of Gaza.

In Thrace Lysimachus had been having trouble with one of the cities along the Black Sea coast. Setting his sights on the strategically important province for himself, Antigonus sent a small army to aid the city and provoke the local tribes. Finally, in 311 BCE, peace was achieved with Lysimachus remaining in control of the city, but this revolt finally drew him into the conflict that he had so long sought to avoid. He soon formed an alliance with Cassander, Ptolemy, and Seleucus.

Meanwhile, in Alexander's old homeland, Macedon, Cassander was continuing his battle against Polyperchon. Earlier, Polyperchon had fled to Epirus and aligned himself with Olympias, hoping to invade and reclaim Macedon. Cassander realized that as long as Olympias and the young Alexander IV remained alive, they would be a threat to his hold on Macedon. In 316 BCE she had ordered the assassination of her step-son Philip III - his wife Eurydice would commit suicide. In 310 BCE Cassander ordered the death of both Alexander IV and his mother Roxanne. Olympias would also die, with dignity, at the hands of his soldiers.

The Fourth Successor War

In the Fourth Successor War (308-301 BCE) Cassander and Ptolemy would continue to have troubles with Demetrius I of Macedon, “the Besieger of Cities”, when he invaded Greece and “liberated” Athens in 307 BCE from Cassander's governor. Later, in 302 BCE, he reinstituted the old League of Corinth. Meanwhile, Ptolemy had gradually been expanding northward, securing the island of Cyprus, only to lose to Demetrius at Salamis. Next, Demetrius chose to attack Rhodes but thanks to Ptolemy and his allies (Seleucus, Lysimachus, and Cassander) the siege ended in negotiations. That same year, 305 BCE, the various commanders declared themselves to be kings. By 303/302 BCE the war continued as Cassander fought to keep Demetrius and Antigonus out of Macedon. Cassander had little choice but call to his allies for help. Lysimachus moved his forces into Asia Minor causing Demetrius to abandon Greece and join his father. The Battle of Ipsus brought Lysimachus, Seleucus, and Cassander against Antigonus and Demetrius. The battle would cause not only the death of Antigonus but the end of any hope of restoring Alexander's empire. Lysimachus and Seleucus divided Antigonus's territory with the former getting lands in Asia Minor while the latter took Syria where he would ultimately build the city of Antioch.

Lysimachus Against Seleucus

Although Cassander sat securely in Macedon, his safety would not last. He died in 297 BCE leaving his homeland to the army of Demetrius who declared himself king of Macedon and Greece. The victorious Lysimachus began to expand his territory further. After the death of his old ally Cassander, he set his sights on Macedon. With the assistance of King Pyrrhus of Epirus, he crossed the border and forced Demetrius out. Demetrius and his army escaped across the Hellespont and into Asia Minor, confronting the army of Seleucus. Unfortunately for Demetrius, he was immediately captured only to die in captivity in 283 BCE, although his descendants would eventually regain Macedon and Greece.

In 282 BCE Lysimachus's one-time ally Seleucus set his sights on Lysimachus's territory in Asia Minor, and in 281 BCE the two armies met at Corupedium where Lysimachus met his death. The commander who had not received any land at Babylon and, at one point, lost what little he did gain, proved to be the true winner. Unfortunately, victory would have to be celebrated by his descendants. He would die at the hands of Ptolemy's son Ptolemy Ceraunus in 281 BCE.

The death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE had brought chaos. His failure to name a successor or heir left his commanders to eventually divide the empire among themselves. Jealousy led to over three decades of war where alliances were made and broken. The four wars of the diadochi would usher in the Hellenistic Period and bring into existence three dynasties that would exist until the time of the Romans.