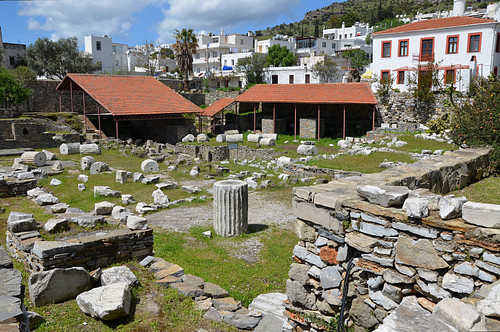

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (Bodrum, Turkey), was a massive tomb built for Mausolus, the ruler of Caria, c. 350 BCE. The marble structure was so immense and decorated with such an array of striking sculptures that it made it onto the list of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World and thereafter gave its name to any large funeral monument - a mausoleum. Following a damaging earthquake, and with many elements cannibalised for the 15th century CE Bodrum Castle, the Mausoleum no longer survives. Podium and column fragments do survive, while some substantial pieces of the Mausoleum's decorative sculpture can today be seen at the British Museum in London.

Mausolus & Halicarnassus

Mausolus (Mausolos or Mausollos) was a satrap of Persia who ruled semi-independently in Caria in modern southwest Turkey from c. 377 BCE, and Halicarnassus (or Halikarnassos) was selected as his capital c. 370 BCE. Halicarnassus was already a thriving ancient city, famous as the birthplace of the celebrated 5th-century BCE historian Herodotus and with a history dating back to the Bronze Age. Mausolus made the city even grander, adding many fine buildings including a new harbour, palace and several temples. Caria prospered thanks to Mausolus' control and development of coastal cities, which were then able to better capitalise on eastern Mediterranean trade, especially with Rhodes. The ruler's construction of a better road network to connect inland sites further improved the region's prosperity and tax revenues came flooding into the capital.

The accumulated riches in the royal coffers of Caria would be spent on one of the most lavish personal building projects ever seen in the ancient world. When Mausolos died c. 353 BCE, his body was entombed in what became known as the Maussolleion or Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. The tomb, planned by the ruler for himself and his descendants from c. 367 CE, was finished off by his sister-wife Artemisia. It was probably completed around 350 BCE, although Artemisia herself died the year before; she would be interred along with her husband and subsequent generations of their family. Conceived as a sacred monument for the city and the ruling dynasty, it was located within a large precinct right in the city's centre and connected to the agora by a large monumental staircase.

The Mausoleum

The construction of the Mausoleum was, according to the 1st-century BCE Roman architect Vitruvius in his On Architecture, supervised by the architect Pythius of Priene, and the sculptor Satyrus, who later jointly wrote a treatise on it. The structure was, like Caria itself at the time, an eclectic mix of Greek, Near Eastern, and Egyptian architectural features. It was built using Anatolian and Pentelic marble on a rectangular podium and consisted of an Ionic colonnade with a stepped pyramidal roof. On top of the roof was a massive statue of Mausolus riding a chariot in the guise of Hercules, made by Pythius himself. The 1st-century CE Roman writer Pliny the Elder gives the following description of the Mausoleum:

The circumference of this building is, in all, 440 [classical] feet [140 m], and the breadth from north to south 63 feet [20 m], the two fronts being not so wide in extent. It is twenty-five cubits in height, and is surrounded with 36 columns, the outer circumference being known as the “Pteron”…above the Pteron there is a pyramid erected, equal in height to the building below, and formed of 24 steps, which gradually taper upwards towards the summit; a platform, crowned with a representation of a four-horse chariot by Pythis. This addition makes the total height of the work 140 feet [45 m]. (Natural History, 36.4)

Modern excavations at Halicarnassus have revealed that the actual dimensions of the Mausoleum (today only fragments remain) vary slightly from Pliny's description. The high podium or base, in fact, measured 38 x 32 metres (125 x 104 ft) according to the position of the cornerstones still in situ. There is corroboration of the 36 Ionic columns and a pyramid with 24 steps. A surviving lintel stone indicates the spacing between the columns and suggests the overall dimensions of the building were 32 x 26 metres (104 x 85 ft). A 2-metre (6.5 ft) high wall once surrounded the whole mausoleum.

A surviving fragment of a chariot wheel, likely from the top sculpture, suggests the complete wheel would have been over 2 metres in diameter, making the statue some 6 metres high. The tomb itself was set within the podium and finds of sacrificial remains (oxen, sheep, lambs, and birds) suggest the building acted as the centre of a hero-cult, likely directed towards Mausolus' role as the city's re-founder c. 370 BCE. Alternatively, the remains may merely indicate a 'sending-off' feast for the dead ruler before his journey into the next life.

According to ancient writers, the famed sculptor Leochares (c. 365-325 BCE) worked on some of the decorative sculpture of the Mausoleum. Pliny the Elder agrees and also records the involvement of three other famous artists: Timotheus, Bryaxis, and Scopas. Vitruvius adds Praxiteles to the list and informs us that all of these great artists appraised each other's work to decide what would be included in the finished structure.

The Mausoleum, then, boasted many full, in the round figure sculptures carved on three different scales and painted bright colours, some of which would have stood between the columns while others stood on the steps of the podium. Fragments of various sizes have been excavated, which once belonged to 66 different statues (historians estimate there were originally at least 100). One such figure, now in the British Museum, stands 3 metres (9 ft 10 in) tall and depicts a man wearing a Greek himation mantle over a long Carian tunic. A marble frieze with relief carvings ran around the top of the podium, which had metal additions attached such as weapons and horse's reigns. This frieze, just below the colonnade, was almost one metre (39 inches) in height and included Greeks fighting Amazons (an Amazonomachy) as well as chariot racers, although these may have been part of the frieze running around the interior tomb-chamber. The frieze around the base of the roof's chariot was decorated with fighting centaurs, and large lions stood at the base of the pyramid.

The Seven Wonders

Some of the monuments of the ancient world so impressed visitors from far and wide with their beauty, artistic and architectural ambition, and sheer scale that their reputation grew as must-see (themata) sights for the ancient traveller and pilgrim. Seven such monuments became the original 'bucket list' when ancient writers such as Herodotus, Callimachus of Cyrene, Antipater of Sidon, and Philo of Byzantium compiled shortlists of the most wonderful sights of the ancient world. The Mausoleum of Halicarnassus made it onto the established list of Seven Wonders because of its audacious dimensions, rich sculptural decoration, and the many other fine buildings and artworks which surrounded it, all made by the finest artists and architects of the day. As Pausanias, the 2nd-century CE travel writer noted:

The one [tomb] at Halicarnassus was made for Mausolus, king of the city, and it is of such vast size, and so notable for all its ornament, that the Romans in their great admiration of it call remarkable tombs in their country “Mausolea.” (Description of Greece, 8.16.4)

Here, then, is perhaps the secret of the Mausoleum's success - the audacious combination of monumental architecture and gigantic sculpture solely for visual effect, commemorating not a god but a mortal. The Mausoleum, unlike many other ancient Wonders, survived more or less intact throughout antiquity, despite a few earthquakes over the centuries. The tomb likely only collapsed in the Middle Ages, perhaps in the 13th century CE.