Mycenaean society was strictly hierarchical, valued family lineage, and awarded higher social status to those involved with religious or military activities and palatial administration. The lower classes contained craftsmen and artisans who worked for or provided goods and services to the palaces, as well as women and slaves.

Following the excavations of Heinrich Schliemann at Mycenae in 1876, extensive research and archaeological evidence have illustrated the Mycenaeans to be a complex Late Bronze Age society that enjoyed a vivid culture of art, superior military prowess, and advanced bureaucracy. Much of what we know about Mycenaean societies comes from the analysis of tablets with Linear B script used to record administrative practices in palaces, including workshop inventories and transactions. Linear B tablets that have been translated provide key insights into Mycenaean society, including the titles and responsibilities of palatial officials, documentation of land ownership and legal disputes, the possible presence of local administrative bodies, and evidence of a private, extra-palatial social and economic sector.

First-hand, written documentation of Mycenaean societies is limited to these palatial tablets and so the scope of what is known about the Mycenaean Civilization is narrowly confined to what was recorded as being directly relevant to the palace. Though the tablets indicate social and economic activity occurring outside of the palaces' interest and control, the details of this practice, as well as of the lives of ordinary individuals, remain to be confirmed.

Mycenaean Palaces & the Origins of Aristocracy

Early Mycenaeans during the Middle Bronze Age (c. 2000- 1600 BCE) lived in simple settlements that were largely uniform throughout Greece and lacked distinct social stratification. Inhabitants of these settlements supported themselves primarily through subsistence farming and the cultivation of domesticated animal products, or by hunting. As Mycenaean society advanced towards more complex forms of government, social stratification increased and an aristocratic class of elites emerged.

By the Prepalatial Period (c. 1750-1400 BCE), broader Mycenaean civilization consisted of a network of competitive, semi-independent regional political centers. By c. 1400 BCE, the more prominent of these centers developed into functional states that operated centrally out of elaborate palaces, giving rise to what is known as the Palatial Era of Mycenaean society (c. 1400-1200 BCE). Though this evolution towards palatial administration was not uniform throughout Greece, prominent centers took hold in Mycenae, Thebes, Tiryns, Pylos, and Knossos, giving rise to an elite class of people who worked in association with the palace.

Social stratification during this period is evident by a distinct change in burial practices and the sudden inclusion of luxury items in excavated graves dated to the palatial and prepalatial periods. In early Mycenaean Greece, standard burial practice included the use of mounds, pit graves, or burying individuals below their homes. By c. 1400 BCE, it was customary for elite members of society to receive lavish burials in large tholos tombs, while ordinary individuals were buried in mounds, cist graves, or chamber tombs that were less impressive in scale. In addition to erecting monumental tombs for the Mycenaean elite, these graves are frequently found to possess luxury goods such as jewelry and ornate weapons for women and warriors, while children of the elite have been found wrapped entirely in sheet gold.

The Political Elite

Mycenaean society's most important political figure was the wanax, who presided over the palace and larger kingdom. The authority of the wanax and the related power of the palace had extensive influence over the social classes, including elites, craftsmen, and slaves. Additionally, the palace exerted control over large geographical regions, encompassing entire towns and villages. In addition to controlling palatial affairs, there is evidence of the wanax having occasional involvement with religious rituals, and as a result, the wanax is sometimes understood to be a priest-king. The wanax described in tablets from Pylos was very wealthy and was served by a documented staff of royal administrators and craftsmen. References to royal textiles imply a type of dress specific to the wanax, further indicating wealth and social superiority.

Second in rank was a figure known as the lawagetas. Linear B tablets do not provide a strict definition of the role of the lawagetas, but it is commonly suggested that they oversaw the state's army. Among the military aristocracy was a group of men referred to as heqetai, who served the wanax and are considered military-related due to their association with the use of chariots. These men are documented as owning slaves, and at Pylos, they were tasked with watching the coast to warn against potential seafaring invaders.

Mycenaean palatial states operated as complex administrative centers that employed a variety of other officials to maintain the workings of the bureaucracy. Among the elite officials involved in these economies are individuals commonly referred to as "collectors", since they are listed in the tablets by name and do not possess official titles. Individuals of this role have been identified working in a variety of industries across all the major Mycenaean states, and are thought to have been involved with acquiring and redistributing goods. The palatial workshops that produced these goods were operated by royal craftsmen and primarily focused on producing luxury goods that benefitted the elite, such as perfumes, ivory, and lapis lazuli. It is likely that literacy also extended to these additional workshop officials, who were in charge of monitoring storage. Workshop inventories were recorded on tablets by palatial scribes.

Despite the administrative control exercised by the palaces, there is also evidence of localized administration in Mycenaean Greece. In Pylos, there are thought to have been 16 different districts that were presided over by an official referred to as the koretor, whose role was similar to a modern-day governor or mayor. This figure was aided by a prokoretor, and the pair led a group of high-ranking, land-owning men known as the telestai. A third body, referred to by the term damos, is also indicated in Linear B tablets. The damos may refer in a general sense to the people of the kingdom, but it has occasionally been interpreted as a local institution, as it has been documented possessing the power to award land to individuals.

Warrior Elite

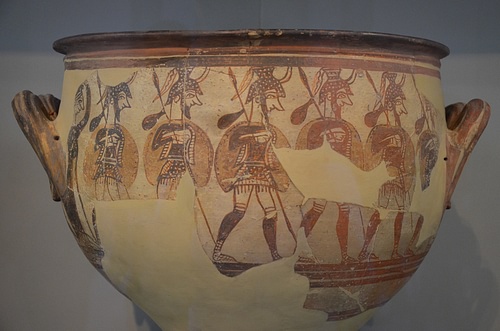

The excavated remains of Mycenaean palaces indicate the presence of fortified walls, citadels, and various frescoes documenting battle scenes and Mycenaean warfare, and this penchant for war and military achievement is a distinguishing feature of Mycenaean culture and society in the Late Bronze Age. These militaristic tendencies led to the elevation of warriors to an elite class of Mycenaeans and established a dominant culture that valued masculinity and virility, evidenced by abundant depictions of combat, weapons, and hunters in Mycenaean art.

In Mycenaean frescoes, warriors are depicted in tunics, greaves, and the iconic Mycenaean boar tusk helmets, and often carry figure eight or tower shields. Though it may seem insufficient, armor comprised of several packed layers of linen would have offered adequate protection, though metal armor was also used, as evidenced by Linear B tablets from Pylos and the Mycenaean armor known as the Dendra Panoply. However, the dress of warriors was also highly symbolic, and analysis of skeletal remains from warrior graves indicate that some elite warriors did not actually participate in battle, and instead may have engaged in duels, competing for glory and status. Elite Mycenaean warriors were valued culturally as individuals, and a particular focus was placed on the warrior's identity, glory, and beauty. Recognized not only for their skill in battle or cultural hero status, the Mycenaean warrior was also expected to maintain a distinguished appearance, and excavated graves of Mycenaean warriors frequently possess personal accessories and grooming tools.

Craftspeople & Artisans

As Mycenaean society prospered, economies became increasingly reliant on international trade, requiring a variety of skilled artisans, which served to fill out the lower classes of the social hierarchy. Typically these included smiths and armorers, perfumers, shipwrights, fullers and weavers, potters, shepherds, glassworkers, and bakers, among others. The level of palatial control over goods varied between industries, leaving room for craftspeople to operate independently. Many artisans likely provided the palace with goods voluntarily and enjoyed varying levels of social status based on the value of their trade. Additionally, craftspeople are documented in tablets as working across many industries, and although they are not given official titles, they are listed among officials, suggesting that some may have enjoyed a high social status similar to the "collectors." Infrastructure in the palaces was also fairly advanced, and highly-skilled engineers and carpenters would have been required to build the fortifications found at the sites, which included roads and bridges, tunnels for water, and infrastructure to divert rivers.

Women & Slaves

All elite officials documented in Mycenaean society were men, and the status of women was largely defined by occupation. Many Mycenaean women worked in textiles or as cult officials involved with religious and funerary rites, evidenced from painted coffins (larnakes) depicting processions of mourning women and women laying out a corpse in a ritual known as the prothesis. However, at Pylos, women designated as cult officials held titles such as priestess, key-bearer, or servant of a specific deity. These women held a higher social status, and in some instances were enabled to control land leases, had the right to challenge or engage in political and legal disputes, and were awarded plots of land by the damos. Notably, compensation for these women is not recorded by the palace, suggesting they too functioned outside of the palatial economy at Pylos.

Slaves or servants referred to as dowelos are also documented at Pylos, largely in the context of production and cult practice. While Mycenaeans slaves could also be men or children, the majority were women, likely stolen on military raids across Asia Minor. However, as servants of palatial or religious officials, many servants enjoyed a comparatively high status in Mycenaean society.