The Battle of Thymbra (547 BCE) was the decisive engagement between Cyrus II (the Great, r. c. 550-530 BCE) of Persia and Croesus (r. 560-546 BCE), King of Lydia. The Persian victory ended the Kingdom of Lydia, which was then absorbed into the Persian empire, and enabled Cyrus to expand his territories and fully establish the Achaemenid Empire.

Croesus had arranged the marriage of his sister, Aryenis, to the king of the Medes, Astyages (r. 585-550 BCE), and maintained a cordial relationship with the Median kingdom, agreeing on the Halys River as the border between their territories. When Cyrus overthrew Astyages in c. 550 BCE, Croesus saw an opportunity to enrich himself while protecting his kingdom against possible Persian aggression and so launched a military campaign across the Halys.

An inconclusive battle was fought between the armies of Croesus and Cyrus at Pteria, and Croesus then retreated to his capital city of Sardis where he disbanded much of his army for the winter season, as was customary, and expected Cyrus to do the same. According to Xenophon (l. 430-c. 354 BCE), Cyrus was advised to follow suit by his advisers but chose instead to press on to an attack, marching on Sardis and meeting Croesus on the field of Thymbra.

Cyrus dispersed the Lydian cavalry by placing camels at the front of his army, which frightened the Lydians’ horses, and then drove his own cavalry through the breaks in the ranks, defeating Croesus and driving him back into the city. After a fourteen-day siege, Sardis fell, and Croesus was captured.

The battle is often cited as one of the most important in history as it put an end to Lydia, previously the richest and most powerful kingdom in Asia Minor, which was allied with Babylon. Once Lydia was conquered, Cyrus was able to take Babylon by 539 BCE, bringing Mesopotamia under Persian control, and founding the Achaemenid Empire.

Sources & Strengths

The main sources on the battle are the Greek writers Herodotus (l. c. 484-425/413 BCE) and Xenophon though the fall of Sardis under Croesus is also addressed by Ctesias (l. 5th century BCE). Herodotus’ account in his Histories I.79-81 and I.84 is considered accurate while Xenophon’s, from his Cyropaedia (The Education of Cyrus, 2.1.6 and 7.1.23-28) is understood as a semi-fictionalized account based on earlier works. Xenophon’s account is still recognized as reliable at points although the numbers he gives for the armies have been challenged.

According to Xenophon, Cyrus was vastly outnumbered at Thymbra, leading 200,000 men against Croesus’ army of 420,000. It is more likely that Cyrus had between 20,000-50,000 and Croesus, even though he had sent home his mercenaries, twice that number, possibly over 100,000.

The Persian army was made up primarily of Persians with mercenaries from Armenia, Arabia, and Media and included infantry, cavalry, camel cavalry (seemingly a last-minute decision on Cyrus’ part), archers, slingers, 300 war chariots, and at least five siege towers. The Lydian army consisted of Lydian cavalry as well as infantry mercenaries from Babylon, Cappadocia, Egypt, and Phrygia. Croesus also had archers, slingers, and around 300 war chariots.

Pteria & Battle of Thymbra

Croesus initiated hostilities after sending emissaries to the Oracle at Delphi asking whether he should attack Cyrus. The Oracle sent back its now-famous answer, “if he made war on the Persians, he would destroy a great empire” (Herodotus I.53). He never paused to consider that the empire that would be destroyed might be his own. Confident in his military, which had subdued the Ionian cities, he launched his attack. He seems to have been primarily motivated by the wealth of Persia he would add to his own but may also have considered his actions a preemptive strike against Cyrus to prevent an invasion of Lydia.

It is unclear whether Cyrus initially had any plans to move against Croesus’ kingdom, though he would have had to have conquered Lydia eventually in establishing his empire. He was unaware of Croesus’ campaign until he happened to hear of Lydian raids across the Halys River; there was no formal declaration given by Croesus. Cyrus would have had to assemble his army (or reassemble, as the year was drawing toward winter when troops were regularly demobilized) quickly.

However that may have been, he had a sizeable enough force to hold against Croesus at Pteria and then pursue, counting on Croesus demobilizing his forces quickly so he would not have to pay them. He even waited a few days at Pteria to allow for this before marching on Sardis. Herodotus writes:

As soon as Croesus withdrew his troops after the battle in Pteria, Cyrus learnt that he intended to disband his men. After some thought, he realized that he had better march as quickly as possible on Sardis, before the Lydian forces could gather for the second time. No sooner had he come to this decision that he put it into action and marched into Lydia. He himself was the messenger through whom Croesus heard of his arrival. This put Croesus into an impossible situation, because things had not gone according to his expectations; nevertheless, he led his troops out to battle. The Lydians were the most courageous and warlike race in Asia at the time; they fought on horseback, carried long spears, and were superb horsemen. (I.79)

Although he had thought to catch Croesus nearly defenseless, the Lydian king had been able to call back or muster a sizeable force as scholar Paul K. Davis notes:

In spite of what Cyrus had supposed, Croesus was able to call up a large army. How large is unknown, but it almost certainly was significantly more than the Persians…The two forces met just outside Sardis on the Plain of Thymbra…Cyrus placed his army in square, with flanking cavalry and chariot units set back. The Lydians deployed in the traditional formation of long parallel lines. (7)

As the Lydians advanced in an attempt to surround Cyrus’ center, he noticed breaks in their lines at the hinges which could be exploited. According to Herodotus, it was Cyrus’ general Harpagus who suggested turning the camels, who served as pack animals, into cavalry mounts and sending them first against the Lydian cavalry; the tactic credited for the Persian victory. Herodotus describes the battle:

The two sides met on the plain in front of the city of Sardis. This plain is broad and bare, with a number of rivers flowing through it, including the Hyllus. All these rivers are tributaries of the largest river, the Hermus, which rises in the mountain sacred to Mother Dindymene and issues int the sea by the town of Phocaea. When Cyrus saw the Lydians forming up for battle on this plain, he realized that the Lydian cavalry was a threat, so he adopted the following tactics, which were suggested to him by a Mede called Harpagus. There were camels with the army, used to carry food and baggage. Cyrus had them all collected and unloaded, and then he mounted men on them in full cavalry gear. Once the men were ready, he ordered them to advance against Croesus’ cavalry with the rest of the army following them – first the infantry behind the camels, and then his entire regular cavalry bringing up the rear. When all his troops had taken up their positions, he commanded them to kill every Lydian they came across without mercy, but to spare Croesus, even if he was resisting capture. These were his instructions. He had the camels positioned to confront the cavalry because horses are afraid of camels and cannot stand either their sight or their smell. In other words, the reason for the stratagem was to disable Croesus’ cavalry, which was in fact exactly the part of his army with which Croesus had intended to make a mark. So battle was joined, and as soon as the horses smelled and saw the camels, they turned tail and Croesus’ hopes were destroyed. However, this did not turn the Lydians into cowards; when they realized what was happening, they leapt off their horses and engaged the Persians on foot. Losses on both sides were heavy, but eventually the Lydians were pushed back to the city, where they were trapped behind their walls and besieged by the Persians. (I.80)

Xenophon’s account provides the same basic story but with greater detail. Xenophon had served in the Persian army and his account is fuller, and much longer, than Herodotus’. In keeping with the whole focus of his Cyropaedia, Cyrus serves as the central figure in the battle, and it is also Cyrus, not Harpagus, who comes up with the plan to use the camels. Employing the tactic of the inverted crescent, during which the front line steadily gives ground to lure the opposing army into a trap closed by the wings, Cyrus used the Lydian advance against them. In Xenophon’s account, the camels come behind Cyrus’ cavalry charge, a detail that has been challenged.

When Cyrus had completed his round of the troops, he passed on to the right wing. And Croesus, thinking that the center, which he commanded in person, was already nearer to the enemy than the wings that were spreading out beyond, gave a signal to his wings not to go out any further but to halt and face about. And when they had halted, and stood facing Cyrus’ army, Croesus gave them the signal to advance against the foe. And so the three phalanxes advanced upon the army of Cyrus, one from in front, the other two against his wings, one from the right, the other from the left; in consequence, great fear came upon all his army. For just like a little tile set inside a large one, Cyrus’ army was encompassed by the enemy on every side, except the rear, with horsemen and hoplites, with targeteers and bowmen and chariots. Still, when Cyrus gave the command, they all turned and faced the enemy. And deep silence reigned on every hand because of their apprehension as to what was coming. Then, when it seemed to Cyrus to be just the right time, he began the paean and all the army joined in the chant. After it was finished, together they raised the battle shout and, in that instant, Cyrus dashed forward; and at once he hurled his cavalry upon the enemy’s flank and in a moment, he was engaged with them hand-to-hand. With a rapid movement, the infantry followed him in good order and began to envelop the enemy on this side and on that, so that he had them at a great disadvantage; for he clashed with a phalanx against their flank; and, as a result, the enemy soon were in headlong flight.

As soon as Artagerses [Cyrus’ cavalry commander] saw Cyrus in action, he delivered his attack on the enemy’s left, putting forward the camels, as Cyrus had directed. But while the camels were still a great way off, the horses gave way before them; some took fright and ran away, others began to rear, while others plunged into one another; for such is the usual effect that camels produce upon horses. And Artagerses, with his men in order, fell upon them in their confusion; and at the same moment, the chariots also charged on both the right and the left. And many in their flight from the chariots were slain by the cavalry following up their attack upon the flank, and many also trying to escape from the cavalry were caught by the chariots. (7.1.23-28)

The Persian archers rained down arrows on the Lydian army who then took flight except for the Egyptian mercenaries who held their position until they were surrounded, and, at this point, Cyrus offered them mercy if they would join his army. The Egyptians agreed on the condition that they would not have to fight against Croesus, who had already paid them, but would serve Cyrus afterwards. Once this was agreed to, the Egyptians allowed the Persians to pass on toward Sardis and the battle was won.

Siege & Fall of Sardis

Cyrus surrounded the city while Croesus quickly sent messengers to call back his mercenaries and ask his allies for immediate assistance, as Herodotus describes:

So the Persians were besieging the city. Croesus expected the siege to last a long time, so he sent men out of the city with further dispatches for his allies. Whereas the men he had sent before had taken messages requesting the allies to gather in Sardis in four months’ time, this current lot of messengers were to ask them to come and help as quickly as possible, since he was under siege. (I.81)

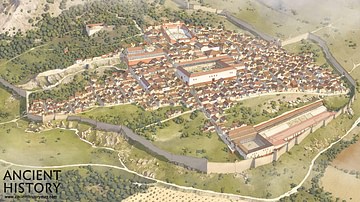

The siege went on for 14 days. Croesus received no word from his allies and Cyrus could not gain a foothold to take the city whose walls were thick and heavily fortified. Sardis was located below Mount Tmolus on which its acropolis was built, so even if the walls of the city were breached, defenders could fall back and hold the high ground. Herodotus describes how Cyrus was finally able to neutralize this advantage:

This is how Sardis fell. On the fourteenth day of the siege, Cyrus sent riders to the various contingents of his army and announced that there would be a reward for the first man to scale the wall. This induced his men to try, but without success. Then, when everyone else had given up, a Mardian called Hyroeades went up to have a go at a particular part of the acropolis where no guard had been posted, because of the steepness and unassailability of the acropolis at that spot had led people to believe that there was no danger of its ever being taken there. Even Meles, the past king of Sardis, had omitted this spot when he was carrying around the acropolis the lion to which his concubine had given birth, in response to the Telmessian judgement that Sardis would never be captured if the lion was carried around the walls. Meles carried it around the rest of the wall, where the acropolis was open to attack, but he ignored this place because of its unassailability and steepness. It is on the side of the city which faces Tmolus. Anyway, this Mardian, Hyroeades, had the day before seen a Lydian climb down this part of the acropolis after his helmet (which had rolled down the slope) and retrieve it. He noted this and thought about it, then he led a band of Persians in the ascent. Soon, a lot of them had climbed up, and then Sardis was captured and the whole city was sacked. (I.84)

Conclusion

Croesus was captured and delivered to Cyrus in chains. He was condemned to be executed along with some noble Lydian youths on a pyre but, as he stood with them, he remembered the words of the sage Solon, who had visited him when he believed himself to be the happiest man in the world. Solon had told him how no one can be counted as the happiest or most fortunate until their end is known and now, facing his execution, Croesus called out Solon’s name, recognizing he was right.

Cyrus sent interpreters to find out what Croesus was saying, and he explained Solon’s visit and its meaning which the interpreters relayed to Cyrus. Herodotus writes:

When the translators relayed the story to Cyrus, he had a change of heart. He saw that he was burning alive a fellow human being, one who had been just as well off as he was; also, he was afraid of retribution, and reflected on the total lack of certainty in human life. So he told his men to waste no time in dousing the flames and getting Croesus and the others down from the pyre. (I.86)

Herodotus then relates how the fire was put out by a sudden rainstorm he attributes to the god Apollo and how Croesus is given a position as adviser to Cyrus. This conclusion to Croesus’ story is considered unlikely and it is far more probable he was executed after the fall of Sardis.

In taking Lydia, one of the greatest threats to Cyrus’ plans of conquest was neutralized and he moved on to subdue Elam in 540 BCE and Babylon in 539 BCE, establishing the Achaemenid Empire which would eventually stretch from Asia Minor to the borders of India.